The last perfect game in Major League Baseball was thrown by Félix Hernández, on August 15th, 2012. Barack Obama was the president of the United States, and Mitt Romney was vying to become the next one. The top grossing film was The Avengers, but the first one, not the second or third or fourth or fifth or like, whatever the new one is that’s coming out tomorrow. Children who were not yet born are right now, as you read this, learning about addition and subtraction in first grade.

If one thing has been subtracted in the years since–Major League Baseball pitchers throwing perfect games–something that has been added is years on the careers of the players on the field that day. First is Félix himself, a pitcher who at the time may have been one of the three best in the entire game. Now he is 33 year-old fifth option on a rebuilding team. It might not be “over,” in the sense that we usually call careers over, but something certainly is.

Dustin Ackley manned second base for the Mariners that afternoon. Once the greatest college hitter in the nation and the second pick in the draft, Ackley is currently out of a job, as is former catching prospect Jesús Montero. Michael Saunders is too, a long fall from a career as a reliably competent member of the M’s outfield crew during those lean early 2010 years. John Jaso, who caught the game, retired in 2017, and Kyle Seager, who has been manning third base ever since, is starting to pick up dings and nicks in a body that time keeps pulling in the wrong direction. Were this just Seager’s body illustrating this oldest of metaphysical problems it would be one thing: for the only thing making any of this interesting is the fact that someone, somehow, has yet to throw another one of these. Time moves like a river, someone once said, but I’m not sure that is exactly right. Most days it feels like a photograph–a vivid one, not sunburnt with wear and age–displaying bodies with fewer lines and scars that look very little like the ones doing the looking years later.

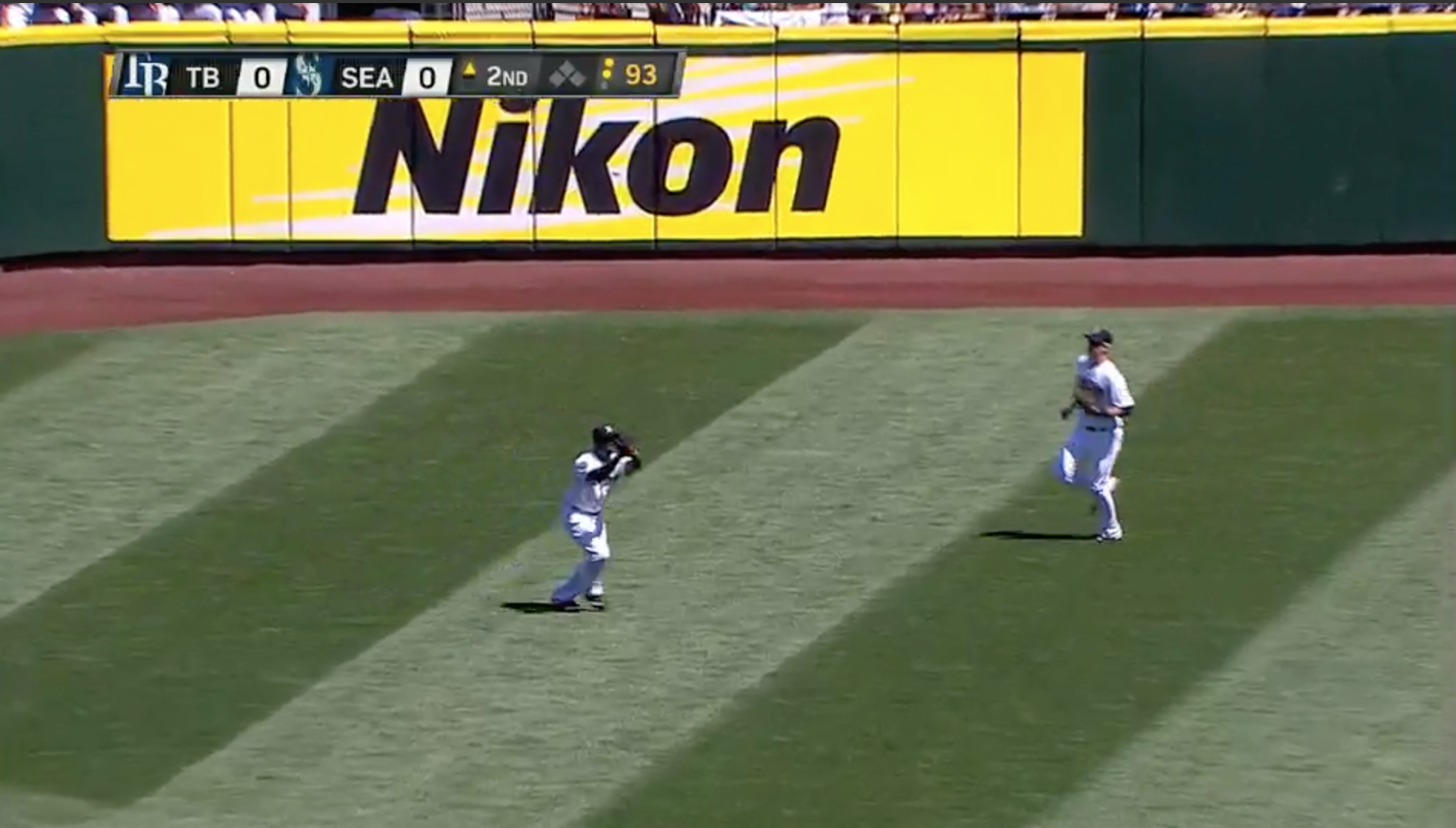

In left field for the Seattle Mariners that afternoon was a young player named Trayvon Robinson. It was his second season in the bigs, and he was seeing consistent if not regular at-bats on a team that had no illusions they would be doing anything in October in a place named something besides Cancun. In the second inning, Rays’ first baseman Carlos Peña popped up a fly ball into left field, where it caught the eye of Robinson who quickly moved in for the catch. Ever the showman, he let it drop down past his head just a little bit, catching it at eye level as if to say this is both easy and also something that everyone watching up there in the stands can only dream of being able to do.

Thirty-four games later, Robinson was out of a big league job. But yesterday, word came down that Robinson, still playing baseball seven years later and outlasting Ackley, Saunders, and Montero, might be wearing Pirates yellow in the coming days. The story of his journey back would be wasted here when the linked piece does a better telling, but I can’t help feel that for once, for once in someone’s life, in our lives, against the rules of the universe and physics as we know it, that time has been defeated, that this photograph indexing the past also provides an index of the future, something like a memory deferred.

Trayvon Robinson, evidence that memory need not be merely a temporal story about history but also, perhaps, the present, and all that will come after.

According to Robert Kaster, the ideal ancient Roman male had integritas. This isn’t the same as our modern concept of integrity, an inward quality of self. In the ancient Roman context, integritas was an outward-facing quality that shielded a man from doing anything that would attract indignation or shame. It was his ability to manage the social life of his emotions. This isn’t, for example, a matter of Bruce Banner controlling his anger because he doesn’t like being angry. This is a matter of Banner controlling how his anger plays out. If The Hulk attracts praise, then Banner is using integritas. If The Hulk attracts condemnation, then Banner is not. The key does not lie in how Banner himself feels about his anger, but how that anger plays out socially.

According to Kaster, the Roman male had to concern himself with five major emotions: verecundia (respect, shame); pudor (decency, shame, embarrassment); paenitentia (regret); invidia (envy or indignation); and fastidium (disgust). These emotions were very different from our own. We inwardly feel our emotions; by contrast, to be a Roman male demanded being hip to the situation. A man was the object of emotion, and he directed emotion at others. Emotions were like reputation currency. They functioned as social restraints. They were the unwritten rules.

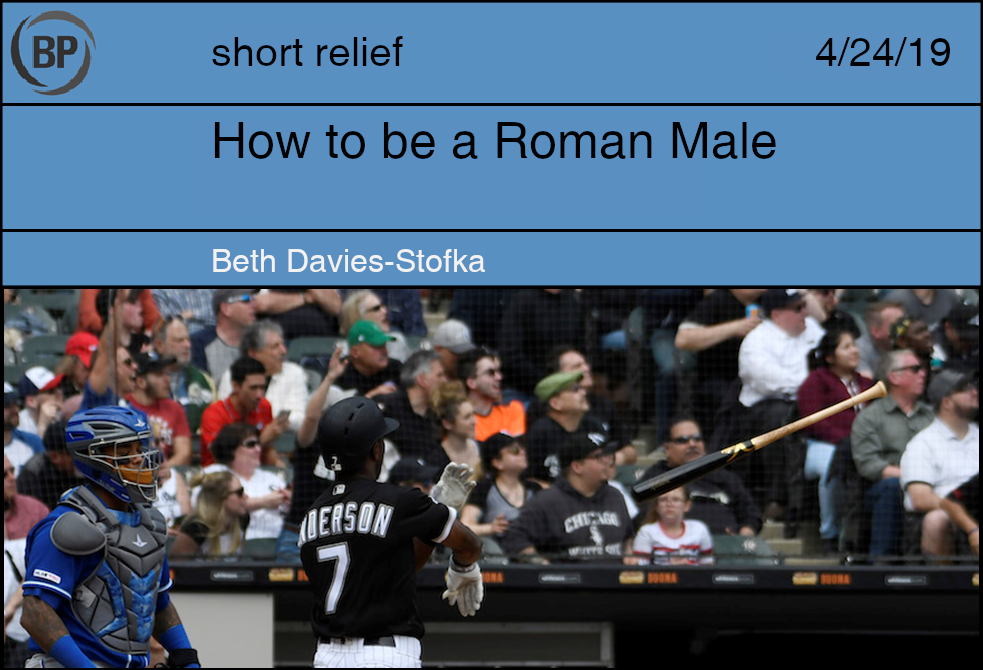

Take, for example, the bat flip. Verecundia is “the art of knowing your proper place” (15). It is “not being invisible, quite,” (17) but rather doing the minimum possible without drawing undue attention. When you hit a home run, you should put your head down and run the bases. Flip the bat, and you’ll be shamed. You’ll mismanage pudor. Pudor is “being aware of others being aware of you” (28-29). People understand that you want credit for what you’ve accomplished, but they’ll just as quickly discredit you. You have to know the situation. It wasn’t a walk-off? Don’t flip the bat.

If you do flip the bat, then brace for paenitentia, because you will know the onslaught of invidia and fastidium. These two are nasty. Invidia says, “I am so angry about that bat flip that I am going to launch a campaign against you and all bat-flippers.” Kaster (103) says that invidia can lead to divisions and discord, setting one person or faction against the other. Or, like fastidium, it can attempt “to unify a group of ‘right thinkers’…mobilized to isolate and bring shame to a highhanded renegade” (103). Invidia can lead to getting a ball thrown at you; fastidium can lead to a Twitter uproar that spills into talk shows and televised speeches.

Over a bat flip? Men of ancient Rome played a complicated game in which they managed each other’s emotions in order to protect themselves from social hostility. Baseball’s unwritten rules are eerily similar. If you flip a bat at that, then thank you. We fans need a change from the taedium.

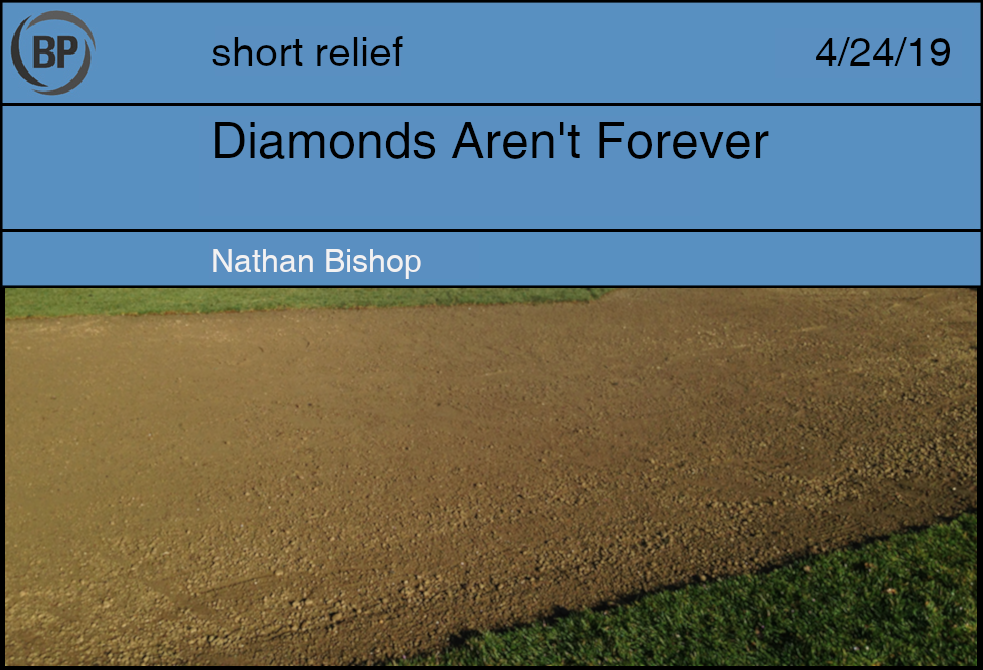

There was a field we practiced on as kids near my home. The father of one of my teammates had gone full Ray Kinsella, cleared and mowed a patch of his acreage, and plopped a full baseball field right next to his house. The outfield was small, and the crabgrass grew just thick enough to hide a few ankle-spraining holes. The infield, though, featured pristine, 90-foot basepaths, a 60-feet-six-inches-pitcher’s mound sistine chapel. My teammate was an infielder, and while his dad made him practice at all hours of all days, he ensured he did so on a diamond cut and shaped cleaner and more professionally than the local high school’s. It was an unnecessary extravagance, but it was a beautiful place to play baseball.

I stopped playing after high school, but my teammate didn’t. He went off to play at college, and ended up doing so well he got drafted in the middle rounds. He did so well in the minors he got called up to the majors, where he somehow stuck around for thirteen major league seasons. The guy I could outrun and outhit as a kid stuck it out with big leaguers for almost a decade and a half. His rookie year he hit a grand slam. I still have the newspaper lying around somewhere.

Years later, after my teammate retired and moved to Arizona, his father, that crazy old Kinsella-clone, passed away, and the family house was put up for sale. I work in real estate (like many ex-baseball players) and went to go take a look. The field was gone. The grass was thigh high, and the backstop long since removed for a collection of garden beds, topped by a small greenhouse. There was no sign a baseball field had ever been there. Time, neglect, and changing priorities had removed it from existence.

I drove home, and turned on a game, not caring who was playing or where. I just wanted to see the field; the green, the brown, the pleasing way the hard, uniform geometry of the infield gives way to the soft curves and artistic impulses of the outfield dimensions. I sat and I watched for a bit, and then the phone rang. I turned off the TV, and the field was gone.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now