As Patrick Dubuque taught us last week, every man has a breaking point. I’ve seen it many times. Most recently, I saw it this past weekend. What you are witnessing in the above image from Saturday night’s loss to the Twins is Trevor Bauer’s.

Slack-jawed, dumbfounded, and perplexed, he is wondering just how in the hell he is supposed to retire one Max Kepler, who has hit five home runs in his last five at bats off of Bauer. The Übermensch is real, he thinks, and he plays for the Minnesota Twins.

For perhaps the first time in his career, Trevor Bauer is baffled. As a pitcher for the Cleveland baseball franchise, the celebrated right-hander flummoxes batters with his fastball, knuckle-curve, slider, and cutter. He projects arrogance and self-assurance, to the point where his abrasiveness and trolling have, on more than one occasion, offended teams, teammates, and fans alike. But, sure that his actions were right, he has never truly apologized for anything. And because he has been Cleveland’s rock, along with Shane Bieber, in an ocean of injuries, he has not needed to.

Suddenly, all of that is thrown into doubt. He is standing exposed and raw like a nerve. He feels everything and nothing all at once. He is sure that everyone sees right through him. He burrows past the man who says he isn’t angry – and is, in fact, laughing – all the way through to the little boy inside who still wants people to like him, and can’t figure out why no one does. For if he cannot tame Max Kepler’s fury, how can anyone truly love him? How can he love himself?

The good news, Trevor, is that now you are ready. You have stared into the abyss, and the abyss has stared back and taunted you, like Judge Smails.

What will you do now, Trevor? Will you jump or will you turn away, salvage what’s left of your dignity and proffer your best to Jorge Polanco? It doesn’t get any easier from here, but with each pitch you lay a brick on a new path toward enlightenment. Toward being made whole. You might never reach your destination, but the journey will still be worth it should you decide to start. Will you? What do you say, hmm?

Well? We’re waiting…

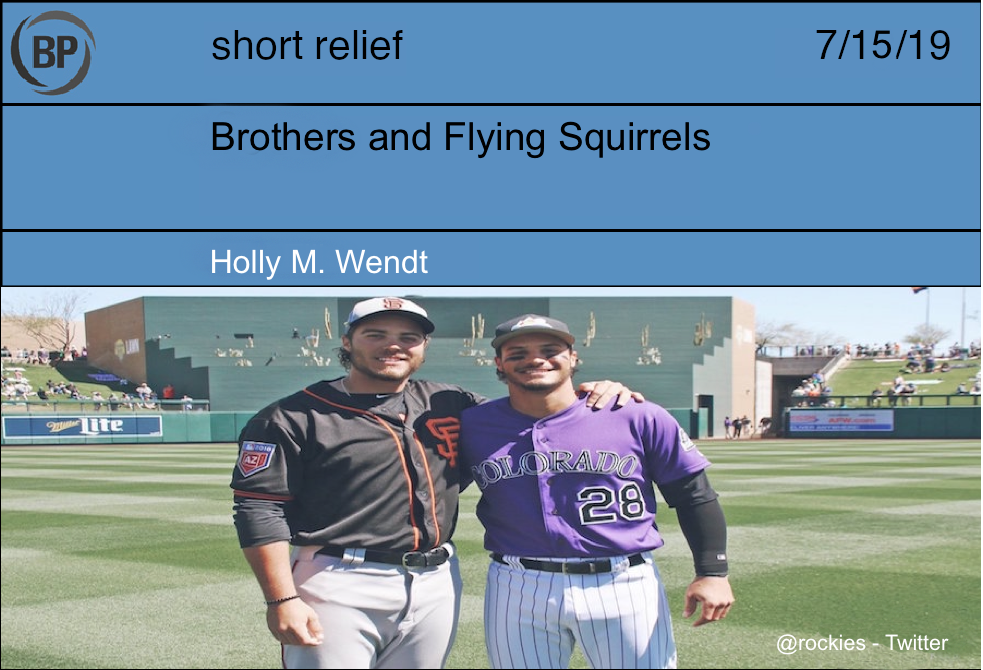

On July 6th, I followed the Double-A affiliate of the City of Brotherly Love south to take in a new stadium with an old friend. Under the promotional auspices of 90s Night and some fireworks on a holiday weekend, the Philadelphia-adjacent Reading Fightin Phils faced the Giants’ Richmond Flying Squirrels. While I didn’t get to see Reading stand-out Alec Bohm or former first-round pick Mickey Moniak, I did get to see Grenny Cumana hit a grand slam. But the players I kept thinking about were on the Richmond side: Jacob Heyward and Jonah Arenado.

Jacob Heyward is indeed the brother of Jason Heyward, and Jonah Arenado is indeed the brother of Nolan Arenado. Both play the field as their older brothers do: Jacob Heyward, as a less efficacious fielder than Jason, plays more left field than anything, but he’s certainly an outfielder, and while Jonah Arenado has seen some time at first base and taken the occasional foray at shortstop, he’s most often found at the hot corner. Both Jacob and Jonah are currently older than their brothers were when they made their MLB debuts; both were selected quite a lot deeper into the MLB draft. But both are also still younger than the average competitor in Double-A. Both had solid enough nights for their team—Heyward with a walk and a single, Arenado with a lot of skill and success on defense on a night when the ball just kept finding him. Both are still better—exponentially better—at baseball than the vast majority of the population.

When thinking about this quartet of players I don’t know, I remind myself: each person has their strengths, their qualities. Life itself is neither a race nor a game. It’s not about competition, about comparison.

Unless of course, you are a person who has a brother, especially an older brother who is definitively better than you are at sports. Then it absolutely is a competition, and you are always losing.

I am, obviously, one of those people. My older brother is a foot taller than I am, sharp as a shadow, one of those people who can do useful things with both hands, one of those people who can stunt and feint and perform sleight of hand with a baseball without anyone ever having seen them practice the trick. Once he hit high school, I really don’t remember seeing him practice anything. I do remember the baseball flinging fast from his fingertips, the ropey liners leaping from his bat to show how clearly he could see the ball. How I couldn’t. I remember him spending January Saturdays and all the nights of the offseason doing whatever he wanted—the same days and nights I spent at softball clinics at local colleges, at open gyms: all that time I spent not even scratching the surface of those skills with which he seemed born.

Even last month, while my brother celebrated his fortieth birthday at my house, where the whole family was playing ping-pong, a game none of us have played since the mid-nineties, he was doing those things again. He tried to avoid playing altogether, tried evading on account of a balky back and general stubbornness, but then he picked up a paddle and faked me right out of my shoes. He turned his whole head to the wall and served up treacherous backspin; he switched hands and played behind his back and almost thirty years fell away. And he was still too much fun to watch for me to feel mad about it.

January, 2019. Turrialba, Costa Rica. A factory. Employees are stitching baseballs expertly, except EMPLOYEE 1, whose workstation is a wasteland of leather and red yarn.

[EMPLOYEE 1 leans over to EMPLOYEE 2 and whispers conspiratorially.]

EMPLOYEE 1: What do you say we…juice up some of these balls?

EMPLOYEE 2: You’ve got to stop suggesting that.

EMPLOYEE 1: How about: I stop suggesting…when you start juicing.

EMPLOYEE 2: I don’t even know what that means. It’s not sexual, right? Please tell me it’s not sexual.

EMPLOYEE 1: What? Oh! Sorry, I see how you’d think that. No, it means making them travel farther.

EMPLOYEE 2: Travel farther?

EMPLOYEE 1: When they’re hit.

EMPLOYEE 2: Hit with what? And who are you? You obviously don’t work here.

EMPLOYEE 1: Of, uh, of course I work here. Why would you say such a silly thing, worker?

EMPLOYEE 2: Well, you keep addressing me as, “worker.” Your fake mustache keeps falling off, you clearly don’t know how to stitch a baseball, my boss keeps stopping by and asking, “Can I get you another espresso, Mr. Manfred?” Stuff like that.

EMPLOYEE 1: Who, Kenny?

EMPLOYEE 2: Yes, Kenny, known to us workers—who work here—as Mr. West.

EMPLOYEE 1: Kenny’s a sweetheart. He doesn’t fetch espresso for you as well, worker?

[EMPLOYEE 1’s mustache falls into a pile of yarn. He hastily disentangles it and reapplies it to his face.]

EMPLOYEE 2: He does not.

EMPLOYEE 1: Well I can’t divulge my identity—

EMPLOYEE 2: Of course not, Mr. Manfred.

EMPLOYEE 1: —But I can promise that Mr., uh…Mr. Kenny would fetch all the espresso you desire, if you helped me juice these baseballs.

EMPLOYEE 2: Which entails making them travel farther when you hit them with something?

EMPLOYEE 1: Yes! They’ll fly farther off the bat! More home runs? More excitement? Ratings up. No jeremiads about the state of the game. The crowd goes wild! Dingers galore! Chicks dig the long ball!

EMPLOYEE 2: Are you sure this isn’t sexual?

EMPLOYEE 1: [Shouting] IT’S NOT SEXUAL!

[All heads turn toward EMPLOYEE 1.]

EMPLOYEE 1: [Whispering] It’s not sexual.

BOSS: [Hesitantly] Everything ok, Mr. Manfred, sir?

EMPLOYEE 1: All good, Kenny. Could I maybe get another espresso?

BOSS: [Sprinting out] Yes, sir, Mr. Manfred, sir!

EMPLOYEE 1: Just help me make more home runs.

EMPLOYEE 2: And what’s a home run? Is that a baseball thing?

EMPLOYEE 1: Of course! You mean to—you don’t know baseball? You don’t like baseball?

EMPLOYEE 2: I tried, man. I watched a game once. First thing I saw? That guy in the middle, on the dirty hill—

EMPLOYEE 1: The pitcher?

EMPLOYEE 2: Sure, the pitcher, first thing he does, he licks his fingers—which, gross—then he grabs a handful of dirt, and starts rubbing it all over the ball. That. I. Made. The disrespect! Do you know how long it takes me to make a ball?

EMPLOYEE 1: Honestly, I have no idea how anything works here.

EMPLOYEE 2: Yeah, the last ball you made looked like Forky from Toy Story 4.

EMPLOYEE 1: Like what?

EMPLOYEE 2: It’s a movie that won’t be released for another six months, don’t worry about it.

EMPLOYEE 1: Oh, I love movies.

EMPLOYEE 2: The point is, baseball is garbage. And I will get that…pitcher? I’ll get him back. They announced his name right after he desecrated my life’s work, and I will never forget it. One day I will destroy you, Justin Verlander.

EMPLOYEE 1: Verlander, you say?

EMPLOYEE 2: Justin Verlander. Doesn’t it just sound like another name for the devil?

EMPLOYEE 1: What if I told you that juicing the balls would get you even with Justin Verlander?

EMPLOYEE 2: Well, I might not believe you, since pretty much everything you’ve said is a lie…

[EMPLOYEE 1’s mustache falls directly into a tiny espresso mug on his workstation. He frenziedly dries it on his shirt and reapplies it.]

EMPLOYEE 2: But sure, what the hell. What did you have in mind? [Starts sketching on a piece of paper.] Smoother seams and leather to reduce drag? A denser core would increase the coefficient of restitution.

EMPLOYEE 1: Those, um, that sounds—I’m a little—these, these are scientific terms?

EMPLOYEE 2: I can juice the ball.

EMPLOYEE 1: You can juice it?

EMPLOYEE 2: I can juice it.

BOSS: [Sprinting in, out of breath]: Here’s that espresso, Mr. Manfred!

EMPLOYEE 1: Thank you, Kenny. And could you please fetch another for my friend here?

EMPLOYEE 2: I’ll see you in hell, Justin Verlander.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now