Most of the universe complained Friday night when Dodgers manager Dave Roberts removed left-hander Clayton Kershaw three outs from a shutout against the Braves in Game 2 of the NLDS. How could Roberts do this in front of Sandy Koufax? This tweet, fired off right after Roberts fooled everyone into believing he would leave Kershaw alone, probably sums up the community distaste:

Fan unhappiness was understandable; to say that pitching deep into games has become a lost art is understating it. Heck, some MLB managers don’t even bother with the pretense of having a starting pitcher; relievers start games now, fully intending to go an inning or two as a bridge to a bridge to a bridge to the closer. Kershaw potentially going nine in a playoff game represented a deeper pining for a bygone tactic. But more than that, it was a little personal. Kershaw’s age-30 season, while certainly very good, continued a few concerning career trends. He spent more time on the disabled list, he posted his highest ERA since 2010 and lowest strikeout percentage since he was 20 years old. He didn’t make the All-Star team. He won only nine games. (Pitcher wins are for saps, sure, but 21-3 always looks better.)

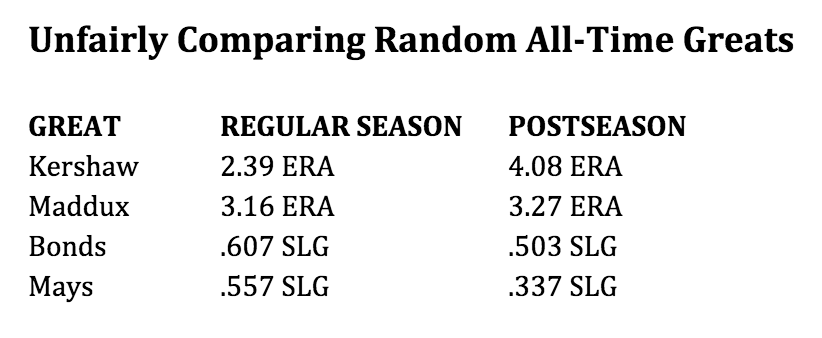

Not only was Kershaw three outs from finishing the finest postseason appearance of his career but also, having logged just 85 pitches, he was in position for a Postseason Maddux—a complete-game shutout needing fewer than 100 pitches. Not even Greg Maddux ever threw a Maddux in the playoffs! One of the all-time greats couldn’t even live up to himself in the playoffs—how about that?

Kershaw’s own playoff history is a frustrating narrative to be sure. There’s this cloud that appears every time he starts, nagging some into thinking Kershaw is a postseason choker. Kershaw in the playoffs not only comes under criticism, but he’s also pitied. (I even made fun of it, noting that Matt Adams wasn’t there to bother Kershaw anymore. We’re all terrible people, starting with myself!)

As far as individual games, Kershaw’s had some doozies, notably Game 1 of the 2014 NLDS against the Cardinals, when an eight-run seventh inning erased a four-run lead. Other moments have been no less disappointing, but pitchers as a class are discriminated against. An All-Star slugger taking the collar will happen once in a while, but God forbid you’re a pitcher who has a crap game. Maddux delivered some stinkers in the postseason, too, but he also got protected from criticism relatively early by pitching for a World Series winner in 1995. That forgives a lot of playoff sins.

While it’s true that Kershaw’s career 4.08 ERA in 25 postseason appearances (20 starts) is something more suitable for James Shields at his best, his aggregate numbers have been improving ever since that particularly bad start against the Cards. The Dodgers have won 10 of Kershaw’s past 12 playoff starts. And that’s what you want from Kershaw. Until he pitches for a World Series winner, and maybe even after that, there are always going to be people who don’t think Kershaw is good enough.

What else is funny about the Kershaw criticisms isn’t an association with Maddux, whose own postseason numbers paled when compared to his regular-season dominance, but instead how the narratives are so much like what Barry Bonds used to hear. Until the Giants made a run to Game 7 of the 2002 World Series thanks in large part to Bonds going on an unholy tear that paralleled his charge on the all-time home run record, Bonds was considered a big-game choker.

Bonds the slugger didn’t simply take the collar once in a while in the playoffs. He wore it like fashion. Through his age-36 season, Bonds was a .196/.319/.299 hitter with one homer and six RBIs in 27 career playoff games. And he got off to a start that wasn’t even that good.

From 1990-1992, the Pirates went a collective 8-12 with Bonds in the playoffs during that span, never able to beat the Reds or Braves and reach the World Series. Bonds hit a measly .191 in 83 plate appearances and, although he was able to draw 14 walks (one intentional) and steal six bases, he slugged .265, hitting one home run and two doubles. It was bad. The image of Bonds being unable to throw out Sid Bream at the plate didn’t help, either.

Bonds’ results weren’t much better in his next wave of playoff appearances with the Giants in 1997 and 2000. No home runs, only three walks in seven games combined, a paltry slash line overall, and a 1-6 team record with no advancement past the Marlins and Mets.

Then came 2002, and the past was forgotten. All told, Bonds finished with a slash line of .245/.433/.503 with nine homers in 208 plate appearances for his playoff career. His teams went 20-28. Not the ideal Bonds, but much better by the end than at the start. It’s almost like six games, or 13 games, or 20 games, or even 23 games isn’t enough of a sample to draw any conclusions.

Willie Mays, speaking of connections to Bonds, probably is considered by a plurality to be the best player of all time. He hit .247/.323/.337 in 99 postseason plate appearances. His teams won two postseason series. And when it comes to Mays’ legacy, basically nobody cares—aside for some pity due to the lasting images of his anguish during the 1973 World Series. No matter, everyone knows how good Willie Mays was.

And that’s how it should be with Kershaw. Not only was he pitching against the Braves, himself, Dave Roberts, the world, Greg Maddux, and Barry Bonds, but Willie Mays too! No fair. That’s why everyone (aside from Braves fans, possibly) wanted to watch Kershaw finish the game. We wanted the image burned into our brains of him being there at the end, dominating in true Kershaw fashion. As for the overall stat line, give the guy enough postseason opportunities and his numbers will be (closer to) where they should. He’s working on it. For now, please clap:

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now