Things are getting progressively worse at the plate for Reds center fielder Billy Hamilton. The chosen one of the speed-only profile, if such a thing ever existed, he’s tumbling further and further into offensive ineptitude, slashing a cringe-worthy .197/.285/.282 from the ninth spot in the batting order. The things at which Hamilton is good–defense and baserunning–continue to raise the question of how he could be best utilized, but we’re here to examine a part of the game that’s conspicuously and perplexingly absent from his strengths: Bunting.

Since 2000, 103 players have bunted in 50 or more at-bats (read: non-sacrifices). Hamilton’s .347 batting average on bunts ranks 96th. Baseball as a whole has hit between .390 to .405 on bunts in each season of the 2010s.

We’ve collectively spent a lot of time considering whether to bunt, who should bunt, when to bunt. Plus my personal favorite: When not to bunt. Once in motion, though, bunting feels like the rare baseball decision where an instant judgment–that couch isn’t fitting through that door–doesn’t need the usual confirmation from the measuring tape that is data.

We don’t spend much time asking how to bunt. Unwittingly, I started asking that question to discern why Hamilton hasn’t found even average success in this speed-based pursuit. I figured the underlying currents of the bunt had been harnessed, that the forces at work would be apparent. I thought bunts would generally be deployed as the numbers suggested they should.

I was wrong.

***

Before we dive into the deep, dizzying array of tables and averages and such, I want you to remember where you started. There are, to my mind, three basic factors involved in whether the person who turns the bat from weapon to shield achieves the goal of reaching first base.

- Which way does the bunt go?

- Who is called on to field and throw the ball?

- How fast can the hitter reach first base?

The ideal or optimal answers to these questions can end up counteracting one another. In a vacuum, bunts down the third-base line force longer, more difficult throws and eliminate the chance of a tag. However, the superior defender plays that side and often has fewer other obligations to attend to, such as covering first base. There’s also the option of bunting straight ahead, but the pitcher and/or catcher end up extremely close to the ball in those cases. Plenty of left-handed hitters, Hamilton included, sometimes attempt running starts with their bunts. That doesn’t make going to the third-base side impossible, but more difficult? Sure.

Then there’s the circumstance of speediness that looms over every bunt for Hamilton (or Dee Gordon or Byron Buxton or any number of players). It brings the third baseman even closer. It might make the pitches more difficult to get down. It might even make the pitcher and catcher better defenders simply because they are on alert. Who knows.

So, think of how you’d bunt. Think of how you’d bunt when most everyone in the ballpark knows you’re at least considering a bunt. Got it?

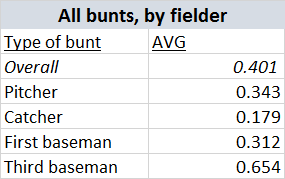

Now, the wisdom of the crowd of bunts in the majors, the wisdom of an old Baseball Info Solutions study, and the wisdom of recent results all point toward third base in big, green, flashing arrows. Neon lights, the works. This is just the basic data from Baseball-Reference, from 2016 to present. I left out the uncommon fielders of bunts, like second basemen.

I immediately knew these numbers lacked insight into the case of the known bunter, the case of Billy Hamilton. Perhaps influencing my preconceived notion was this: Hamilton does not tend to go to the third-base side.

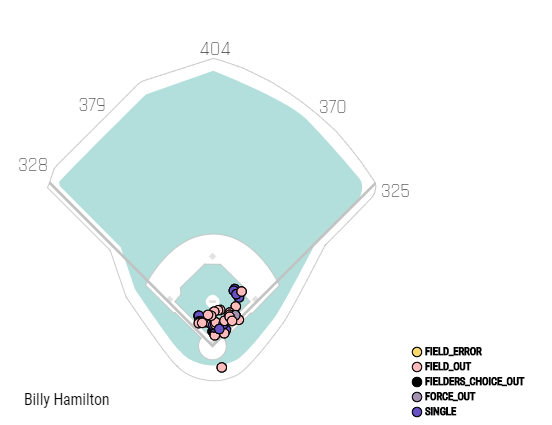

His bunt spray chart (there’s a phrase) is heavy on “right in front of the plate” and “toward first base.” Defenders, of course, are changing his calculus. Third basemen routinely stroll forward into the grass.

Statcast, via Baseball Savant, can tell us that on Hamilton’s non-sacrifice bunts dating back to 2016, third basemen have been, on average, 82 feet from home plate–a crowding only a few others, such as Mallex Smith, experience. Ender Inciarte, for example, instills enough doubt that third basemen line up 90 feet away on bunts he actually attempts.

A strong-armed defender, the strong-armed defender, is invading Hamilton’s space. He’s several steps closer to a potential rendezvous with the ball. He’s basically holding up a handwritten sign saying, “PLEASE BUNT. I AM READY NOW.” It would have to be difficult to look at a big-league third baseman in that state, bunt toward him, and plan to beat it out.

Seems reasonable enough. But then the question remains: Why is Hamilton so much worse at bunting than we’d expect?

***

Time to get this out of the way: All data and tables in the following descent into bunt madness are derived from Statcast data at Baseball Savant, dating from 2016 to the present to capture bunts with defensive alignment information. The data is also specific to left-handed bunts, so as to ensure everyone is running the same distance and performing the same action to land each bunt.

Statcast uses three infield alignment classifications: Standard, strategic, and shifted. Strategic alignments stop short of moving someone to the opposite side of second base, but can and do include looks where the third baseman plays in against a bunt attempt.

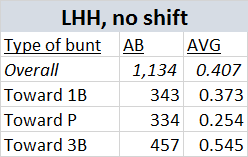

To move past the generalities of our overall numbers, the first thing I did was remove actual shifts from the equation–the type Joey Gallo can claim a hit against any time he wants.

OK, bunts toward third base are still coming out way ahead. The data does, however, give shape to the dilemma of defense. Third basemen, on average, start out 88 feet from the plate on bunts toward their side, but just 82 feet from the plate on bunts toward first base. It’s a sort of reverse measurement that shows they are influencing the hitters’ decisions. That made sense.

Then I ran a whole bunch of queries expecting to find that this influence came with good reason, that it made sense for Hamilton and other speed-first types to take bunts with them toward first base. Or maybe even try to engage the pitcher. That evidence … didn’t totally materialize.

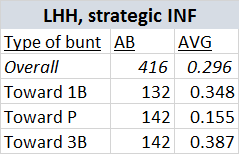

First, I isolated left-handed bunts against those “strategic alignments,” which Hamilton bunts against about half the time. In this league-wide sample–again, excluding sacrifices–third basemen lined up an average of 78 feet from the plate–closer than the average starting spot vs. Hamilton.

The difference is much smaller here, but third-base-side bunts remaining ahead at all would seemingly qualify as a massive shock, yes? It suggests that Hamilton should be directing at least the majority of his attempts toward the hot corner. All while he’s doing nothing of the sort!

Here’s a rare try of his that was directed at Nolan Arenado of the Rockies.

It’s not easy! Place another, lesser defender in the picture and it might be impossible. Dee Gordon singled twice on bunts to third base against the Red Sox and young Rafael Devers this past weekend, for instance.

You could see this point getting lost sometimes: The defense may be aware a bunt is coming, but the third baseman’s identity is also a card on the table. Phillies second baseman Cesar Hernandez has 13 bunt hits toward third base in 17 tries since the start of 2016, including four into “strategic” alignments. He has taken advantage of noted hot corner defenders Jose Reyes, Freddie Freeman, Adonis Garcia, and Ryan Flaherty in that span, among others. Hamilton (as a lefty) only has seven total at-bats that have ended in bunts toward third base in our time frame. Four have resulted in hits!

I’m officially starting to be swayed: Hamilton might be missing opportunities.

Disregarding the specific fielders, the numbers insist that there is more room for error, confusion, or general fielding difficulty on the third-base line–even with the scales tilted by sheer awareness that something is up. I wanted to be totally sure, though. Having noticed that some bunts that ended up as hits came in potential sacrifice or squeeze situations, I sought to isolate the most Hamilton-esque bunts–where a defense is challenged only by the hitter’s speed. I whittled the sample down to left-handed bunts that occurred with the bases empty (still keeping shifts out of the equation).

I think I give up? Send your bunts toward third base. I mean, why aren’t more bunts going toward third base? Why don’t all of Hamilton’s bunts go toward third base? Hamilton has only attempted five bases-empty bunts toward third base in the past three seasons (going 2-for-5), while Hernandez has run up a tally (10-for-12) and others like Gordon (11-for-22) and Gerardo Parra (7-for-10) clearly have it in the toolbox.

Hamilton is dealing with more encroaching defenders, absolutely. Still, he has attempted 23 bases-empty bunts toward the mound or first base and gone 6-for-23. Is this really just a long-running misjudgment? A case of the defense being more effective as a deterrent than anything else?

I’m still sure there is some aspect of this whole thing I’m missing. I’m not ready to provide a prescription or a lifehack for the fleet-footed baseball players who lack pop. I just have different questions now than when I started.

We seem very certain that a third baseman is a better fielder than the other infielders who might encounter a bunt. But are we sure his surplus competence isn’t overwhelmed by the difficulties of his assignment? Throwing across the diamond at an odd angle, often in the process of contorting his body, and sometimes while attempting to grasp the ball for the first time, is an unthinkable challenge.

Compare it to a pitcher underhand flipping a ball fielded on the first-base side. You don’t have to exchange many of the latter play for the former before you start hitting pay dirt.

Are hitters deciding where to place their bunt based on the defense? The situation? Are their snap judgments informed by anything other than the view from the batter’s box? We encounter these all the time, aspects of baseball that look simple right up until they aren’t. Though I underestimated it, I now believe that even the humble bunt might be among those things, influenced by a crossfire of mechanisms that require far more than the naked eye to truly understand, far more than common sense to fully capitalize upon.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now