He had never really been able to discern whether his love of Fight Club informed his foray into cloning or if his interest in the highly controversial process predated his affinity for the novel. In any case, he found comfort in the likeness of the two, although cloning required a mere three rules: under no circumstances do you talk about cloning, never involve more than two guys in the process, and always choose white dudes capable of growing beards.

Constrained by the societal norms that had infiltrated the world of professional baseball, it took him two years to pluck up the courage to release his project into the world, despite having had the clonee within his grasp since the two first arrived in Atlanta in 2006. In the ensuing four years, Matt Diaz blossomed into the perfect specimen: capable of playing baseball at an elite level and yet completely forgettable. The second piece arrived in the 2009 offseason in the form of a light-hitting outfielder who was completely unknown to the National League and also contemplating retirement.

The cloning went off without a hitch. The real Eric Hinske quietly retired to spend more time with his family, the real Matt Diaz and the cloned Matt Diaz looked different enough to pass as separate players, and both were off the team after 2012. His work was good enough to earn a promotion to Assistant General Manager.

After he was sure there remained no memory of the existence of Matt Diaz, a memory scrub that took approximately three seasons, he again began the cloning process. This time, though, he used a pitcher who was a little more memorable, perhaps, than Matt Diaz, but had the integral quality of being a redhead and therefore identical to every other redhead in existence. Months after trading for Shelby Miller, he lured the pitcher into the laboratory on the pretense of a meeting concerning his contract status. Three days later emerged Shae Simmons, a right handed pitcher with as much promise as Miller. The latter had an All-Star season before being traded while the former toiled away in the minors. Nobody suspected a thing. He was promoted to General Manager at the end of the season.

Encouraged by the success of his first two experiments, he drew far more ambitious, wanting two major-league calibre players on the same roster. But his plans were interrupted as whispers of misconduct made their way throughout the league. Determined to hide his work from the prying eyes of his competitors, he did all he could to throw officials off the scent. It worked, and he was banned for life in November of 2017 for violating international signing rules. His work, however, lives on in the organization.

You will never be exactly what you wish you could be.

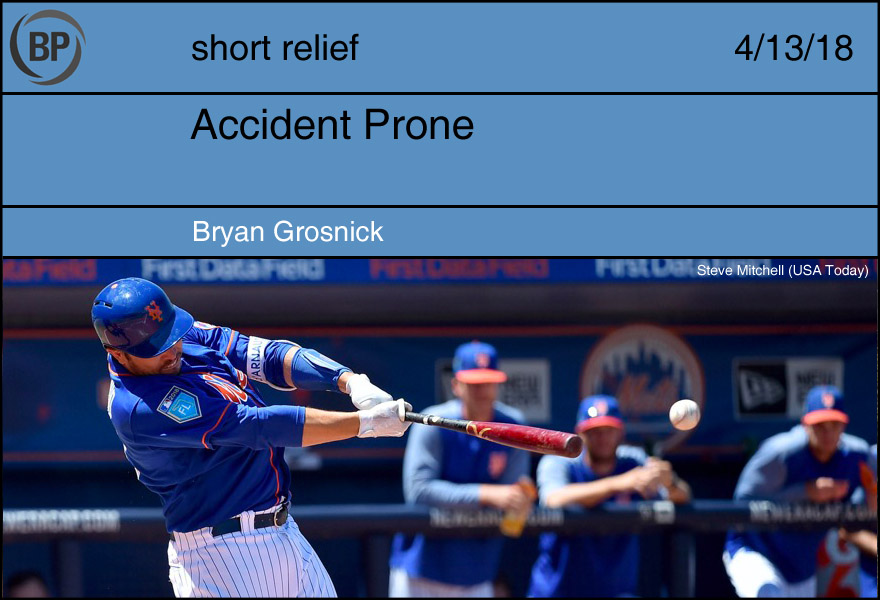

Travis d’Arnaud’s professional baseball career has been a series of injuries, occasionally punctuated by a baseball game. If you told me that he pays rent on his own private suite at the Hospital for Special Surgery, I’d believe you. Even before we found out last week that he’s got a tear in his UCL–one that might eventually require Tommy John surgery–he had an impressive laundry list of terrible injuries.

Here is said (incomplete) list:

- Three concussions (or more)

- Broken foot

- Broken hand

- PCL tear (knee)

- Rotator cuff tear

- Herniated disc

- UCL tear (elbow)

The injuries robbed him of time: playing time and development time. He’s now 29 and has less than 400 major-league games to his name, despite being a top prospect or major-leaguer for over a decade. Never mind that he was highly-touted enough to be traded for a recent Cy Young winner … twice! … TdA will likely be considered something of a “bust” in prospect circles and you could put fair odds that he’ll be out of baseball within five years.

This is not an uncommon story. No matter how much we achieve, or how well we write our own life stories, time comes for all of us. Whether we don’t get the opportunities or time runs out, or we just give up because it is too hard, we never get the lives we imagined for ourselves. At some point, Travis d’Arnaud must’ve thought he’d be an All-Star, if not a Hall of Famer. Heck, I did, and I stopped playing organized baseball at 13. Even if he only ever dreamed of spending 15 years with a team, it might be time for that dream to disappear.

If those are the dreams that he once set out for himself, he’s going to have to let them go, and find new ones. And yet:

You are not just your catastrophes.

Travis d’Arnaud’s professional baseball career has been a series of outstanding successes, occasionally punctuated by disappointments. If you told me that I could regularly be considered one of the top twenty or thirty people in the world at my job, have my work valued at millions of dollars, and regularly get cheered by 20,000 strangers, I’d probably start crying tears of joy on the spot.

Every once in a while, someone inside baseball puts a tremendous amount of value on this man. Twice, teams have traded the world’s greatest pitchers for him because they see his own greatness. Front offices have given him starting jobs and massive contracts. Baseball media members write glowing reviews of his skills and rate him as one of the 20 or 30 best prospects in the world. Best of all, several times a year he performs incredible physical feats that almost defy description. He lofts blazing fastballs hundreds of feat, into the fists of adoring fans. He performs David Blaine-esque slight-of-hand tricks to fool umpires by slightly changing the appearance of a pitch.

Best of all, this guy has been knocked down (literally and figuratively) more times than I can count and he keeps getting back up and fighting for his spot and for what he wants to do.

We could look at our lives through the lenses of the little mistakes at work, the missed opportunities, the heartbreaks. Or we could try to look at our lives as something greater than our failures. We get to choose which Travis d’Arnaud we want to be.

Wade Boggs would eat chicken and dumplings pregame. Jose Valverde would never step on the foul line. Adam Dunn would strike out at least once a game. Superstition comes in many forms, and we all have opinions on them. They’re neat! They’re useless! They’re not even worth getting mad about, just let the athletes have their fun. There might be, at some base level, a science to it. And I’m here to tell you that, from personal experience, they work.

This post was of course a vainglorious excuse to mention that I won my curling club’s men’s league championship this week. Our team wasn’t the best all year — specifically third-best out of the 10 teams. Good enough for a first-round bye. And I had my own routine: leave work, pick up the kid from preschool, go home and eat a quick dinner, drive to the club, and curl.

On the first week of playdowns my hair was a bit ragged and greasy; I forgot to wash it that morning. So I reached in the back for whatever hat I could reach. It was an Astros hat. Hey, they did good in the playoffs. And I remember thinking to myself, hey, maybe I should make this a lucky hat.

So that’s what I wore during each of the three playdown games. I was also sure to wear gray track pants because that’s what the USA men’s curling team also wore on their winning streak en route to a gold medal. It was my first ever league title. This obviously had to make a difference. I never did these things before in all the times I didn’t win my league.

Of course I can’t wear the pants and hat every time because I simply can’t win every game. Losing happens to everyone, even the Astros. So I’ll break them out only when I absolutely need a W, and only until it stops working.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now