Major League Baseball Idealized in Cake

By: Mary Craig

Baseball is great, but baseball is also very bad. And it’s this contradiction that draws us to the sport and drives us to madness with its presence in the summer and absence in the winter. Sometimes it’s so bad in the summer that we consider finally walking away from it because we deserve so much better than what it offers. And then winter hits and baseball has walked away from us and we find ourselves listing off all we would do to bring it back even for just the day.

But here’s the thing. Thanks to the existence of technology, we don’t have to spend our winters baseball-less. In fact, we can enjoy the good of baseball without any of the bad. No, I’m not talking about the winter baseball leagues, though those are also a fine substitution. I’m talking about the Great British Bake Off.

For those unaware of the program, it’s a delightful, anti-American show (There’s no prize money! There are no sob stories! The contestants are nice to one another!) formerly produced by the BBC in which 12 amateur British bakers compete against one another each week in a series of three baking challenges. The bakes are judged by Paul Hollywood (a man easy to dislike) and Mary Berry (everybody’s cheeky grandmother), and the show is hosted by comedy duo Mel and Sue, who infuse the show with a fantastical number of innuendos and puns when they’re not busy eating everything in sight.

You may have noticed that description does not contain any semblance of baseball, and you would be correct in the literal sense, but since baseball parades itself as one giant metaphor for America, a baking show can do the same thing for it. In fact, there are four key elements of the Bake Off that embody the same sentiments as baseball at its apex.

1. It effortly blends the traditional with the novel, showcasing classic desserts of the British past with new techniques and flavors. As a bonus, the elderly judges are eager to try the bakers’ innovations, including bread made with hemp flour (or, “the legal side of an illegal product,” as the hosts described it to the eight-year-old Berry).

2. Like the romanticized version of baseball, the Bake Off celebrates diversity and inclusivity; if anyone has a modicum of talent, they have a chance of doing well on the show. Over the seven seasons, the contestants have ranged from 66-year-old retired naval officer Norman (who considers pesto exotic!) to 30-year-old stay-at-home mom Nadiya (who is from Bangladesh and makes bubblegum-flavored cheesecakes!).

3. It makes for great background noise until there’s five minutes left in the challenge and it’s time to de-mold a mousse cake that may not have had time to properly set and suddenly you’re holding your breath and peering through your hands and it’s…holDINGTOGETHERICANTBELIEVEWHATIJUSTSAW!!!

4. The show thrives when it showcases its contestants’ personalities. We care as much or more about their friendships–the way they go on motorcycle trips together and poke fun at each other for putting royal icing in the oven–than what they produce.

The Bake Off might not be able to satiate your desire to hear the crack of the bat or the snap of the ball hitting the glove, but if you’re tired of a baseball world taken over by inane Hall of Fame debates, the show might be able to offer you something more.

The Newspaper

By: Matt Ellis

It feel somewhat a banality to declare that today we can stream games on our phones, watch them in bars, or cable packages. It’s undeniable that the migration of digital media has made following the game that much easier with the shrinkage of hardware and the mass expansion of software. And yet, like we covered last week–it’s important to realize that the proliferation of new technologies don’t inherently invent something new: rather, they exacerbate existing structures and technologies for making sense of the world.

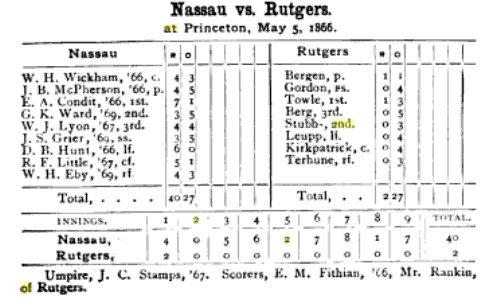

We already briefly covered the emergence of the scorecard in baseball history for this series, but I wonder what we might do in thinking about the emergence of the newspaper box score as a constitutive element of late 19th century capitalist modernity–a representation of a thing inherently representable (and, of course, profitable). Take a classic case as example:

Here, for instance, we have a box score published in a newspaper on May 5th, 1866. The first anniversary of the end of the American Civil War had yet to arrive, and the emergence of a new series of states in the late 19th century meant that newspapers, newspapers, were a constitutive technology of what was to follow. Just imagine for a moment: you’re a part of a world historical religious community: the power of the catholic church around the enlightenment, or Jewish eschatology. The language you speak is the same sacred language the priestly class speaks, sacred, of God, and then, suddenly: an account of a ball game represented by numbers in the newspaper which tells everyone who reads it that they are a Part of an Imagined Community. Baseball fans, Americans, Rutgers, Nassau citizens. Why else would this mean something to you? I quote Benedict Anderson on this:

“Before proceeding to a discussion of the specific origins of nationalism, it may be useful to recapitulate the main propositions put forward tus far. Essentially, I have been arguing that the very possibility of imagining the nation only arose historically when, and where, (fundamental) cultural conceptions, all of great antiquity, lost their axiomatic grip on men’s minds…No surprise, then, that the search was on, so to speak, for a new way of linking fraternity, power and time meaningfully together. Nothing perhaps more precipitated this search, nor made it more fruitful, than print-capitalism, which made it possible for rapidly growing numbers of people to think about themselves, and to relate themselves to others, in profoundly new ways.”

So just think for a moment: a new mode of relation between the literate, or the semi-literate. The 19th century is far from the 12th, but what does it mean that the grounds of this game were set out in a century before mediation became a televisual or technologically constitutive practice?

In short: we still score games using the same scorecard–and yet film and digital recording technology wants to argue a fundamentally new relationship between the kinds of images recorded: celluloid, which requires light bouncing off the filmed object onto the photochemical sensor, and digital technology, which converts said information into 1’s and 0’s. What do we make of the fact that the informational, essentially cybernetic ground for producing knowledge about our game emerges in this particular form, this 19th century artifact, which still to this day determines what kind of knowledge is privileged, deemed useful?

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now