(English translation: No Exit from Arbitration)

SCENE

A conference room in Deadball Era style. A massive bronze pitch clock stands on the mantelpiece.

ARENADO [Enters, accompanied by Tony Clark]: Hm! So here we are?

CLARK: Yes, Mr. Arenado.

ARENADO: [Taking in the surroundings] And some get used to this? Even after the tweets?

CLARK: Tweets? There are no tweets here.

ARENADO: I assumed there would be tweets. Given that this is the kind of place this is.

CLARK: [Laughing nervously] Ho ho, no sir! Stories told by those who have never set foot here, I assure you.

ARENADO: But there will be more soon?

CLARK: We are told there will be, the way things appear to be going.

ARENADO: Appear to be! Well that’s–[He turns around to discover he is alone, the door tightly closed. ARENADO pulls on the door, but to no avail. He begins to pound upon it.] Hello! Hello, where did you go? I was talking to you. [He crosses to the intercom across the room and presses the button, once, then twice, then leans his whole weight upon it. Meanwhile, the door opens, and GERRIT COLE enters.]

COLE: No one is coming, so you might as well stop that infernal buzzing. I’ve been here for hours. I promise you, no one is coming.

ARENADO: What do you mean, you’ve been here for hours? I’ve been here the whole time, I didn’t see you! I must have just missed you.

COLE: I stand six feet four inches tall. You did not miss me. I’ve been here all along. You’re the one who just got here. I’ve never seen you before.

ARENADO: No, that can’t possibly be it. I’m sure you’ve seen me. Lots of people have seen me. Do you see this mustache? It’s a wonderful mustache. All my facial hair is wonderful, and placed on my face with the careful precision of ships on a Battleship board.

COLE: I haven’t seen you, I’m sorry to say. Who are you?

ARENADO: I’m a New York Yankee.

COLE: I don’t think that’s true.

ARENADO: And who are you, to tell me who I am? Who are you, anyway?

COLE: I’m… not sure. [Holds up hand] I have 13.5 written on the back of my hand, but the people who put me here told me I’m 11. So maybe call me 12?

ARENADO: I don’t trust them. You can be 13 if you want to be. Call me…18.

COLE: It doesn’t seem to make much difference, anyway. [The clock on the mantelpiece strikes loudly, startling them both.] They told me that was purely decorative!

ARENADO: I thought I understood what kind of place this was, but now I’m not so sure.

COLE: Same–

[The door opens, and TREVOR BAUER enters.]

ARENADO and COLE, in unison: Oh.

Terror. That’s what defined my childhood, and for no real reason. My parents? Firm, but loving. Our home? Small, but comfortable. Our yard? A hub of imagination and wiffle ball, bordered by a corn field that, I assumed, went on forever.

The first thing that terrified me were thunderstorms. The explosions of noise and the threat of being sucked into the sky was enough to send me, at seven, scrambling into the basement, where I believed I was safe from nature (but not, as my sister gleefully told me, from radon poisoning).

But the terror was everywhere. It was on the pages of my dinosaur books, where an ornate illustration of their extinction–a meteor strike as they stampeded and panicked–was captioned by the hint that “it could happen again” was enough to put me in a numb, fearful haze for a week. Y2K, nuclear annihilation, worldwide pandemic; they all took turns being the source of my anxiety, often moments after I had learned what they were.

Already convinced plane crashes were a regular occurrence–that they were just dropping out of the sky like dead birds during a worldwide pandemic–my budding baseball fandom eventually met my unending worry once I realized the teams I loved had been traveling via plane for decades. What I didn’t know was that the American League had considered this a real enough prospect to plan for it, this week in 1957.

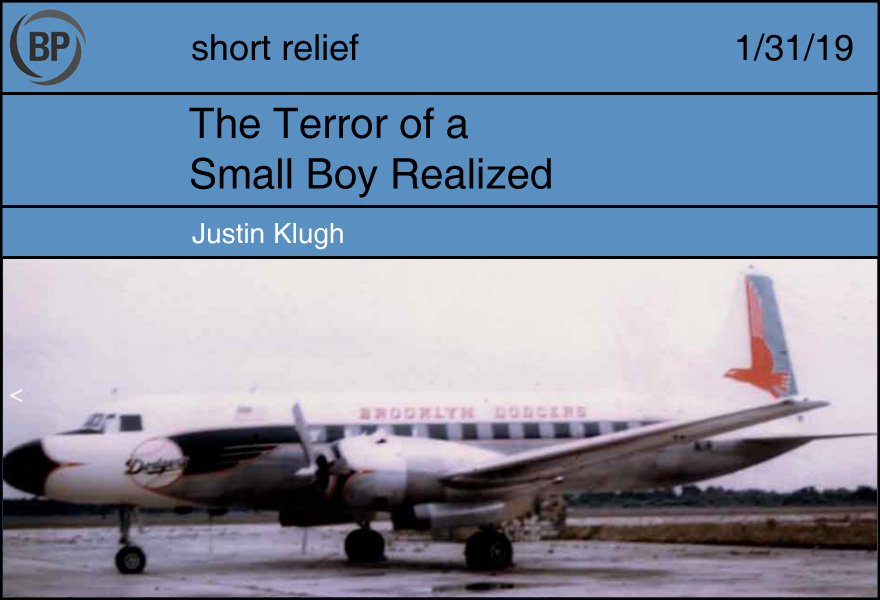

The Brooklyn Dodgers were the first team to acquire their own airplane that year, a Convair CV-440 Metropolitan with “Brooklyn Dodgers” written in red on the side, for $775,000. The surge of air travel among teams led to the decision to develop a league wide “catastrophe plan,” and it was submitted by a three-man council led by Red Sox GM Joe Cronin at a meeting between the Junior and Senior Circuits during the offseason. Each team was to give the league a list of ten names from their roster who would become available for an emergency draft should a team suffer a plane or train disaster.

But what if, someone actually wondered, the affected team tried to use the saddest, darkest of circumstances to their advantage?

“In order to keep the club that is affected from buying all the good players, a price of $50,000 for the first player, $75,000 for the second, and $100,000 for the third has been proposed,” came the grim response from the International News Service wire.

Like me as a child, someone had thought ahead to the worst case scenario, and you best believe that if I had heard of such a plan existing, I would have reviewed the schedule, a twinge of panic bursting through me each time I discovered a road trip. Unlike me as a child, however, baseball refused to dwell on its fears until bedtime, ruining things they otherwise looked forward to, like dinner and Nintendo. To close out the story on its “catastrophe plan,” the INS conveyed that this was simply one administrative matter on a crowded docket.

“Also,” it read, “on the agenda is a proposal by the American League to adopt a three-game playoff in case of a possible pennant tie.”

I received an anonymous gift in the mail last November, a 2016 Topps Ian Kennedy card. Why would anyone send this to me, and anonymously to boot? I don’t collect baseball cards. I don’t think I’ve even held one since I was a little girl. I’m not known as a Royals fan, so this was a head-scratcher. I have spent a lot of time since November thinking about Ian Kennedy. What does he have to do with me? Maybe everything? He’s had his ups and downs. He’s experienced injury and success. Through it all, he’s had his hopes and dreams, and now, as he prepares to report, he’s been working hard for an unpredictable future. Yes, I think that’s it. That’s me.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now