On Monday morning, I’ll be at my annual optometrist appointment, trying not to blink at the little puff of air during the first stage of the glaucoma test, trying not to squint against the lights bright and brighter, trying to decide which of the two lens options really is better in the series of minute adjustments that will determine my new prescription. Though I’m a pretty lucky glasses-wearer, one who can read a book in my hands and also drive without the corrective lenses (at least thus far), going without them for more than a few minutes leaves me with a terrible headache. This is due to my eyes’ inability to switch focus effectively; they want to remain fixed on one thing, near or far.

***

On Friday night, I watched my first full baseball game in a month, and coming back to baseball with this particular weekend in Philadelphia has been stepping from a cave into floodlights. Maybe that’s just right, honestly, for this particular weekend and its four-game sweep and a celebration for the 2008 World Series team: an exercise in so many different kinds of too much, an exercise in shifting focus fast and faster and more than simply past to present.

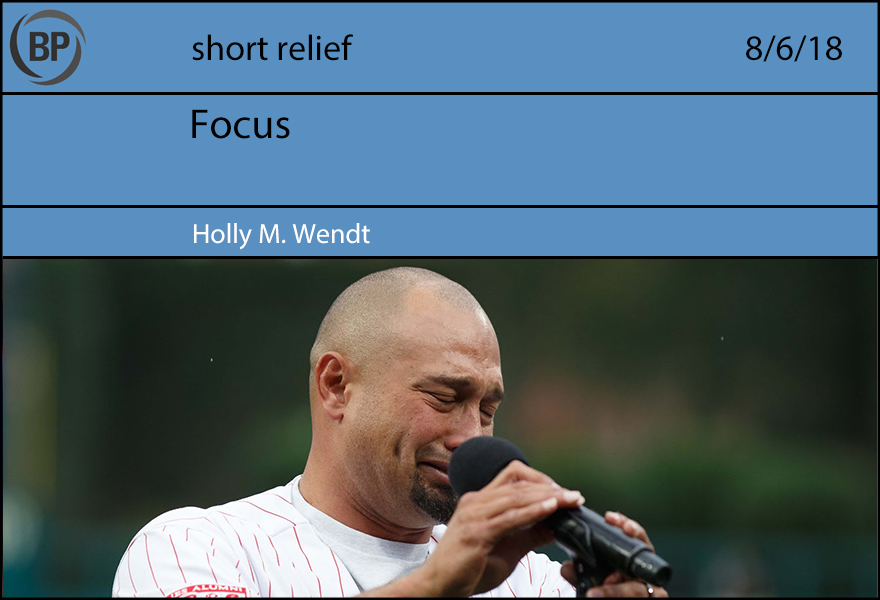

After walking things off with a three-run homer on Thursday, Maikel Franco treated fans to a defensive show on Friday—Friday, the same day that Shane Victorino made official his retirement from baseball. Watching Shane Victorino wipe away tears was, I thought, the ultimate emotional kryptonite. I was glad for Vince Velasquez throwing a gem of a game—one that included Velasquez hitting a double of his own—to temper the clear and present marker of one age passing.

Then came Saturday: Pat Gillick and Roy Halladay’s enshrinement in the Phillies’ Wall of Fame. Carlos Ruiz was the one to tug the cover from Halladay’s plaque. It was fitting in the most heartbreaking way, a tender and keen reminder of all that Halladay’s family and friends and fans had lost and all that we’d been gifted all the same.

And then there was Brett Myers, featured in the television broadcast with all the rest of the 2008 squad that was able to attend—Brett Myers, whom witnesses saw punch his wife in Boston in 2006 and was subsequently charged with assault, who berated a reporter with abusive and derogatory language in Philadelphia in 2007, and who did not receive a formal suspension from the team for either incident.

On Sunday afternoon, the Houston Astros released a farcical statement regarding their acquisition of Roberto Osuna, one that really seems to frame the Astros as doing some kind of public service, some kind of boon for victims of domestic violence by signing Osuna because of “awareness,” and not because the Astros have decided that attempting to win baseball games is worth any cost.

My favorite team has already been culpable of the same kind of behavior. I’m not searching for high ground here. But I’m reminded, again and again, how quickly my acts of fandom ask me to change focus, to direct and redirect my attention. I’m reminded, again and again, how important it is to really see what’s here, all of it, and name it, even when—especially when—it’s what I least want to see.

Mickey Callaway, the manager of the Mets, is going to speak to the press at 4 PM EST today. Matt Harvey, rather than accommodating that schedule and speaking to the press at 3:45 or 4:15, as the Mets requested, is going to speak to the press at 4 PM EST today. This is glorious and wonderful and exactly the type of pettiness and vengeance we need more of in baseball, rather than perpetual beanballs, fisticuffs, brouhahas, and other violence-related activities.

The key here is that the retaliation should be aimed not at his former teammates, who should be viewed as his brothers in war against the Wilpons, but at those who align themselves, eagerly or passively, with those malfeasors. Thus, for example, perhaps Harvey should rent the house next door to wherever the Wilpons have their summer place in the Hamptons and, rather than engage in the late-night activities on the town that he is famous for, have some raucous in-home and on-beach entertainment. Fireworks and a live band, say. Or, a twist on a theme: a lovely, sedate party, the occasion of the summer, the place where one simply must be seen … with no invitation to the neighboring ballclub owners. The scandal!

Harvey could also be less showy, less obviously out for vengeance, and instead keep his activities quieter, which might needle management all the more. Say, by ordering copies of The Art of Connection: 7 Relationship-Building Skills Every Leader Needs Now, Understanding Workers’ Compensation: Managing Workplace Injuries and Lowering Costs, and The Total Money Makeover: Classic Edition: A Proven Plan for Financial Fitness to be delivered to the Mets front office. Gift-wrapped, of course, with a card signed, “Love, Matt.” Love, as they say, trumps hate.

Harvey has a variety of options, including others following the press-conference theme (taking the 3:45 slot, for example, then filibustering essentially until game time), which may grant him varying degrees of satisfaction. I encourage his selection of some or all of these methods, setting an example for all to follow in the future.

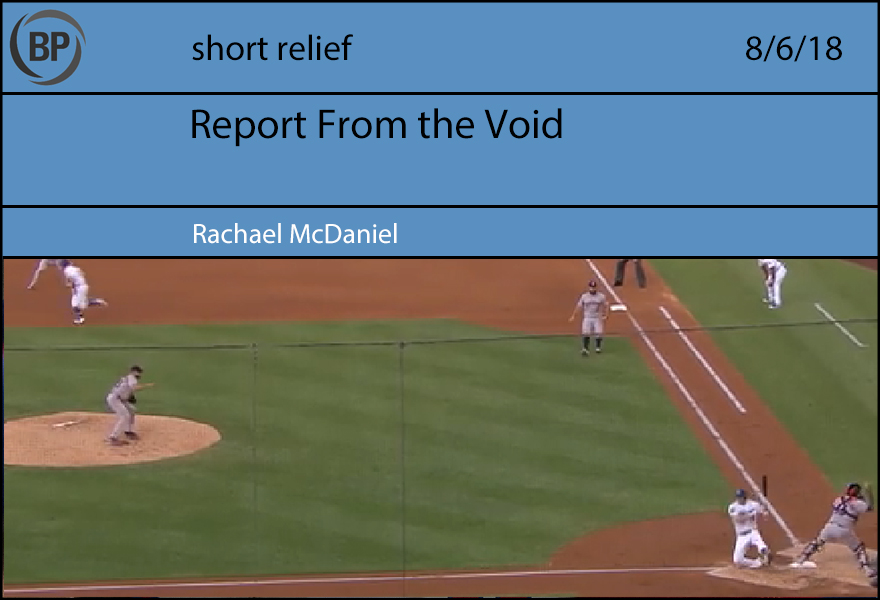

The Dodgers lost 14-0 to the Astros on Saturday, their worst loss in Dodger Stadium history. It wasn’t an outcome that you really expected, even after the Astros took the lead. Lance McCullers, Jr., who started the game for the Astros, left with an injury in the fifth; the Astros’ lead remained at a noncommittal 1-0 until the top of the sixth. There was an illusion of closeness maintained, keeping you checked in long enough to feel that you had wasted some time on the losing effort—long enough to feel insulted at having been strung along for this long.

In the bottom of the third inning, well before things got out of hand, Austin Barnes hit a leadoff single. This was encouraging; this was a run-scoring opportunity. Kenta Maeda was up to bat next. McCullers’ first pitch was a ball; his second was, predictably, a bunt attempt, though one gone foul. On the next pitch, for whatever reason, Barnes took off, while Maeda took a massive, uncomfortable swing at a middle-middle fastball. Martin Maldonado popped up, firing to second; Maeda, perhaps in reaction to that, and perhaps in reaction to his egregious own swing and miss, crumpled like a plastic cup in a fire. Barnes was out at second. It was all for nothing, in the end, all that chaos and expectation. Maeda had to pick himself up out of the dirt in the box, having looked rather foolish, now with no one on base. The purpose of his plate appearance had essentially been negated. What was he still doing up there? What was the point of all this?

McCullers’ next pitch missed its spot badly and got away from Maldonado, trickling almost to the backstop. But it caught the bottom of the strike zone for the inevitable strikeout. Maeda stood there for a while after he’d been called out; he watched Maldonado chase after the ball, watched him run back to the plate. Only then did he wander away, back to the dugout. Maldonado applied a tag to his arm almost as a courtesy.

There were only two out, and it was still only the third. There was lots of time for the Dodgers to score a run and tie it up. But there was something distinctly sad about this plate appearance to me. Maeda had put all that effort in for nothing. I probably should have turned the game off then.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now