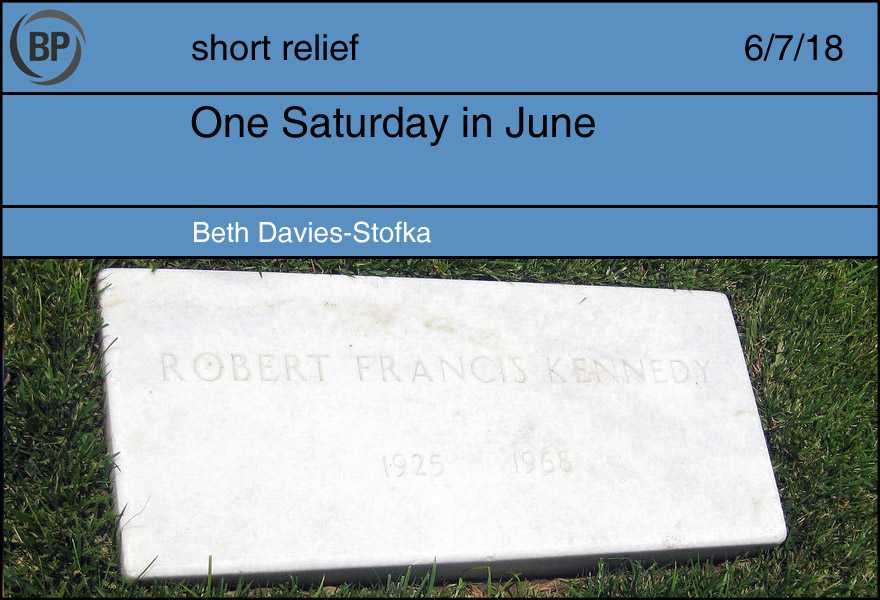

One Saturday in June, a little girl opened the door to the hall closet and a stack of newspapers slid out. She squatted on the floor to look at them. The paper on the top had a photo of a man lying on the floor in a halo of light, surrounded by worried people. The man didn’t seem to see the chaos around him. He stared into the distance, seeing nothing.

The girl had been conscious lately of the gravity in the house. She didn’t know grief, but it felt important, and it hushed her as she made the familiar circuit with her mother – the grocery, the bank, the dry cleaners. Something very sad had happened to someone very special. The grownups were heavy with it. Now, she was sure, she was looking at a picture of it. They were sad about that man.

Her mother called from the kitchen where she had been talking on the phone. “Come with me right now. Wear your hat.” There was something so urgent in her mother’s voice that she didn’t dare drag her feet. She ran to her room to put on her sandals and get her sun hat. It was a hot day. It was almost unbearable. But her mother insisted on walking down to the tracks in a hurry.

Dozens of people were already there, watching a train approaching. She heard someone say it was twenty-one cars long. Was that a lot? She wasn’t sure. The train was so long that she couldn’t quite take it in. It was taking forever to pass. People all around her were crying and sobbing; some were kneeling in the dirt and praying.

Born into turbulent times, she was used to seeing grownups cry. This was the second time in two months that she had seen men and women on their knees, sobbing and talking to God, asking for comfort and blessing. At four years old, she didn’t know that this was strange. As far as she knew, this was life – and life hurt.

She looked up at the two boys standing on the junction box nearby. Their shirts untucked, the green and white stripes of their stirrups disappeared into their sturdy shoes. Boys were usually pushing each other around and making a lot of noise, but these boys were motionless, their caps over their hearts as they watched the train slide by. She wanted to climb up there and be with them, solemn, honest, strong.

If only I were a boy, she thought, then I could play baseball. I’d be free.

Shohei Ohtani, the Angels’ multi-talented phenom, has already performed feats with his bat and his arm that no baseball player has done since the early years of Babe Ruth. Not content with the divides he has already spanned, physically and metaphorically, Ohtani announced in a press conference yesterday that he would also take over color commentary for the team’s Japanese television broadcast on days that he pitches.

While baseball players are no strangers to the broadcast booth after they retire, and occasionally, like Chris Archer, provide excellent commentary in postseason broadcasts, no player since the deadball era has attempted to call his own game on the field. The only recorded example of a pitcher/broadcaster was Ed “Mouth’ Donnelly, of the 1912 Boston Braves, who in an era predating radio and public address systems, simply yelled out his own running commentary about the game as it proceeded. Fans and teammates alike were initially amused by this novelty, particularly when Donnelly would criticize his own pitching in retrospect, but as the Braves’ season worsened, the swingman’s broadcast style devolved into conspiracy theories and dark, Lovecraftian horror vignettes, and the team was forced to move on without him in 1913.

Ohtani is confident that his attempt at two-way narration will go better. Through a translator, he offered: “This is something I’ve taken very seriously since first coming to the United States. In my spare time, when not practicing my hitting or my pitching, I’ve worked to improve my broadcasting skills. While waiting in the cages for my turn, I will challenge myself to think of as many different words to describe home runs, or the color green.” The young star has also practiced calling his own games of The Show, though he recognizes it is not the same thing. “I am always working hard to improve and to contribute to the Angels baseball team,” he concluded.

If all goes well, and he doesn’t encounter a sore throat or other setbacks, Ohtani says he believes he’ll broadcast his first performance soon after the All-Star break. After that? “I’ve always been interested in the early, oral traditions in both western and eastern literature,” he laughs. “Maybe I’ll compose an epic poem, like Beowulf. When we play the Astros.”

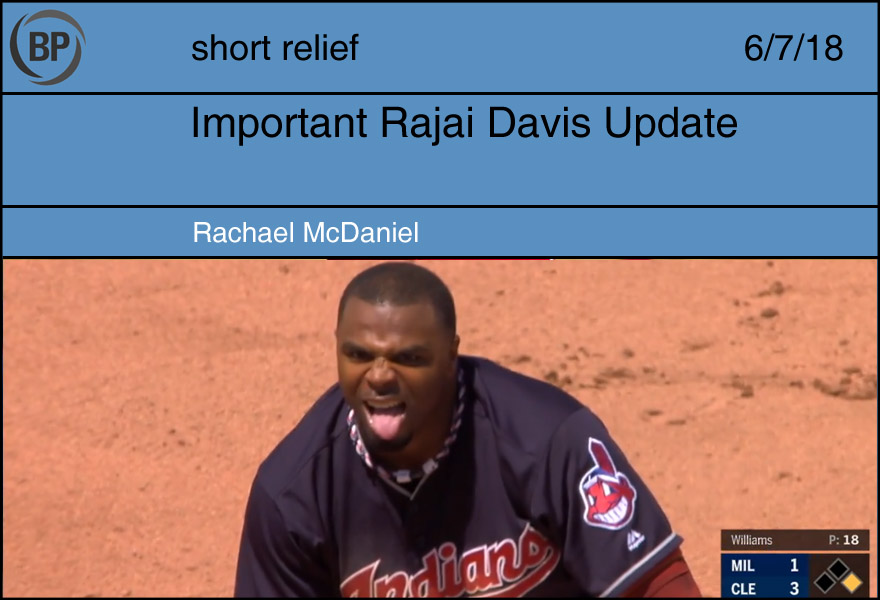

Rajai Davis almost got hit by a pitch on Wednesday afternoon. It was headed straight for his elbow, and it was baffling that he managed to get out of the way. It looked like it hit him. It sounded like it hit him. I certainly thought he’d been hit.

And yet, somehow, it didn’t. He spun around, unscathed, and tossed his bat aside in disbelief, his face a picture of cool and determined discontent. He looked like a protagonist in an action movie, immune to the laws of physics and possessed of superhuman skills, who’d just managed to evade a volley of bullets sent in his direction. Oh, now you’ve done it, his face says, but in a way that lets you know he was never in any real danger, and your pathetic attempt to rattle him would never have worked. The broadcasters speculated that the ball might have gone through him.

Davis took a walk. But that didn’t mark the end of his supernatural escapades. As Francisco Lindor swung and missed at a ball in the dirt, making the second out of the inning, Davis took off for second base. The throw from Eric Kratz was a good one; I thought they had Davis dead to rights.

But, once again, he emerged unscathed. He had stolen second, somehow. Reality had slowed around him, and he was safe, in defiance of the stars. It was his second stolen base of the day. He finished the game having reached base three times and stolen three bases. He was clearly enjoying himself, and it was incredibly fun to watch.

This was the first time I remembered watching Rajai Davis this season, and I was surprised. He had been an aging player, not as good at the plate or in the field as he once was, back when he hit that magical, reality-warping home run in Game 7 of the 2016 World Series. I was surprised not only that he was still playing on an almost certainly playoff-bound team in Cleveland, but that he seemed to be doing so well. I had assumed, after his poor season last year, that he had faded away, out of the world of baseball. Had Rajai Davis, at age 37, tapped into a fountain of youth without my knowledge? I found the idea encouraging for some reason. It was nice to see someone out there on the field having that good of a time, in such defiance of the way I thought things were.

I checked the stats. In reality, Rajai Davis is batting .223/.282/.255.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

huge JFK fans & naturally thought that Bobby could get us out of that damned war.

Catholic homes in a very Catholic city like Pittsburgh were in shock