Welcome to Ohtani Week: a celebration of, well, Shohei Ohtani. There’s been no player more fascinating or exhilarating since Ohtani graced our shores in 2018. Over time, the initial curiosity and excitement surrounding MLB’s first true two-way player in a century morphed into something more: Pure, uncut awe derived a superstar breaking barriers previously thought unreachable. All week, we’ll be talking about the most lovable—and possibly most talented—man in baseball. So throw on your Angels cap, grab your laptop charger, and dig in.

At this point in Ohtani week, we’re all well-aware of the historic, unprecedented deeds of our favorite Japanese superstar. As a two-way player in a modern game that basically never sees them, Ohtani’s mere presence on the mound is almost a miracle. But it turns out that the Angels standout is not only defying the current era’s de facto prohibition on playing both sides. He’s got a decent chance to end up with the most two-way playing time of any player in history, narrowly (and fittingly) outstripping Babe Ruth’s 1918 record.

Often lost in the glory of Ohtani’s towering homers, 100 mph heaters, and a vigorous yet vacuous debate about his status as the face of baseball is the mere fact that it is very, very taxing to play baseball. Many a budding superstar or Hall of Famer sees his season or career derailed from the relentless grind of the major league season, which demands a near-everyday commitment for about eight whole months. It’s a longer and more demanding ask than in nearly every other sport played at such a high level.

And yet, here we have Ohtani, who is not only playing nearly every day as a hitter, but also racking up about 20 starts’ worth of time as a pitcher. In effect, Ohtani is enduring the physical demands of 1.5 regular seasons, and doing so while throwing 100-plus mile per hour fastballs, a task that’s been known to eviscerate many an arm.

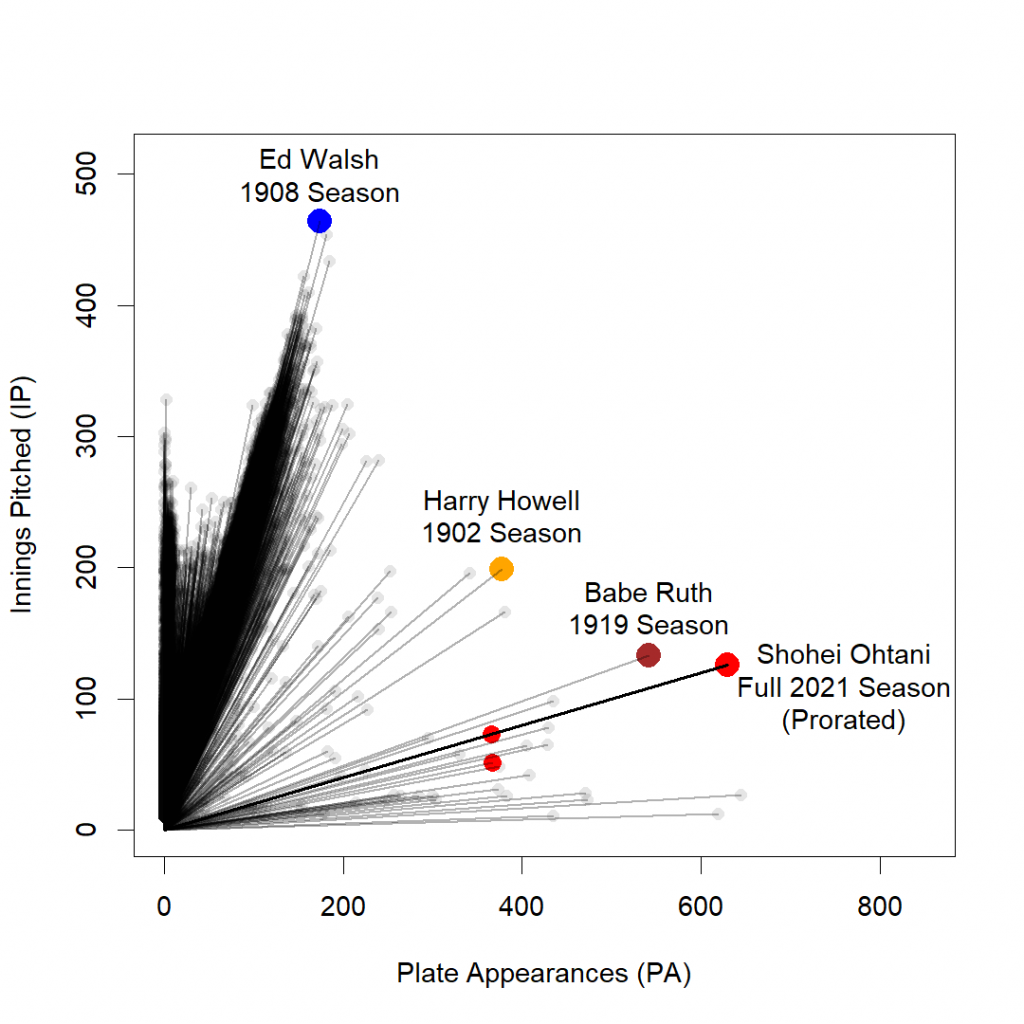

In examining the historical precedent for getting this much playing time, it turns out that the answer is quite simple: there really isn’t any. A simple way to view Ohtani’s exertion is to total up his plate appearances as a hitter and his innings pitched as a pitcher. The sum of these two numbers is a rough measure of his two-way labors, and can then be compared to almost the entire stretch of major league history. (For clarity, this chart and analysis omits non-two-way players.)

This chart shows the players with the most career PAs and IP in a season, with a line drawn back to the origin of zero PAs and zero IP, where all of us non-MLBers sit. For a lot of professional baseball’s history, managers expected pitchers to start and finish the game, leading to massive innings totals and a fair amount of at-bats because pitchers would still come to the plate in the seventh, eighth, and ninth. Then the reliever revolution came around, and for the most part, pitchers are now only called upon to deliver five to seven innings and rack up fewer at-bats. This led into the current era of relatively few two-way players in which we find ourselves.

Babe Ruth’s 1919 stands out because he has the most combined IP+PA of anyone so far: 542 PA and 133 innings. Ohtani is on track to match his innings total and exceed his time at bat by a cool 100 plate appearances.

Though Ruth is famous as a two-way star, for the most part he was either a pitcher or a hitter, and rarely both simultaneously. In the first half of his career, he was primarily a pitcher; in the second, mostly a hitter—he started only five games after 1919. That ‘19 season is one of the only times he tried to do what Ohtani is accomplishing now, and immediately afterward, Ruth abandoned his attempt, saying “It is too hard on the arm to play every day and then take your turn in the box. I found that I was never effective that way.”

But what killed Ruth’s two-way career is apparently no obstacle to Ohtani (so far). Of course, the fatigue requirements of 1918 baseball are likely significantly less than what modern MLB players deal with. Pitchers routinely ice their entire arms after starts, and though Ruth was quite a good pitcher, it’s safe to say he wasn’t tossing triple-digit bullets or knocking 120 mph exit velocities. From a sheer physical perspective, what Ohtani is accomplishing by achieving even similar playing time to Ruth is massively more impressive.

An important caveat here is that we’re lacking Negro League data, which holds the last true set of two-way heroes in any way comparable to Ruth or Ohtani. Negro League stars like Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe simultaneously hit and pitched, piling up absurd amounts of PAs and IP in the process–on a per-game basis. (For example, Minnie Miñoso went to the plate 742 times per 162 games, but never played more than 47 games in a year.) Negro League seasons were drastically shorter than the roughly 150-contest, six-month seasons MLB has had throughout its history. Because of that, it’s hard to draw any meaningful comparison between what Double Duty and other greats did versus Ohtani, Ruth, and others.

Ohtani still has about 60 games worth of playing time before he finishes the full season, and as he’s already discovered, any one pitch can end his hopes by snapping a ligament or tearing a muscle. It’s not a sure thing that he’ll be able to take this record, but even the attempt is astounding. The only historical comparisons that are even close were forged a century or more ago, when the game was an entirely different sport. Nowadays, with a pool of player talent encompassing not only much of the US but also a significant part of the world, and physical demands so extreme that they can easily break bodies down, simply making and staying in the majors is a rare accomplishment.

This is why playing time stats don’t get the glory they deserve. Racking up lots of PAs is treated as the equivalent of an attendance award: so you made it into a lot of games, who cares? But in Shohei’s case, he is accomplishing what used to be unimaginable. Not only is he playing nearly a full season as a hitter, he’s also going to end with nearly a half-season’s worth of pitching time. And that feat has never been equaled–not even by Babe Ruth.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now