In the final hours before his death, to the surprise and dismay of his closest friends, Socrates refused to flee into exile and instead imparted his beliefs concerning the importance of technology in baseball. His ideas on the subject were immortalized in one of Plato’s best-known dialogues, Phaedo (from which we get the dog’s name Fido). The philosopher’s thoughts influenced generations of baseball elites, and thus are worthy of revisiting here:

“The one aim of those who practice the game of baseball in the proper manner is victory. No one who eagerly pursues victory all their lives would feel resentment upon winning. But those who lose unfairly will feel resentment indeed, perhaps all their lives. All effort, therefore, should be made to reach a fair and impartial decision. The only good is knowledge and the only evil is ignorance. Decision-making must be perfected. Thus arises the subject of technology.

“Getting it right in baseball,” the great man said, “sometimes hangs on moments which last mere seconds. These seconds, on the bases or at home plate, are invisible to the naked eye. Therefore, the umpire, in his devotion to the perfection of victory, subjects the bang-bang play to lengthy scrutiny. After all, is it not true that the unexamined play is not worth playing? In such moments, the perfect victory is surely secured when confirmed by video recordings. These should be repeatedly replayed from every possible angle until such time as managers are out of challenges or everyone present is otherwise exhausted.

“In this same way, it would be ridiculous for the umpire, devoted to perfection, to oppose the introduction of an automated strike zone.

“You see, my friends, technology allows us to separate the body as far as possible from the game. By this means, the game of baseball is freed from the bonds of the body’s imperfections. The most perfect of umpires does not associate sight with his decision, nor does he drag in any sense perception. Rather, using algorithmic measure alone, each call is pure.

“The nature of technology is to free the umpire as far as possible from the use of eyes and ears, whether at the bases or at home plate. In a word, the game of baseball is freed from the whole body and its confusions.

“For this reason, baseball’s principal preoccupation must be the separation of the body from the game. Victory, the single desire of all those who practice the game of baseball, is assuredly perfected when the game is turned over to cameras, sensors, and computers.”

As he lifted the poison to his lips, Socrates’ last words were believed to be, “Jim, we owe Armando an out. Please, don’t forget to pay the debt.”

The Toronto Blue Jays, despite starting the season surprisingly well, have backslid somewhat of late. On Tuesday night they suffered a 12-2 loss at the hands of the Mets, made all the more unbearable because of how long the start of the game had been delayed. The culprit was, as it usually has been over the past few weeks, bad starting pitching. Jays starters currently hold a 5.69 ERA, second-worst in baseball.

Among these poor Jays starting performances, one man has been, up to this point, kind of okay. That man is J.A. Happ, who has been kind of okay for most of his career. Entering his start on Wednesday morning, it would have been reasonable to expect yet another kind of okay performance from Happ. Jays fans would certainly have been satisfied with anything less than terrible.

What the Jays ended up getting from Happ was not just a seven-inning, two-hit, 10-strikeout effort to back up their tit-for-tat 12-run shellacking of the Mets’ pitching staff. In his four plate appearances, Happ recorded two hits and a walk with two runs scored — not only a shocking and unexpected display of hitting prowess from an American League pitcher, but the possible emergence of a new two-way superstar the likes of whom the game hasn’t seen since Shohei Ohtani debuted so many months ago.

Baseball’s lack of truly marketable stars, especially stars that will appeal to young people, has been oft-lamented. There is no one better than J.A. Happ to fill that void. He has all the qualities to appeal to today’s baseball-watching youth. There’s the cool name, with the two initials blending together to form a single, suave J-syllable; the strange, distinct grimace whenever he throws a pitch; the perfectly bald head. The fact that he is 35 years old and entering middle-age only adds to his universal appeal, as he is neither too young to alienate the old nor too old to alienate the young. And while he might not repeat the kind of dominant pitching performance he had Wednesday, he can be relied upon to be kind of okay most of the time, which, really, is the coolest thing you can be.

When you think about it, really, it’s bizarre that MLB has taken this long to make J.A. Happ one of the faces of the sport. But after Wednesday, Happ’s star power can no longer be ignored. So get ready, baseball fans: We are witnessing the beginning of the J.A. Happ Era.

Yesterday the Seattle Mariners and Texas Rangers played a game of midweek baseball at Safeco Field. Really, it was no different than any other game played on a Wednesday afternoon except for one little detail: it was broadcast on “Facebook Watch” through a new partnership with Major League Baseball which began this season.

The reactions to this new rollout have been slowly trickling in over the first few months of the season, and while opinions vary, complaints seem to coalesce around a similar set of issues: the comments are distracting, why does Facebook need more of my time, it’s hard to get this onto my TV, why don’t you just let me watch my regular team’s broadcasters? All of those sentiments are generally true and I’ll admit, I felt many of them while watching this game.

But despite being of the general opinion that Facebook (specifically) and Silicon Valley (generally) took the absolute wrong message from the Terminator movies, I’m here to argue that you think your problem with baseball on Facebook isn’t Facebook: it’s other people. Other people, you know, who you encounter when you sit in the stands at the ballpark, or ride the bus, or do any of the other things we should be doing in a healthy public sphere both online and off. But this switcheroo is precisely what gives Facebook the ideological clout to distract you from the real, lasting stakes of their ongoing transformation of modern society. You think you hate Facebook because you have to engage with its obnoxious users, not because Facebook dangles freedom and the new to distract you from the fact they know what you are thinking before your brain does.

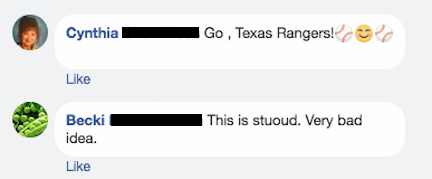

Look at the on-screen comments, for starters:

Here we have Cynthia, who loves her Texas Rangers. Below, Becki, who is showing a little frustration at this stuoud idea to broadcast games online instead of over the airwaves. But is this any different than sitting next to an agreeable dedicated fan on the one side and someone three beers in spitting umpire conspiracies onto the side of your head in the third inning? Heck, sometimes they are fun. I’m not sure who Sharon thinks she’s talking to but,

me too! Or take this:

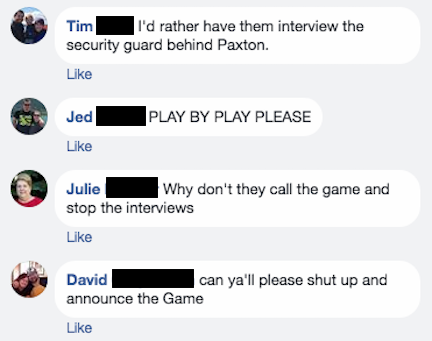

Now what you could do here is roll your eyes at the deluded masses who can’t understand that baseball broadcasts are inherently about conversation, filling dead space with anecdotes in a nineteenth century pastoral game. But that would be foolish, because these people arguably watch the same thing when its on television–you just don’t have to listen to their unchecked stream of consciousness. And you know what? Maybe they’re right! Maybe they go to games in person more often than not, and can’t stand the blabber designed to usually sell products on the radio or pitch upcoming shows on the network.

Perhaps the most telling feature of Facebook’s MLB broadcast is the lack of commercial breaks, wherein they send the cameras down to an on-field reporter, or cut to some local scenery with voice over while a timer counts down:

This is precisely the strange and dangerous part of Facebook, one which seems to be selling itself as a convenient #disruptive alternative to those old forms–loud commercials which so rudely inject themselves into your sensory apparatus from an outdated, more clunky form of capitalism. No, Facebook is here to tell you you don’t need those ads anymore, and don’t worry about how they can afford all this without selling them, just look at the fancy picture.

The future health of the television industry is certainly in question, and with the rise of the algorithm it will only be a matter of time until all our entertainment is consumed through this new unregulated apparatus which already consumes so much of our social lives. But when we combine our desire to simultaneously connect and distance ourselves from those we don’t want to hear with the promise that a kinder, gentler form of monied engagement, we’re opening the door for something much, much more insidious than the differing levels of volume from broadcast to commercial break. Now if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to spend all my discretionary income at the ballpark.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now