By Wednesday, the arugula had drowned. One of the pepper plants sank in its pot, and the basil, larger, more robust, was covered in slugs—the small invertebrate crew of some verdant, sinking Pequod, clinging to their own green mast. The plants themselves had conditions of their own: every leaf riddled with holes, symptoms, surely, of said slugs, or the hail that fell Tuesday. When the first pieces hit the roof, I ran to look for a fallen branch. Only a few breaths later, I saw something bounce where it landed: a pellet of ice the size of a dime. Most were smaller, though, and the shingles seem to be okay. It didn’t last that long. Only the rain.

It didn’t last that long. That’s the kind of thinking I’m doing these days: here, it’s not so bad, and I know it. Elsewhere, it’s worse. In Frederick, Maryland, the storms tore up roads, ruined fields. A high school acquaintance posted Facebook photos of her children helping to save fish that had been deposited and abandoned by the flood waters far from their proper homes. The woman’s own basement was flooded, too.

Elsewhere—just this past week’s elsewhere—more young people were shot at school. Elsewhere, the warming sea chokes in plastics. Elsewhere, a plane crashed. Elsewhere—every elsewhere, all the time—it’s worse, and elsewhere, of course, is a province in the heart, even if in my own backyard it’s only raining. The creeks swell and turn muddy. The sump pump runs. This coming week, if the rain stops, I’ll replant the arugula. This coming week, parents in Texas and Pakistan and Cuba will bury their children. Another glacier will calve.

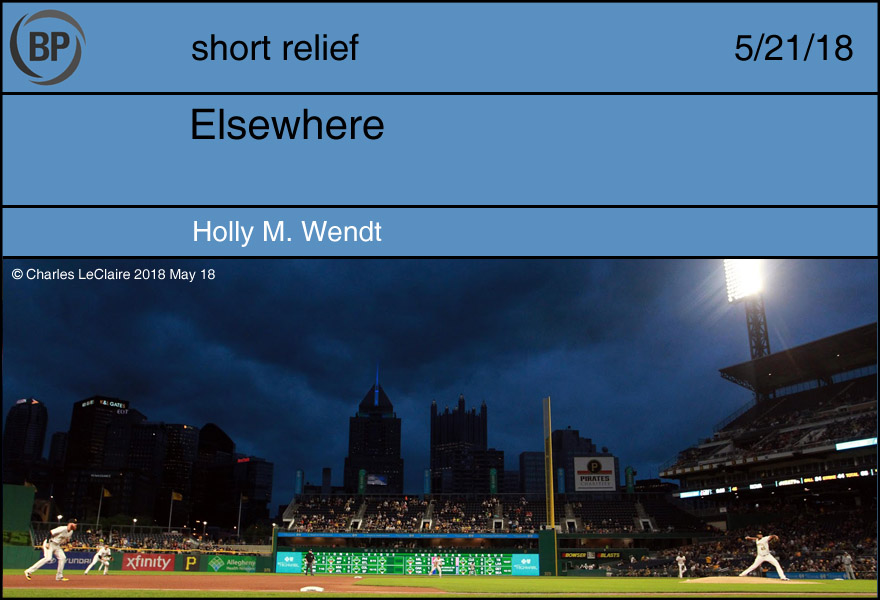

Tuesday night, while storms raked the mid-Atlantic, I waited for a baseball game to start that wouldn’t. It was a week of postponements and delays, and what’s surprising is how many games actually happened, despite the weather, despite everything. What’s more surprising, too, is how glad I am every time it happens, how much it feels like it’s helping, even when it’s not, not in any way outside my own head. One team in gray-and-something pajamas plays a game against another team in white-and-something pajamas and sometimes—more often this year than anyone expected—the team I like more wins. Sometimes I see something I’ve never seen before.

During the Padres-Pirates game on Friday night—watched while waiting out another rain delay—Freddy Galvis’s comebacker got stuck between the fingers of Ivan Nova’s glove. Rather than wrestle the ball free while Galvis pelted to first, Nova tossed the whole glove, stuck ball and all, to Josh Bell for the out. Bell, startled, made the catch, got the out. A minutely charming thing happened elsewhere and also right here—I’m trying to remember that these things, small and good, happen all the time, too, and certainly not just in baseball.

I often feel envy at the origin stories of other people’s baseball fandom: Tales of fathers and mothers and sons and daughters making their baptismal pilgrimages to the shrines of Fenway and Wrigley, coming of age under the arc in the dusk under the fiery arc of a hero’s home run. This is in part because poor memory and parental sleeplessness have conspired to mix my entire childhood into a single sun-yellowed photograph, blurred at the edges. But it’s also because my parents, while faithfully taking me to a ballgame every year or so, never unlocked that passion for sports in themselves.

My mother made me a baseball fan, but it wasn’t because of her love of baseball, but her love of collecting. She gathered and sorted all sorts of objects into little jars: stamps, wheat pennies, screwback earrings, button hooks, cat whiskers. For me as a boy, it began with movie trading cards: In an era before home video, Topps sold trading card sets recapping films like Star Wars. We’d go to the drug store and Mom would buy a couple packs: first Jedi, then Gremlins, a film that in retrospect a six-year-old boy should not have even been watching.

So when baseball cards broached the periphery of my childhood, the progression was natural. It’s impossible to know which exact card was the first, though there’s reason to believe it was this stunning beauty, passed down to me by a well-meaning old neighbor:

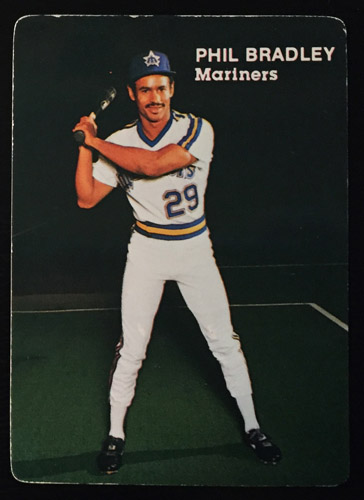

Somehow, I still got to here. Some very light archaeology leads me to believe that my formative baseball card arrived in 1984, slipped into a package of pink-and-white Mother’s brand circus cookies. By the standards of the day, the cards are almost an anachronism, brilliant full-color borderless photographs. But it’s the setting that truly distinguishes the series. The photographer (Barry Colla, who later deigned to appear on his own issue) shut the lights off in the Kingdome and photographed the miserable mid-eighties Seattle Mariners under the shroud of darkness.

I’m barely qualified to plumb even my own subconscious, let alone others, and I sometimes tend to think that we overrate or at least undercount the branching paths that shuttle us along to our final form. But it’s not difficult to imagine a six-year-old Patrick unwrapping the cellophane around this picture of Phil Bradley, the inky black almost just upon him, and thinking: Yes. This is baseball.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now