Three-thirteen. Four-twenty-five. Six-fifty-nine.

I’ve repeated those three numbers to myself like a mantra. Years go by, and still I remember them, in sequence, whenever prompted. Alone, they stand impressive, but together, they stand immortal. Funnily enough, that’s what makes them so tragic.

I didn’t fully comprehend what I was seeing in 2006 when I watched Ryan Howard play his first full season of Major League Baseball. I knew there were reasons to be excited about this looming left-handed launchpad of a hitter based on his torrid half-2005: He hit 22 homers in 88 games and was Rookie of the Year at 26, and had people running the team excited enough that they preferred to keep him and instead offload Jim Thome, whose injury had provided Howard his stage in the first place.

Howard proceeded to hit 58 home runs – a number no one eclipsed afterward until Giancarlo Stanton just last year – while slashing .313/.425/.659. The only other people to do have done that in the last 15 years are Albert Pujols and Barry Bonds. I was awed, and the awful Phillies of my middle and high school years felt more like a nightmare dreamt than a reality lived.

Two-fifty-nine. Three-sixty-four. Five-sixty-two.

I started reading about advanced stats during my undergrad years at Scranton. I became fascinated by BABIP and percentages and the myriad numbers fused to the atoms holding baseball cards together, invisible but foundational. I was seeing the game I had grown up with transformed, in real-time, and it was something akin to whatever Neo must have felt after being plugged into the Nebuchadnezzar and brain-fed jiu jitsu.

But just as Neo began to see his once-real world dissolve into scrolling ones and zeroes, uncovered and raw, I began to look at Howard in a more unflattering light. The strikeouts, the flawed defense, the .259/.364/.562 line across 2007 and 2008 turning my nose up simply as a consequence of being more flank steak than filet mignon. I started to clamor for Howard to get traded. I felt myself enjoying his plate appearances less; I felt more strikeout dread than home run anticipation, and felt more revulsion than exultation when he signed his now-infamous extension.

Two-twenty-six. Two-ninety-two. Four-twenty-seven.

Howard’s final five seasons, almost fully bereft both of joy and healthy Achilles tendons, made it nearly impossible to remember the joy of those earlier days, at first. But it forced me to try to remember them, my mind reflexively enacting martial law and deploying survival instincts as the Phillies regularly lost far more games than they won. It was this decline phase that sent the pendulum back from where it came, and let those old feelings of awe come back in from the cold.

This time, everything was tinged with some regret. I had spent far too much time demeaning and diminishing what should’ve stood as a monolithic achievement, instead of simply allowing it to stay intact, encased in the amber of the past.

In this day and age, with so much effort wasted on telling others why things they like are Bad, Actually, we need to keep sacred all that has given us joy. We’re allowed pleasures without the handcuffs of guilt. Some things in baseball may only be fully appreciated with the passage of time, but everything that lifts us to our feet and fills our hearts need not and should not be sacrificed in the pursuit of further enlightenment. I wish I’d known it then, but I know it now, and I have Ryan Howard to thank for that.

(photo credit: © Bill Streicher-USA TODAY Sports)

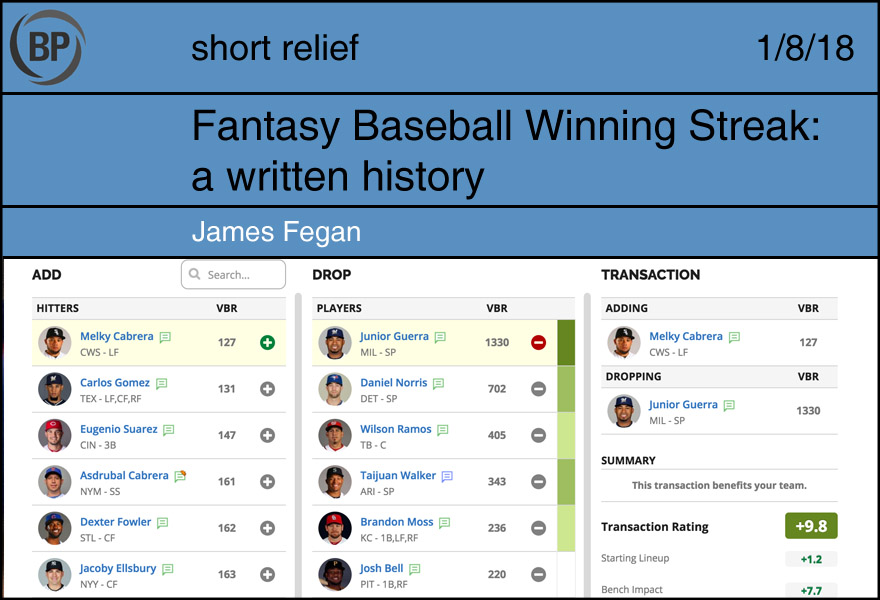

Before Week 1: Fantasy is tedium that I don’t have time for in my busy schedule, but I miss chatting with my college friends.

Week 1: Finally, conclusive proof that I am better than my friend Joe. Feel the lowest shame, Joe.

Week 2: Perhaps I will last this season with my reputation merely besmirched by an embarrassing playoff loss, rather than torched by a losing season.

Week 4: The notion of human equality is a poisonous myth. There are a select few chosen by God to wield immortality like a blade, and now I can feel that cold steel in my hands.

Week 6: A splash text to a dozen work colleagues about my massive lead halfway through the week had a 25 percent reply rate; a clear marker of respect and recognition growing throughout my social circle.

Week 8: It took 90 minutes to recover the would-be festive tone to a reunion of college friends after my commitment to a vulgar celebratory dance proved to outstrip my friend Justin’s desire to be mocked for blowing a 100-point lead on his birthday.

Week 9: “My points against is the lowest in the league because I haven’t played the highest-scoring team in the league—myself!” I pound frantically into the previously unused league forum at 11:35pm on a Thursday. “My strength of schedule is the weakest because I have not played the best team in the league—myself!” I write into a friend’s Slack feed full of baby pictures.

Week 11: All conversations with friends in the league have become stilted and guarded for fear of revealing tactics. Any attempt to socialize with old friends now succeeds in spite of the league, of which any mention inspires feelings of inequity. This league was a mistake and has changed me into a monster hellbent on demeaning people who cared about me. The time I had been spending improving my Spanish is now spent reading injury reports.

Week 12: I cold call my mother to explain the importance of monitoring the waiver wire.

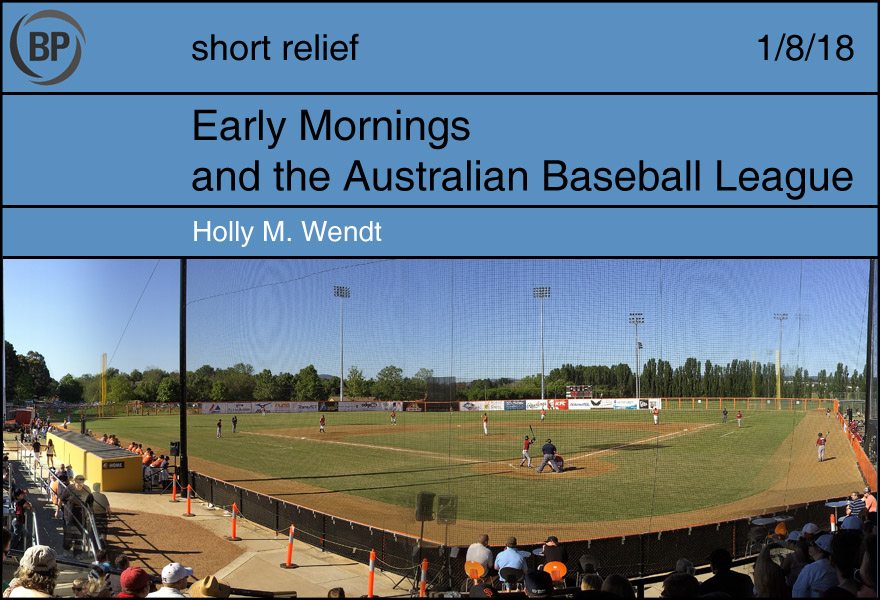

If, on the east coast of the United States, you wake up early enough—or stay up late enough on the west—during these barren winter months, you can catch the Australian Baseball League in full swing. Sometimes, their Sunday afternoon games can carry you through Saturday night.

Six teams populate the ABL, meaning that on any given day, there are three games that could save those wandering baseball-bereft in the northern hemisphere, but the timezone math is a little tricky. Sydney, Canberra, and Melbourne are all in southeastern Australia, luxuriously close together by league standards, and their home games begin sixteen hours ahead of US Eastern Standard Time. Brisbane, though it sits nearly due north of Sydney where the Coral and Tasman Sea meet, is in a different time zone: adjust your planning for fifteen hours instead. Adelaide, on the eastern half of South Australia, poses another mathematical adjustment: by thirty minutes. Fifteen and a half hours’ make that 7:30 p.m. start a 4:00 a.m. alarm clock call. For Perth, all the way across the Great Australian Bight, on the west coast, thirteen hours.

Following the ABL is an excellent way to turn your Northern Hemisphere circadian rhythms upside down, even past the clock-jockeying. While much of the territory covered by Major League baseball teams is under a deep freeze, to look on someone else’s long, hot days, to hear the round, full sound of warm leather striking warm ash or maple while the still-living trees at my window are as brittle as old bone—it’s like looking at a mirage. It was hot enough on Sunday that the broadcast equipment struggled in Sydney:

Please sit tight with the live broadcast of #ABLBanditsSox, the 40+ degree temperatures are wreaking havoc with our equipment!

— ABL (@ABL) January 7, 2018

But then, too, there is other startling news: in Australia, Delmon Young still plays baseball. On Sunday, as DH for the Melbourne Aces, he hit a grand slam off Canberra Cavalry reliever Michael Click. Click, who attended Temple University and has also played seven seasons of independent baseball, most recently with the York Revolution, is still chasing this summer game, hemisphere to hemisphere. Click is a teammate of my favorite baseball player most people haven’t heard of, outfielder David Kandilas. Kandilas made it as far as a short 2014 stint in Triple-A Colorado Springs as part of the Rockies’ system. I watched Kandilas play baseball in Casper, Wyoming, back when the Rockies’ rookie-ball club was still housed there, back when I thought I was far from home.

The ABL is full of players whose names flicker at the edges of one’s MLB-dominated memory: Steve Kent, who rattled around the Braves’ system, and who had a great start against Melbourne this weekend; Ryan Kalish, who played seven games with the Cubs in 2016; 33-year-old Netherlander Loek Van Mil, who spent a decade pitching in the minors, in Japan, in the Dutch Major League, and now in Perth. For some of these players, getting another chance at Major League Baseball feels as close as first base; for others, as far as Alice Springs, on foot.

But that doesn’t matter so much. In Brisbane, the outfield grass is freshly clipped, the baselines newly crisp in Canberra. On a morning in Pennsylvania, still an hour until the horizon brightens, they’re turning the lights on in Adelaide.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now