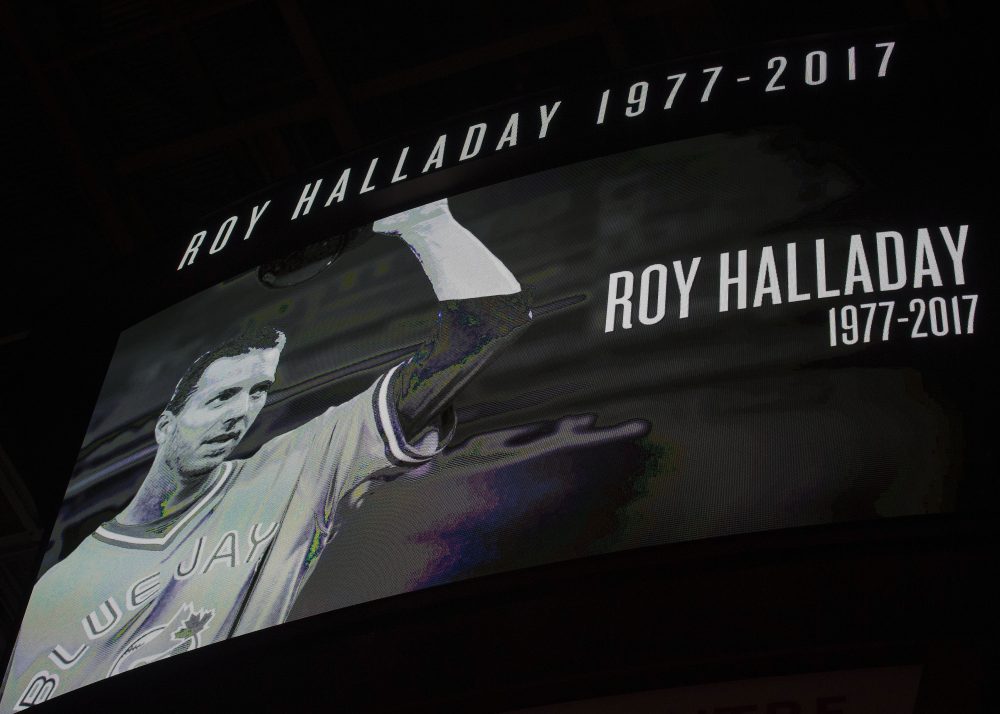

Roy Halladay is gone, killed Tuesday in the crash of the private plane he was piloting, and the living remain to sort out how we will remember him.

The timing of Halladay’s death will not affect the timetable of his consideration for baseball’s Hall of Fame. Halladay is scheduled to be on the BBWAA ballot after the 2018 season—five years after shoulder injuries cut short his major-league career at age 36. The next round of ballots for Cooperstown are due before January 1, which, based on the rules for deceased players, doesn’t give Halladay enough time to be considered in an accelerated fashion.

Following the unexpected death of Roberto Clemente (also in a plane crash) in December 1972, the BBWAA changed the eligibility rules, waiving the five-year waiting period and allowing for an immediate special election in case a player dies. Clemente was elected in March 1973, but the BBWAA amended the rule the following August to make the waiting period six months for deceased players. That’s how it was for Thurman Munson and Darryl Kile, to name two, though neither were elected by the BBWAA.

There was no waiting period yet in 1939, when Lou Gehrig was inducted by a special election—which probably was conducted in part so that he might still be alive to appreciate the honor. The Hall of Fame didn’t hold a ceremony for Gehrig, however, possibly because he would have been too weak to attend due to the effects of ALS. Gehrig died in 1941, and the first waiting-period policy of any kind—for players alive or dead—was enacted in 1946. Gehrig was honored posthumously with a ceremony in 2013.

While he was widely considered to be one of the very best players of his generation when he played, Halladay producing a longer career certainly would have helped to ensure a spot at Cooperstown. He just didn’t have time to put a dignified cap, or a fancy bow, on things.

A two-time Cy Young winner who also finished second twice in the CYA voting, Halladay threw two no-hitters (one a perfect game, and one in the playoffs), and is 40th all time in adjusted ERA, and 24th in strikeout-to-walk ratio.

Halladay ranks 22nd all time on BP’s list of Wins Above Replacement Player (WARP) for pitchers, and his peak compares favorably to a Hall of Famer such as Sandy Koufax, who burned hot, but for not as long as others. Halladay’s peak also shines when compared to that of an active pitcher such as Clayton Kershaw, widely considered the best of his generation today. Halladay does well on the Black Ink and Gray Ink tests, showing like a middle-of-the-road Hall of Famer, and he ranks 42nd all time in Jay Jaffe’s JAWS assessment.

He should get in, and he likely will, though it might not be on the first ballot, for all of the considerable factors. There are no guarantees. Things happen. You don’t have to be Pete Rose, Ron Santo, Tim Raines, Bert Blyleven, Rafael Palmeiro, or Lou Whitaker to know that.

When he retired in 2013, Halladay said his feelings were bittersweet about leaving the game prematurely. Though disappointed and frustrated by no longer being able to pitch competitively, Halladay would appreciate having more time to spend with his wife, Brandy, and their two young boys, Ryan and Braden. Halladay also could occupy himself with hobbies—notably piloting airplanes—and coaching appealed to him.

Halladay later coached his kids in youth baseball and, as a devotee of groundbreaking sports psychologist Harvey Dorfman, he offered his services as a mental coach for the Phillies organization, working with young pitchers to improve their mental approach to preparation. He wasn’t sure about coaching in uniform or managing someday, but Halladay knew that he wanted to be involved somehow, and he was.

Halladay really loved planes, accruing at least 800 hours in the air. Though rated on instruments and multi-engine craft, Halladay died before completing the lessons required to become rated as a commercial pilot, or as an instructor. He wanted to teach his boys to fly. Nor did Halladay have enough time to obtain a psychology degree, to perhaps someday serve as an heir to Dorfman.

Halladay just ran out of time. It is promised to no one, not even the best of us.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now