I will admit to being a little obsessed by hit batters. (This is the second time I’ve started an article with that sentence.) My concern is that they’re climbing because of the rise of strikeouts (don’t look at me like that, just read this), and they’re becoming more dangerous because of high, hard pitches (as discussed here). Given what I view as a growing hazard to the sport, I’m bothered by what appears to be a cavalier attitude toward men being struck by hard objects thrown at high speeds.

One of the more toxic examples is the concept of “protection.” You’ve seen it. A player on your team gets hit, especially a star, and it’s de rigueur that somebody on the other team gets hit. I watch a lot of Pirates games, and the team’s broadcasters practically insist on it whenever Andrew McCutchen gets hit. For a while, Pirates-Reds games were hit-by-pitch-a-rama affairs.

Of course, there are consequences to hitting a batter with a pitch: He gets to take a base. That’s not cost-free. Per our run expectancy tables, the difference between no outs and nobody on vs. no outs and a runner on first is about three-eighths of a run. That’s a significant difference. It may not seem that way in the context of one game in a 162-game season, but it’s something that you’d think would counter the Book of Leviticus mindset that pervades the game.

With that in mind, I set out to test an idea. If there’s an element of hit batters that is, for lack of a better word, discretionary—a pitcher hitting a batter more or less intentionally—we should see less of that in the postseason, when every out and every baserunner is precious. When you need to win four, or three, or one game before the other team does, you can’t (or at least shouldn’t) mess with this Hatfield-and-McCoy nonsense and the attendant baserunners it creates.

I looked at every year in the 30-team era, 1998 to 2016. Over those 19 years, there have been 92,316 regular-season games and 26,202 games with at least one batter hit by pitches. That works out to hit batters every 3.52 games. Here’s a graph of each year.

If the watchword in the postseason is caution rather than vengeance, we should see fewer hit batters. There should be more games per hit batters in the postseason than in the regular season.

Except, there weren’t. In 1,262 postseason games, there were 389 games with batters hit. That works out to hit batters every 3.24 games. That’s eight percent more frequent in the postseason than in the regular season!

But maybe there’s a difference between the teams that play in the postseason and those that don’t. I’m not suggesting that postseason qualifiers intentionally hit more batters than other teams, but maybe their pitchers work inside more, resulting in more hit batters. From 1998 to 2016, the teams that qualified for the postseason played 26,242 regular-season games, during which batters were hit in 7,153 games. That’s a little less frequent than for MLB overall, though—3.67 games per hit batter compared to 3.52 overall.

So for postseason qualifiers, batters are getting hit nearly 12 percent more frequently in the postseason than in the regular season. Let me show you that graphically. Here’s the same chart as above, but with a line indicating games per hit batter in the postseason. If the black dot is higher than the red bar, batters were hit less frequently in the postseason.

Overall, batters have been hit eight percent more frequently in the postseason, as I noted above. Batters were hit more frequently in 10 of the 19 postseasons in the 30-team era.

And for only those teams that played into October:

Pitchers for playoff qualifiers hit batters 12 percent more frequently in the postseason, and in 14 of 19 postseasons.

But how about retaliation? I did the same analysis, but looked for games in which both teams had at least one batter hit. That sounds like it could be eye-for-an-eye stuff, doesn’t it? Maybe the rise in hit batters overall in the postseason is due to strategy and tactics. But countering hit batters makes less sense when you’re desperate to win each game, right?

Since 1998, each team has had batters hit in 3,924 of 92,316 regular season games. That’s an average of once every 11.8 games. Here’s the annual progression:

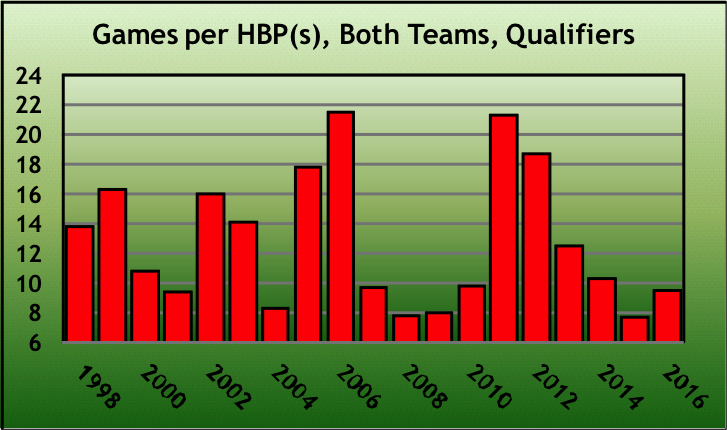

And for the teams qualifying for the postseason, the rate’s a little higher, once every 11.4 games, though it’s pretty noisy year to year:

Do games like this, with players from both teams getting hit, happen less frequently in the postseason? Well, it depends how you look at it.

This chart compares the frequency of games in which players from both teams are hit by pitches in the regular season compared to the postseason. The overall average is almost identical—it occurs once every 11.8 games in the regular season and once every 11.7 games in the postseason. That suggests there’s no difference. Teams are not more likely to refrain from retaliation in the postseason.

But take a look at the black line—the rate of games in which players on both teams get hit in the postseason. The black dots fall within the red bars—the postseason rate is higher than the regular season rate—in only eight of 19 seasons. (There weren’t any postseason games in which players for both teams were hit in 1999.) That suggests that in most Octobers, you’re less likely to see batters from both teams hit.

And how about if we isolate it to only those teams that qualified for the postseason? Same thing:

The years are a little different, but the conclusion is the same: For teams that made the postseason, batters on both teams were hit less frequently in the postseason than in the regular season 11 of 19 years. That’s not an overwhelming majority—it works out to 58 percent of seasons—but it’s something. Additionally, the two-team HBP rate was a little lower overall for these teams as well: Once every 11.7 games in the postseason vs. once every 11.4 games in the regular season.

The message here isn’t an emphatic one. There is some evidence that while hit batters are generally not purposeful, there is a small decline in the incidence of batters from both teams getting hit in postseason games compared to regular-season games. That, in turn, suggests that there are cases of retaliation during the regular season, when the marginal cost of a batter awarded first base is lower than in the postseason crucible. And, with pitchers throwing harder and harder, that’s not a good thing.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

I've seen retaliation consist of a couple of brushbacks, and no real plunking, especially if the umpires get involved and warn/eject the would-be avenger.

Sometimes the target is the next batter up in the next half-inning, but sometimes it's a particular hitter (or the 'offending' pitcher in the NL).

Usually it happens in the next at-bat for the target, but sometimes it is deferred to a later appearance, or even to the next game.

I think you've done a good job of trying to get a general trend, and above all, to prove that there doesn't appear to be a major effect in play. Still, I don't know that we'll ever be really able to model the world of hit batters and their consequences.