We have seen the last of three infielders standing on one side of second base. The infield shift is no longer with us, and MLB teams will have to make do with a 2-2 formation this year. There was a case to be made for banning the shift: that it was dragging the game in a dark direction. The primary effect of the shift was an increase in strikeouts for left-handed batters, as many of them tried to hit the ball over the shift. It also increased walks, and so it took some action out of the game. There was no obvious counter-measure to it, and so the only way to get rid of it was to ban the practice.

But for some folks, the problem with the shift wasn’t what it did to the game. It looked weird. There’s an expectation that fans of a (ahem) certain age have about how the field of play should look. Banning the shift is a way to restore that normalcy. The shift ban was also a statement of intent on the part of MLB. They intervened on a matter of strategy. There had never been rules about where players (other than the pitcher and catcher) could stand, and teams found a way to take advantage of that.

If MLB is willing to strike down strategies in the name of both the way the game is played and the way that the fans expect the game to be played, then MLB might have a few other recent strategic wrinkles that it’s keeping an eye on. The Opener might be next, and it might be next both for the reason that it’s weird and that it’s a sign of the game trending in a way that the game of baseball is trending in a way that league officials don’t like.

Warning! Gory Mathematical Details Ahead!

How common are “openers” anyway? And… what even counts as one? The idea is that an opener is really just an oddball relief appearance, so it would be like asking someone to define a relief appearance. I settled on two possible definitions. Obviously, the pitcher needs to be the first one to take the hill, but I looked for starts that lasted 6 outs or fewer and starts where the pitcher faced 9 or fewer batters. The first definition is going to include some starts where the pitcher had every intention of going 6 innings that night, but just had nothing going right. The second is a little more robust, but we acknowledge that it will include some injuries to a starter early in the game.

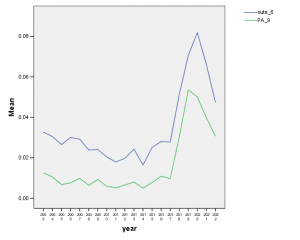

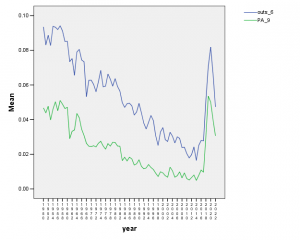

But still, we can see this graph of the percentage of starts that fell into each category by year.

Hang on a second here. I’m having trouble with my graphing program. That only gave me 2003-2022. If you could…

Ah, much better. Surprised? There was a spike in 2018 (and a big shout out to everyone in the Rays front office reading this today) when Sergio Romo started… starting. But going back to 1950, we see that there used to be space in the game for this sort of thing, and back at the time when allegedly, pitchers were so much sturdier.

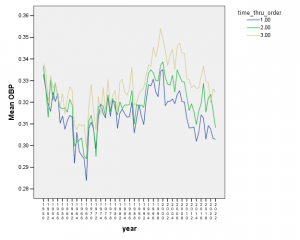

So, why ban the opener? First off, it’s isn’t about the actual opener. The reason that openers exist is worth delving into for a moment. We know that the “third time through the order penalty” is a real thing and always has been. Here’s a graph of on-base percentage, based on times through the order over the last 72 years.

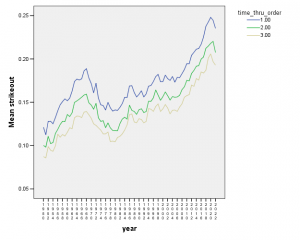

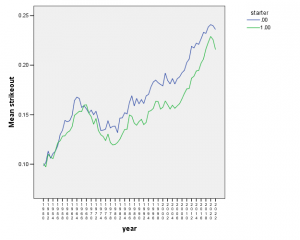

Here’s strikeout rate:

Whether the third time through the order penalty is a function of fatigue (pitchers have thrown more pitches and are more tired) or familiarity (batters have seen the same pitches for the third time), it’s most certainly there. Pair that with the creeping invasion that is the relief pitcher. Since the mid-1980s, relieving has gone from the thing that the “failed starters” did to its own style of pitching. Most relief appearances are short-duration (one inning or less) and usually time-limited. We have “eighth-inning specialists.” There’s not only a time that they come in, but a pre-planned time that they will come out of the game. Relievers are able to “let it rip” a bit more, and the results have literally changed the game of baseball.

That shows the average strikeout rate for starters and relievers over time. Relievers pulled away as they became more specialized, and as more relievers came into the game, the tipping point where it made sense to go to them during the game moved further forward. The average start used to be six innings not even a decade ago. Now, it’s barely five.

With enough relievers, teams can strategically say “We’re not going to allow our pitcher to get to the third time around.” That comes with a cost. Over 18 batters, a starter might only throw 60-70 pitches. They’ll still need four days of rest to recover, but they could probably throw 30 more pitches if you needed them to. The advantage of the opener is that it allows a manager to insert the “starter” an extra inning or so later into the game. They can then go through their 18 batters. When batter number 19 comes along, it will be one of the ones a little further down the lineup and the game will have had a little more chance to reveal itself. It’s possible that the situation will allow the starter/follower/bulk pitcher to go a little further.

That’s why you use an opener.

The problem isn’t the opener. It’s that the game is being pushed toward a model where the starter is being marginalized, and more than that, where tired starters—who don’t strike as many batters out—are being replaced by relievers who do. There’s a case to be made that starters are used in a style that is much closer to relievers. They have a pre-set job. It’s a longer job, but it’s just a job, and their job isn’t to get through “as much of the game as possible.” It’s to provide “enough coverage” to get the game to the relievers. The opener is just the most visible manifestation of that. The “starter” doesn’t even start the game.

When MLB banned the infield shift, they fortunately had second base as a clean line of demarcation. The new rule says that teams need to have two players on either side of second and all of them on the infield dirt. Teams have also been shifting in the outfield, or at least positioning their fielders better, and if MLB wanted to ban those outfielders from roaming around, they’d probably have to draw chalk circles in the outfield. To enforce a rule, you have to have a boundary. That hasn’t happened in the outfield yet, but it’s probably because there’s no real natural boundary in the outfield. The reason both that the shift looked weird and the reason that it was easy to ban was that second base was already an unofficial boundary in people’s heads before it was etched into the rulebook.

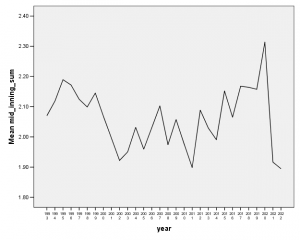

In the same way, there is no rule about when a pitcher can or can be taken out. At least, there isn’t for the starter. MLB has already put into place the three-batter minimum for relievers. It was supposed to cut down on the number of mid-inning pitching changes per game, although…

The only way to get rid of the parade of relievers would be to kill the octopus. Most bullpens have eight arms, so there are a lot of pitchers who can join the parade. MLB has quietly set a limit that teams may carry no more than 13 pitchers, but if they wanted to ratchet it down, it would force teams to be more judicious in how and how many pitchers they used each day. Some would have to get out of the one-inning mode.

But still, even if we can’t fight against the oncoming hordes of relievers, we can at least restore the traditional optics of the game. We might not be able to fight progress, but we can make it look like we haven’t lost it.

We need a rule that we can easily enforce and that discourages teams from trying to use an opener. The thing about the opener is that it’s really just a reliever being used in a weird order. If there’s something that we know about relievers in the modern game, it’s that the majority of relief appearances last three outs or fewer. Multi-inning relief appearances are rare, and once you get to a third inning, it’s not really even an opener any more.

So, let’s make a rule that says that the starting pitcher must throw three innings. Oh, but what happens if the starter is getting shelled? Or gets hurt? What if the team has every intention of sending a “real” starter out there and… well, some nights, you just don’t have it, and you’ve given up 8 runs in 1.2 IP? We don’t want to leave teams stranded if they put a starter out there in good faith. We can modify the rule to say that a pitcher removed before three innings may not enter one of the next four games for that team. If it really was a start that went haywire, then that pitcher wasn’t coming back for a few days anyway. But the point of the one-inning wonders out of the bullpen is that often, they can come back the next day. Teams would think twice if using an opener meant losing that reliever for most of the rest of the week.

Much like the infield shift, we need to think about not just the effect on the gameplay, but also how the game looks. Fans of a certain age have come to expect two infielders on either side of second and a starter who at least makes some attempt to get past the sixth inning. Or the third. It might very well be that a shifted infield or an opener is actually an evolution in the game. We usually reward people who come up with ways to innovate within the rules to give their team a better chance to win, but we can’t allow that if it means that the game is going to look different than it did 40 years ago.

And so, let’s ban the opener.

***

When you say it out loud like that, do you realize how silly it all sounds?

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now