Despite what you may have heard, the starting pitcher is not dead. This season will be remembered as the year of The Opener, Bullpen Day, and the Great Starter Fakeout of 2018, but the starting pitcher is the same as he used to be.

When we talk about how starting pitching (or anything in baseball) is changing, it’s important to understand how we got there. That way, in a few years when The Opener becomes standard practice, we’ll understand what went on. And we also need to dis-entangle (as much as we can) a few strands of the “starter is dying” narrative from each other. In some sense, openers and bullpen days and the third-time-through-the-order penalty are all related, but it’s important to understand why.

Warning! Gory Mathematical Details Ahead!

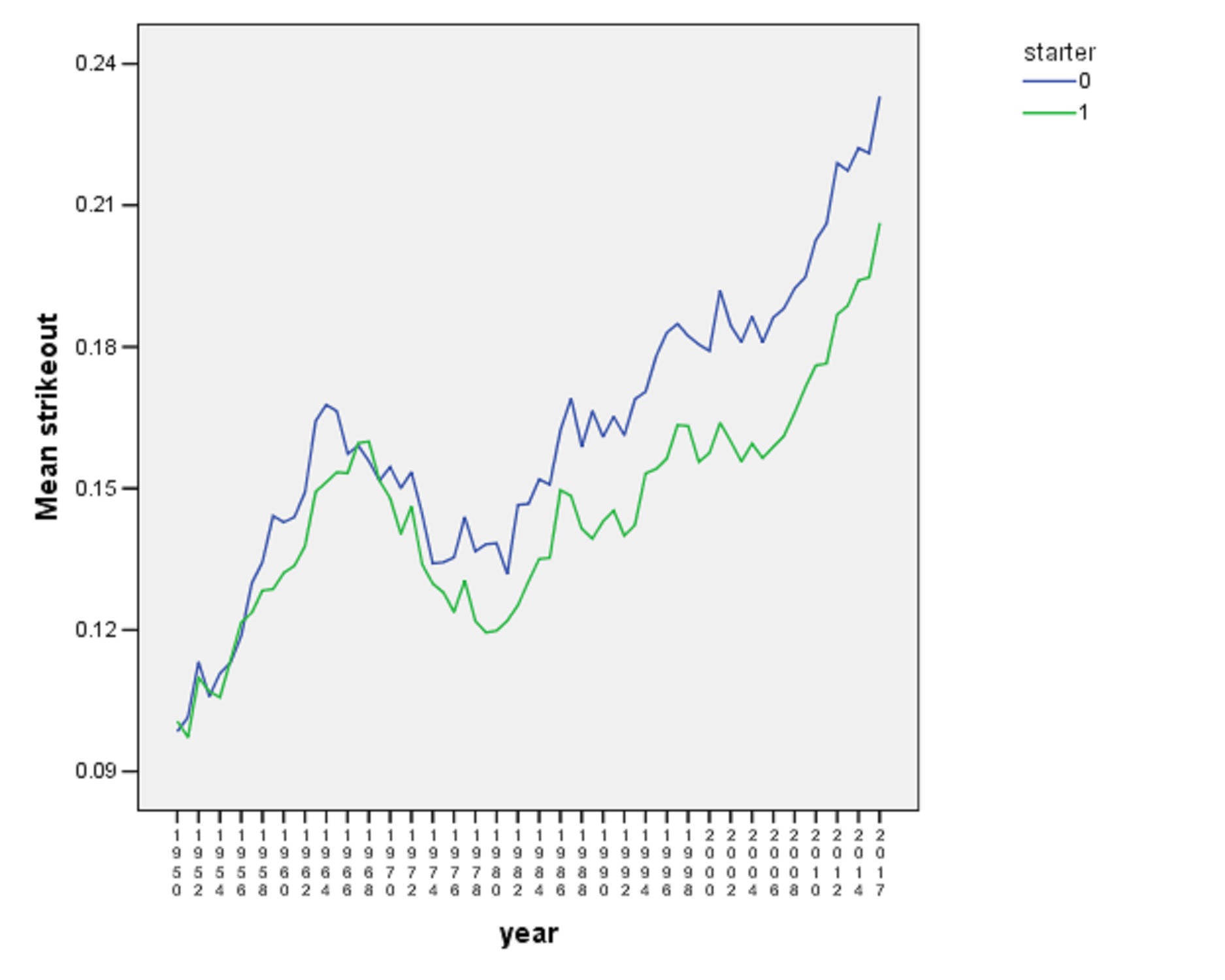

Let’s start at the beginning. We need to talk about the development of pitching roles going back into the 19th century. The idea that pitchers always went the distance in ye olde days is a myth. By 1922, more than half of starts ended before the game did, but for the most part relievers and starters were interchangeable. Most pitchers did a little bit of both, and the results weren’t all that different in either role. In fact, here’s a graph of the overall strikeout rate (K/PA) for pitchers in the starting role and in the relieving role from 1950-2017. (I’m using Retrosheet data, and that 2018 data set isn’t out yet.)

We only begin to see separation around the late 1960s/early 1970s. This was the era in which we began to see specialized relievers who weren’t just “starters who happened to enter in the sixth inning.” The rate at which pitchers did “a little of both” had been dropping at that time as well.

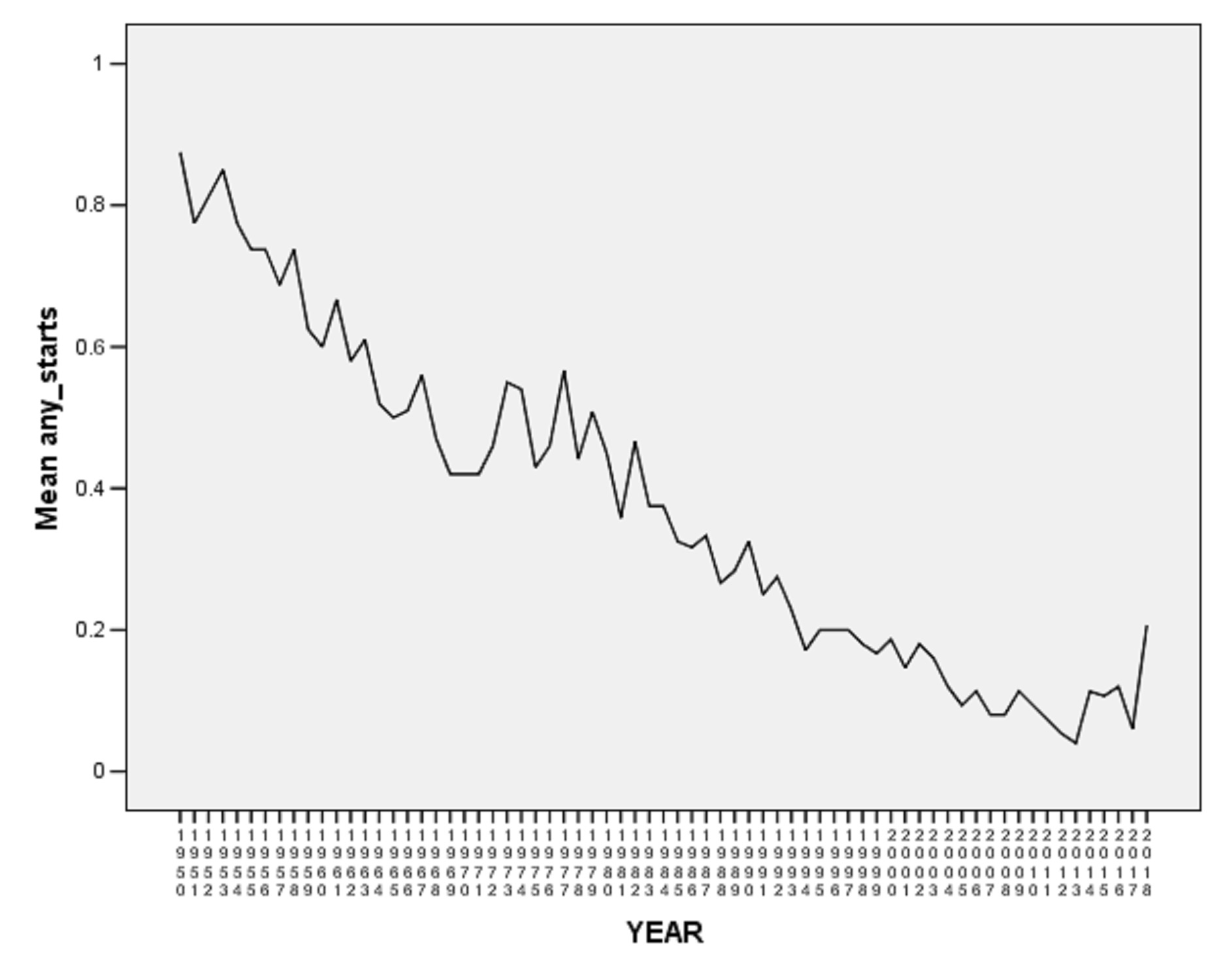

Here’s a chart showing, by year, the percentage of relievers who notched at least 70 innings in a year who made any starts in that same season.

In the 1960s and 1970s, we entered the realm of two types of pitchers: starters and relievers. It’s worth noting that it took about a century of baseball history to get to that point.

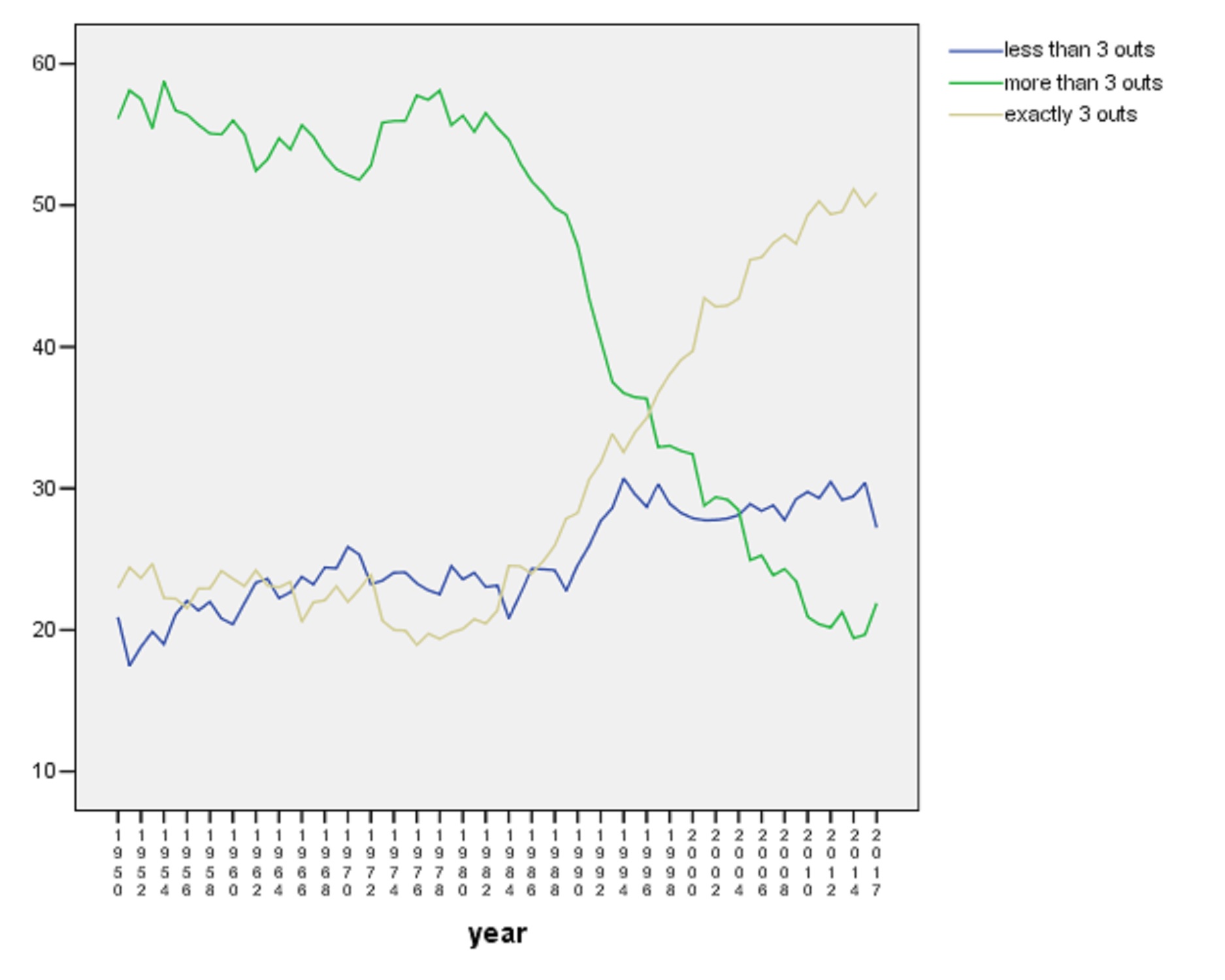

The next era of specialization came in the mid-1980s when the “one-inning reliever” role was solidified. Below is a graph, again by year, of the percentage of relief appearances that lasted less than three outs, more than three outs, or exactly three outs. Around that time, the line representing multi-inning relief appearances began a 20-year journey to switch places with the line representing “exactly three outs.” Again, it’s worth pointing out the timescale. The two lines cross in the mid-1990s.

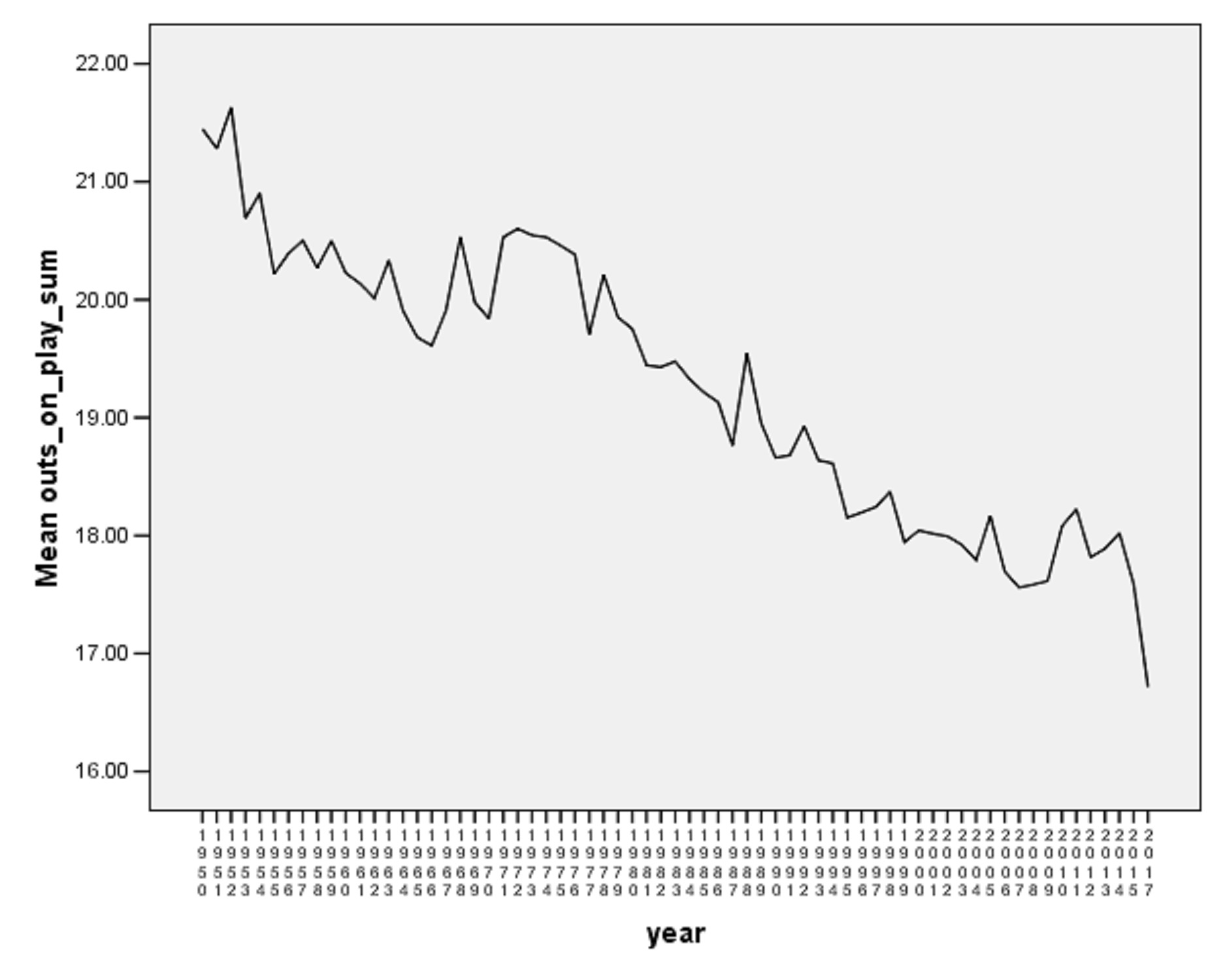

At the same time, there was another well-documented (and lamented) trend among starters. Starting pitchers have logged fewer innings per start over the last 40 years. From the mid-70s until 2015, there was a slow decline in which the average starter dropped about 1.5 outs from his workload. From 2015 to 2017, they dropped just about as much. That’s not a lot, but it’s something. Today’s starters don’t seem to have the same staying power as the old ones did.

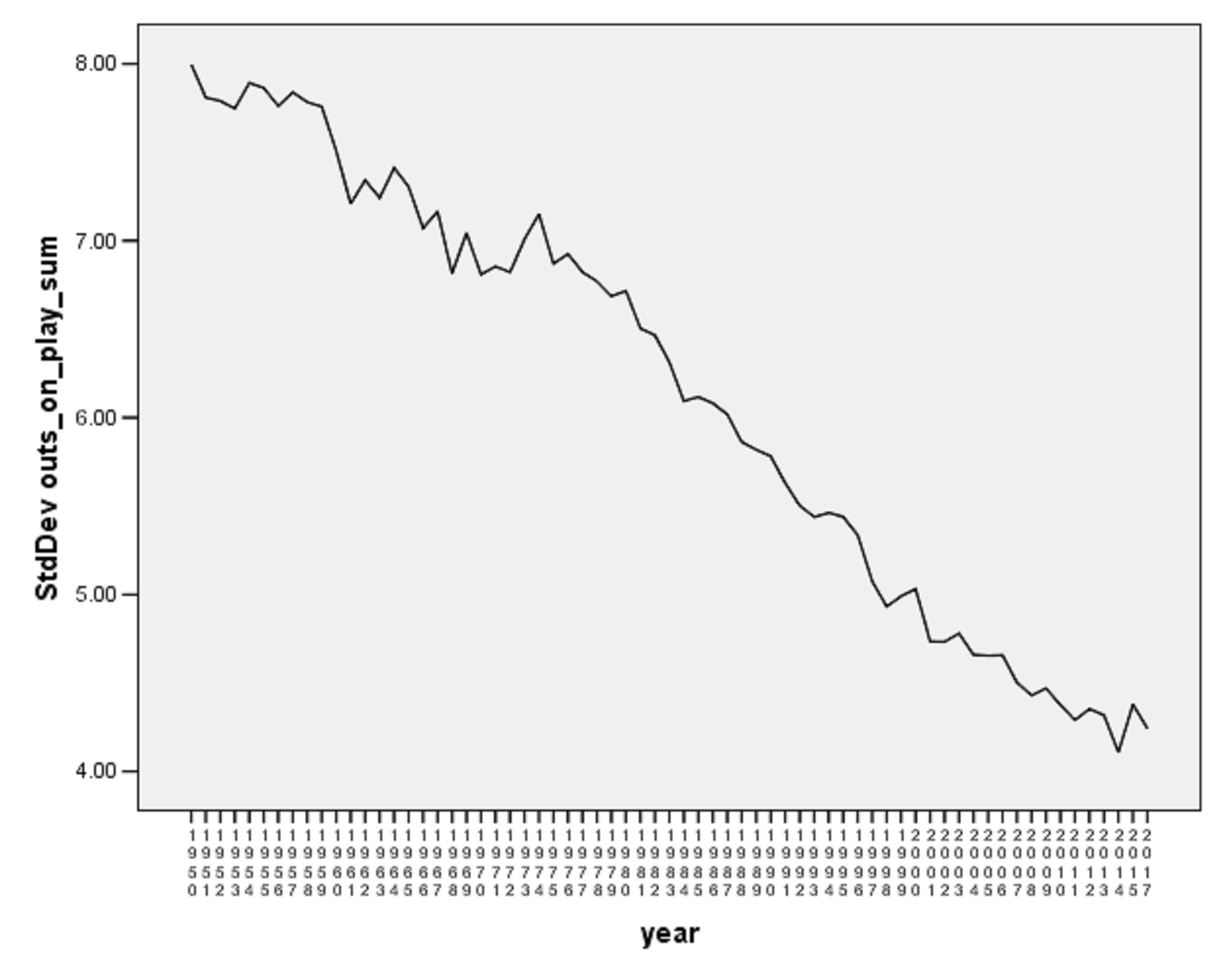

Or was that really what happened? It’s true that starters pitch to fewer batters and record fewer outs on average, but as I used to tell my intro to stats class: “If mean, then standard deviation.”

Here’s a graph of the standard deviation of the number of outs recorded by starting pitchers as time has marched on. There are plenty of people longing for the days when there were pitchers around who never … left … the … game. While those guys were out there, the graph below shows the real story was that the job of “starting pitcher” used to be a lot more varied than it is now. Indeed, “the starter” has become so solidified as “the guy who goes five or six innings” we’ve forgotten it’s legal to go three innings, if that made sense for the team. There used to be slow-hook guys and quick-hook guys. Now, we might still use those terms, but they don’t denote the same (wide) amount of variation.

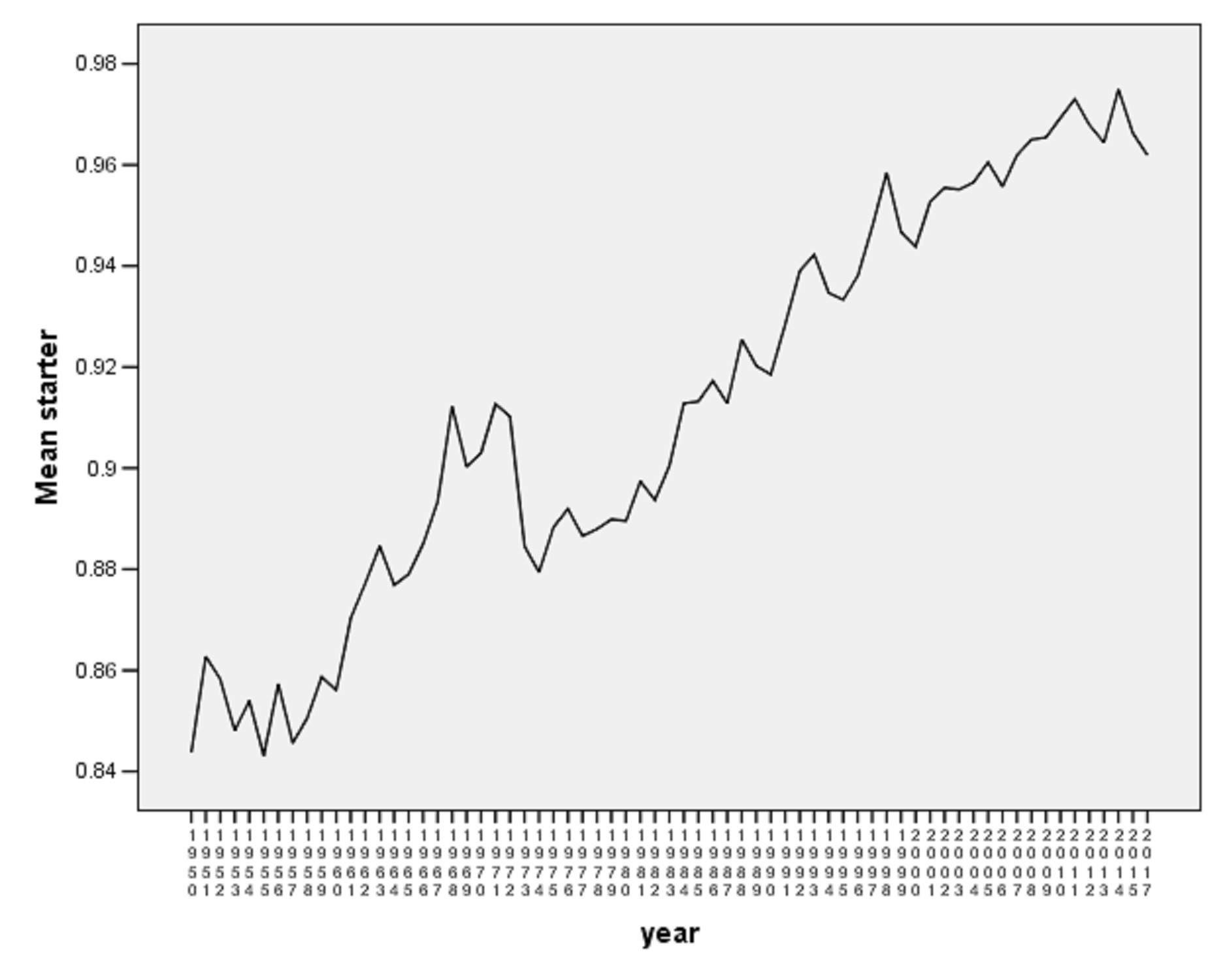

The entirety of baseball pitching history to date has been an evolution from generic “pitchers” to two highly specified, highly calcified roles. There were starters and there were relievers. The starter’s job was to provide bulk innings. The relievers were there for one-inning stints. A manager was supposed to lead off with his bulk guy and then see how the game unfolded before deciding which of his relievers would enter. I don’t think people ever appreciated how deeply ingrained the idea that the first guy on the mound had to be the bulk guy was. In fact, if anything, that norm has become more cemented over the years.

Here’s a graph over time of how often a team’s starter (i.e., the first person on the mound) was also who got the most outs.

The idea of the “bulk out-getter” being someone other than the first pitcher on the mound is actually an older idea. In the 1950s, about one in six starters saw a teammate get more outs than they did. By the turn of this decade, it was down to about one in 30. Some of that is a tribute to the evolution of the one-inning bullpen pitcher—even if a starter flames out after the third inning, his replacements are likely to be one guy who throws two innings and then four guys who take a frame each. In the 1950s and 1960s, as specialized relievers were only beginning to evolve, teams carried what would now be called “long relievers” who would pitch multiple innings.

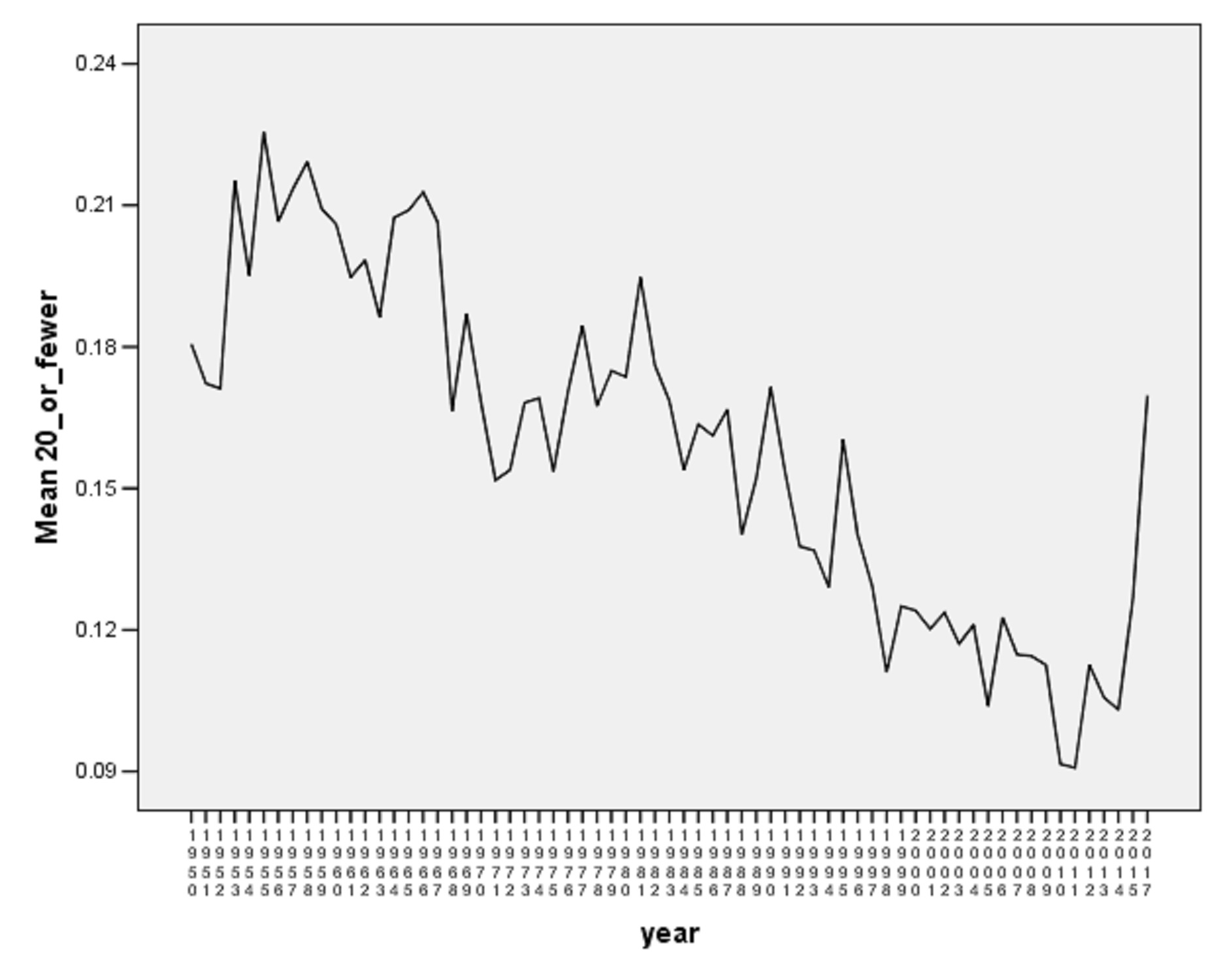

But there’s more to it. The big idea supposedly driving the new pitching order in baseball is the third-time-through-the-order penalty (TTOP), and the corollary that managers should have a quicker hook on the pitchers who aren’t as good, because by batter 19 they are fighting both their own lack of talent and the TTOP. It’s supposedly a giant revelation, but …

Above is a graph of the percentage of starts in which the starter faced 20 or fewer batters (twice through the order and maybe a “one or two more batters” kicker). We see that spike at the end in the present day and think it’s a new idea. We lack the historical perspective to know that we’re simply returning to older times. There have always been quick-hook guys and slow-hook guys. It was the modern game that tried to shove them all in one box.

***

As teams inevitably embrace the idea of the slow-hook guy and the quick-hook guy (or the three-times-through guy and the two-times-through guy), we’re going to see a proliferation of openers. The modern pitching staff was built on the assumption of 5-6 innings from the starter, and when a pitcher is told he’ll be leaving after 18 hitters it probably means he’ll be pitching significantly short of that. The system will have to compensate. Some of that will be in the form of relievers trained to throw more than one inning on purpose. Some of that will be in the form of having another TuTO guy around, at which point you’re having a tandem starter day or a bullpen day (take your pick).

But some of it will be compensated for by the opener. When a team has identified one of its pitchers as a twice-through-the-order guy (a TuTO), then it’s a simple matter of logic that they should use an opener. TuTOs, somewhat by definition, aren’t going to record as many of the 27 outs as a ThreeTO would, and that’s going to put more strain on the bullpen. However, if they’re what’s available, then it’s best to plan for what you have rather than what you wish you had.

The logic behind The Opener (and here, there should always be a reflexive thank you to Bryan Grosnick for laying the theoretical groundwork) is that a team can probably identify one of its “going to pitch anyway” relievers. And if a team is serious about not letting a pitcher get to a third trip on the merry-go-round, they already know who the “going to pitch anyway” reliever is going to face anyway. From the perspective of “getting outs,” he can record those outs in the first inning or in the fifth inning, but by doing so in the first he gets the “bulk guy” to a point where he starts on the fourth or fifth hitter in the lineup.

This way, when the manager gets to the 19th batter the bulk guy faces, it’s in the lower half of the lineup. The manager also has more information about how this game is going, to the point where he can then make a better decision about whether he’ll keep his TuTO out there a little longer to effectively act as his own bridge reliever. If the score is 9-3, why not let him go another inning and save the bullpen a bit? The Opener allows a manager to have more information at his fingertips about a key decision he’ll have to make. Other than “it doesn’t look as weird,” there is no advantage to not using an Opener.

It will eventually stop looking weird.

The reason we’ll have a glut of openers soon is the same reason we’ve had any sort of strategic breakthrough in the game. There are ways we’ve been trained to think of the game that aren’t actually true. Over 50 years of pitcher usage, we slowly grew to believe there was only one sort of starting pitcher, and we were taught things about when and how long they could pitch. We were lulled into thinking things had always been this way. They hadn’t.

And yes, there will be plenty of complaining about The Opener and how it supposedly disrespects the foundational commandments of the game (and how things were different in the 1970s). What’s funny is that The Opener is actually a riff on an idea from 50 years ago, updated somewhat to account for the realities of the present day. You just need a little bit of historical perspective to understand how and why it happened, and that in some ways it’s a case of “nothing new under the sun.”

The starter isn’t dead. We’ve just (re)discovered their actual nature. There are two types of starters we’ve been trying to fit into one box.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

I guess that doesn't really help with the "Starter" vs "Bulker" question, though. Maybe there will be a category for Games Opened? Or maybe Games Started just doesn't matter any more?

Flash forward to the present day. Even an ineffective starter "has to get his work in." Starter are nor usually removed in the 2nd or 3rd inning. Instead, they struggle on for four or five, trying to keep the game close. Now, there are no short starts or complete games, just a lot of pitchers going 4 0r 5 (if ineffective) or 6 or 7 (if effective).