It’s astonishing that a division can contain both the Mets and the Marlins and a team that used to be the Expos, but they contain five distinct city flags. Hope you like stripes.

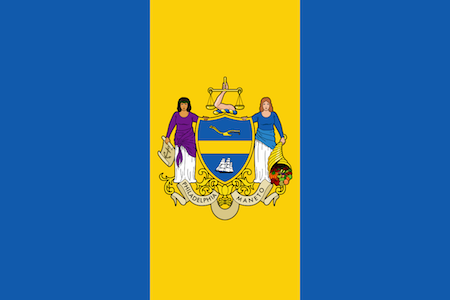

Philadelphia

The operative question is, is this the Gritty/Phanatic of flags? We start with the flag of Barbados, a vastly underrated Caribbean island, and removed the trident — a rough start. But they’ve replaced them with two vibrant fans, one with a horn o’ plenty (no whiz), held like it’s a cudgel. The other has a map of the best places to find horns o’ plenty. We have a severed arm of unknown origin and cause. We have no idea what’s going on but we love it. This is chaotic enough.

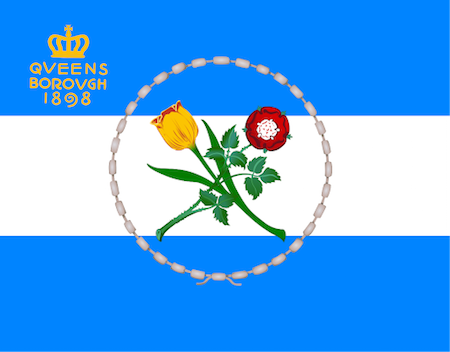

Queens

We already covered New York in the AL East, which brings us to the Queens flag, which is not officially recognized in part because it needs revisions, namely something other than a circle of wampum, as well as a typo in their city name. But more jarringly, the two flowers because of Wilmer Flores and I still don’t have the heart to tell them that he no longer plays for the team. Although in many ways he still is a Met, just on a different team. Just like every other ex-Met. The “9” in 1898 looking like it’s going down the drain? Pure coincidence, and there is no joke there. Especially since they just hired a baseball manager with no known scandals.

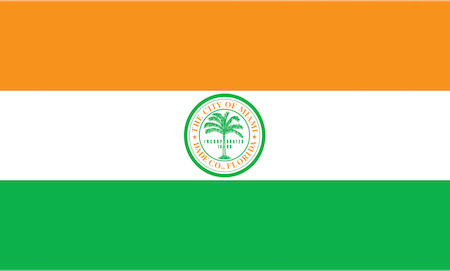

Miami

“India but with palm trees” is a heck of a look since India, which already has palms, is just Miami with infrastructure. A lack of pastel means Miami’s design basically usurped the ideas of others and executed them worse. That, or they took their unique concept flag and traded it away years ago.

Atlanta

Nothing can be truist truer than minimalism, which in this case, is a blue backdrop and the avian home plate umpire calling Sid Bream safe.

Washington, DC

The historical context: this was the Washington family coat of arms. The recent context: this is a Five Guys cup. The stars are technically called “mullets,” which is a shame for a team whose history has featured none, unless you count the Expos, which we do, in which case they’re honoring Randy Johnson three times. Otherwise we’re stuck with expanding the term to include Jayson Werth, and that’s a gross mischaracterization of the term mullet. It’s the first flag I wouldn’t mind seeing turned into an alternate jersey, because sometimes you dodge the barbs of humor when you’re a team that just won the World Series and instead get a compliment. So if this paragraph didn’t end funny enough, blame the Astros for not cheating harder.

My favorite number is 17. Has been since middle school, or I guess whenever that moment in my life where it was decided I must have a favorite number was. I chose 17 because it’s different but still mainstream enough to be cool. It’s not flashy like 1 or 7, rather it’s an understated combination of them both, which is why it rules.

Only two MLB teams have retired the number 17, which feels low for what is clearly the best number. The Cardinals, one, for Dizzy Dean, which is fine because as a Reds fan I dislike the Cardinals and didn’t want to play for them anyway, and the Rockies for Todd Helton.

Growing up a baseball fan in Tennessee, I knew three things about Todd Helton. One, he started at quarterback for the University of Tennessee over Peyton Manning for three games, basically sacrilege in the state. I found it absolutely hilarious. “The best quarterback of all time backed up a baseball player,” I would tell my friends when they tried to clown on baseball, saying it wasn’t a sport or or whatever teen boys say to emasculate other teen boys. They never had a great retort.

Two, I knew that Helton absolutely eviscerated the Reds. It felt like every time, no matter how bad the Rockies were, Todd Helton would sweep into town, take one look at Reds pitching, and laugh. In 95 games, Helton hit .323 against the Reds and had an OPS of .945. For context, a full season of that mark in 2019 would have ranked him 11th, between Juan Soto and Pete Alonso.

And the Reds weren’t even the team Helton feasted on the most. He recorded better career OPS numbers against 11 other teams, hitting over 1.000 against seven of them. In fact, Helton’s career OPS of .953 indicates, almost imperceptibly, that he was not even his average self against the Reds.

And three, I knew Todd Helton kinda looked like my dad. Not in a way that’s readily apparent, but in the same way that Jeff Fisher kinda looked like my dad or the way any prominent Tennessean with a mustache/goatee combo kinda looked like my dad. Todd Helton kinda looking like my dad didn’t matter of course. But it did make me like him a tiny bit more.

All of which is to say, Todd Helton belongs in the Hall of Fame. In part for his myth: a franchise face, a one-teamer, a man who started over Peyton Manning. In part for his performance: a prolific hitter, a five-time All-Star, a man who struck fear in opposing pitchers even when he wasn’t his best. In part just sheer irrationality: I love Todd Helton not for his performance but for sentiment.

And Todd Helton played 17 seasons. That’s a big plus. 17 seasons isn’t flashy like 20; it’s understated. It shows consistency to a brand. It shows commitment but not a rigid adherence to round numbers. In short, it rules. Way more than 29% does.

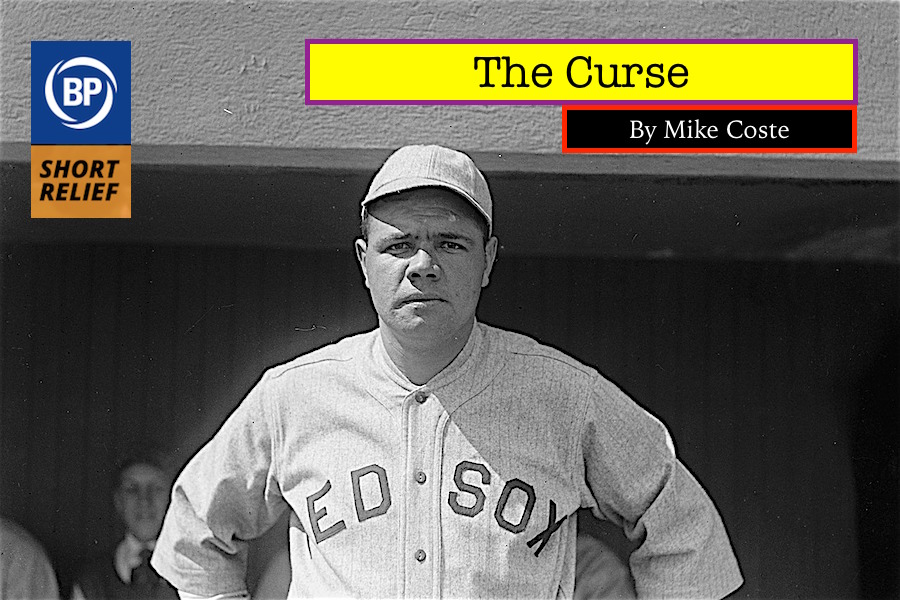

If there is anything worse than undergoing suffering, it is watching someone you love suffer. I experienced this pain growing up watching my father. Since this is ultimately a story of redemption, I can write about it now. It was something that was passed on to other family members that I was fortunate to escape. You see, growing up, my dad was, and still is — a Red Sox fan.

I remember seeing great Boston teams, teams that looked like they were destined to win the World Series, sputter out, in some cases spectacularly. The Red Sox had not won a World Series since 1918. From that time, well before my father’s birth, to the end of the twentieth century, the Sox had fielded legendary teams, with equally legendary close losses. Hall of Famers Ted Williams, Carl Yastrzemski, and Jim Rice had played their entire careers in Boston, hitting home runs, appearing in All Star games, winning Triple Crowns, and not one of them had a World Series ring.

It was hard, growing up, watching my dad’s cynicism turn to hope as his beloved Red Sox appeared to finally be headed toward victory, only to see them dashed as they managed to lose yet again. The low point was the legendary 1986 World Series in which the Red Sox were up three games to two over the Mets. Having scored two runs in the top of the tenth, the Red Sox were one out away from winning the game and the Series. Three singles and a wild pitch later, the game was tied, and then lost on an error by Bill Buckner. Their fate was sealed when the Mets won Game Seven and the Series.

It was clear to me after that the Red Sox were doomed inevitably to blow the big games, and my dad, like so many others would never see a Red Sox World Series victory in his lifetime. I later learned that this tragic state of affairs was no fault of my father, or even Bill Buckner, but instead was the result of the Curse of the Bambino. As legend has it, the Babe was upset at the Red Sox for selling his contract to the Yankees (to finance a Broadway play, no less) that he put a curse on the Red Sox that they would never again win a World Series. The Fates had spoken, and, like Sisyphus, the Red Sox were doomed to continuously come close to reaching their goal, only to face the inevitable disappointment.

The 2004 season appeared to be a better than average, although still unspectacular one for the Sox. After starting off slowly the Bosox managed to make it as a wild card team.. After sweeping the Angels, they faced the New York Yankees. Mercifully, the Yanks won the first three games. Never had a baseball team come back from being down three games to none in a best of seven series. And then it happened. In a miracle finish that turned the tables on their usual luck, the Red Sox swept next four games and made it to the series. Leaving no room for doubt, they then went on to sweep the Cardinals to finally win the World Series. The curse was broken, and my dad can now proudly display his Red Sox pride as they have won twice more in ensuing years.

So what happened? I like to think that Ted Williams, having passed during the 2002 season, had gone to baseball Valhalla to face the Babe. His revenge was exacted on Ruth’s own Yankees as the Bambino could not hold his own against Teddy Ballgame. The Curse was vanquished.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now