“Not everything that is acceptable in moderation should be tolerated in the extreme. As fans, we cannot bargain with the players or ownership, we cannot write the terms of the CBA. We cannot enact a fix to the problem of teams intentionally fielding a lineup that isn’t their best because they’re incentivized not to. We can stop providing cover for these actions just because those incentives exist.”

I wrote those words in September of 2018, about teams manipulating the service time of prospects, and why it was an ethical failure. They might as well have been written today, about Astros or the Red Sox and their use of technology to steal signs. Where the manipulation of service time is in a grey area of the CBA, though surely in bad faith, using technology to steal signs is an explicit violation of the rules. And still, it has its defenders:

To excuse as “borderline unreasonable” the idea that someone who had to choose whether to break a rule to get ahead would opt not to do so is a disservice to the millions of people who operate within legal, ethical, and moral parameters every day. It’s a slightly altered version of the admiration on display when people congratulate Uber for failing to operate within regulatory bounds simply by having the audacity to declare themselves not something which they clearly are.

It’s an extension of the logic that pervades both business and sports alike, a logic that removes culpability and responsibility from those who act and places them instead on the structures in place. Structures are, of course, a part of the equation, but incentives are not mandates. Our decisions in the face of perverse incentives become the qualities that define our characters as organizations, corporations, and people.

We must be able to separate the rationalization of an action from a judgment of it. It’s not difficult to figure out why the Astros broke the rules as it pertains to technology and sign stealing, nor why the Red Sox are alleged to have done so. They share Alex Cora in common, but also a paranoia that others are doing the same things and by not doing them, they’re falling behind. In MBA terms, they viewed their actions not as differentiators, but as qualifiers within the market. They had to behave this way just to keep up, you see. Again, it’s not hard to understand. It’s also not hard to avoid condoning. The rules are there, plain as day, reiterated by the commissioner multiple times over the course of the various infractions.

***

On Monday afternoon, the league handed down year-long suspensions to General Manager Jeff Luhnow and Manager A.J. Hinch, and levied a fine of $5 million against the organization. Major League Baseball also removed a first- and second-round pick in both the 2020 and 2021 drafts. Subsequently, Astros Owner Jim Crane fired both Luhnow and Hinch. Commissioner Rob Manfred noted that the Astros culture within the baseball operations department, in particular, had led to both the incident in which Assistant General Manager Brandon Taubman verbally abused three female reporters, and to the conduct described within the report:

Finally, I will make some general observations regarding the Astros’ baseball operations department that were gleaned from the 68 interviews my investigators conducted in addition to the nine interviews conducted regarding a separate investigation into former Assistant General Manager Brandon Taubman’s conduct during a clubhouse celebration. Like many Clubs with very experienced individuals running their baseball operations departments, Astros owner Jim Crane and his senior executive team spent their energies focused on running the business side of the Club while delegating control and discretion on the baseball side to Luhnow. And it is difficult to question that division of responsibilities in light of the fact that Luhnow is widely considered to be one of the most successful baseball executives of his generation, credited with ushering in the second “analytics” revolution in baseball and rebuilding the Houston Astros into a perennial Postseason contender. But while no one can dispute that Luhnow’s baseball operations department is an industry leader in its analytics, it is very clear to me that the culture of the baseball operations department, manifesting itself in the way its employees are treated, its relations with other Clubs, and its relations with the media and external stakeholders, has been very problematic. At least in my view, the baseball operations department’s insular culture – one that valued and rewarded results over other considerations, combined with a staff of individuals who often lacked direction or sufficient oversight, led, at least in part, to the Brandon Taubman incident, the Club’s admittedly inappropriate and inaccurate response to that incident, and finally, to an environment that allowed the conduct described in this report to have occurred. The comments in this paragraph relate only to the baseball operations department. This aspect of our investigation did not extend to the business side of the Club that functioned independently of baseball operations.

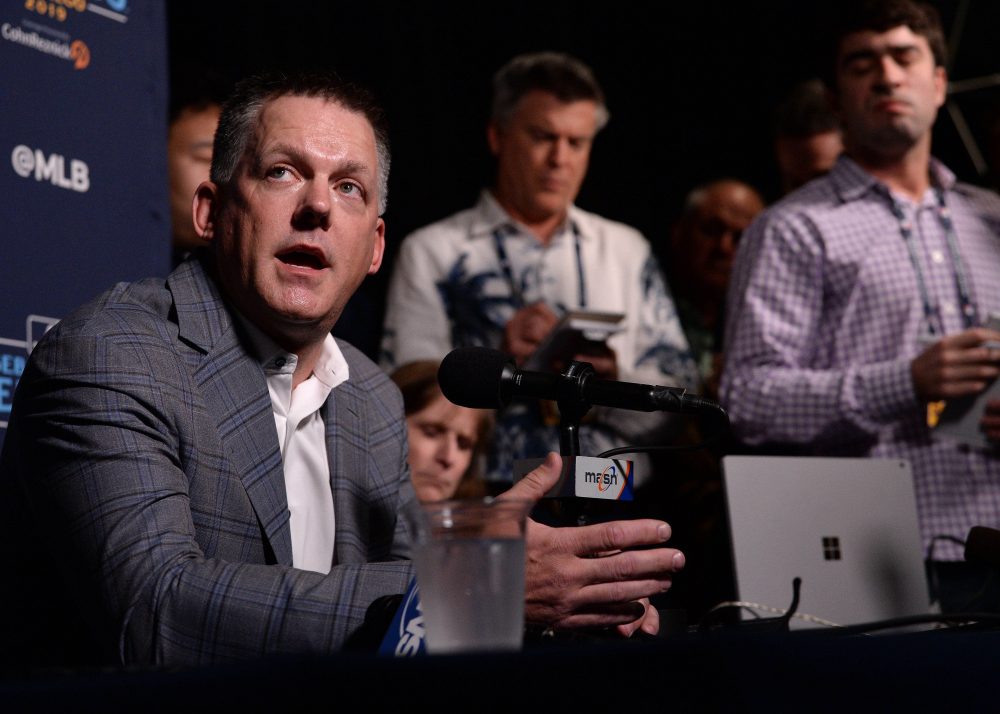

This portion represents the most thinly veiled anger within the commissioner’s report, and it is also the section on which Jim Crane pushed back the most during his press conference. He disagreed with the commissioner’s assertion that the culture was the issue, though it’s worth noting that he said this in the midst of firing his manager and general manager.

Culture is a nebulous concept, often used as a catchall for the intangible aspects within an organization, the secret sauce that allows people to flourish or alternately the most plausible explanation for an ineffable failure. Hazy as it may be, culture has profound effects on the people who both compose and participate in it. The Astros organization prided themselves on process during their losing years, but later repeatedly demonstrated their belief that the ends would justify any means. In fact, one could argue that this was the root of their culture.

***

One common complaint toward ethics is that they’re malleable and can change over time. Ignoring that this is the case with laws, standards, best practices, morals, and ethics alike, it’s also a feature, not a bug. That we can, as a society and culture, update our ethical guidelines is a positive. It also means that we’re responsible for enforcing the ethical boundaries that we want to see persist throughout generations. We can neither capitulate to efficiency and optimization, nor default to a mindset of “what’s ethical is what’s legal.” There are too many unaddressed aspects, grey areas that people are willing to mine for the sake of a dollar in terms of the latter, and too many people who will be exploited—willingly or not—in the case of the former.

Beyond which, ethics are the basic underpinnings of our legal frameworks. Take the time to look up how many legal documents, doctrines, and concepts are grounded in and require “good faith.” We rely on the notion that the person across the table isn’t signing this contract or agreeing to this deal with express purpose of reneging on it. Similarly, any system that has “fair play” at the basis of it relies on the idea that all are entering with a willingness to abide by a code of conduct. Releasing bad actors from that code of conduct because their violations are “rational” isn’t acceptable. We must continue to aim higher with our ethical expectations as a means to reinforce and undergird the existing infrastructure. Without them, it will continue to crumble.

There’s a level of individual responsibility inherent in all of this. Each choice we make is a demonstration of character, and demonstrations of character drive our understandings of cultures and subcultures, both the ones we observe and the ones in which we participate. It’s empowering, and also depressing, since clearly someone can simply opt out of all personal responsibility to justify some other end. To some, this is a means to discredit the idea that our society can function this way, disregarding the fact that our country, our world has evolved over time in exactly this way. The Astros’ top management chose to replace their principles and values with a fetishization of winning, of efficiency, and value of a different sort.

As liable as Astros management may be, the players cannot be absolved of their role in this process. As with the teams themselves, many players felt compelled to cheat because they assumed their opponents were doing the same—both sides unable to conceive of acting in good faith. The commissioner’s report repeatedly mentioned individuals who understood what they were doing was wrong, but were waiting for someone else to tell them to stop. They knew right from wrong, ethical from not, and failed to act.

***

Naturally, the commissioner disagrees, to a point. He opted not to punish the players involved in sign-stealing, despite the schemes being “player-initiated” and “player-driven.” The reason for this seems to be two-fold, per the report: 1) Manfred indicated in his prior statements that further punishments would fall on management if additional infractions occurred, and 2) that discerning culpability between the numerous players who were involved in the violations, many of whom were no longer on the Astros, and then meting out a just punishment was a logistical nightmare that he didn’t want to take on. Left unsaid was that involving current players would likely invoke grievances and appeals from the Players Association, ones that would drag the scandal out longer and crack the veneer of the “harsh” punishment he delivered.

Indeed, the league’s actions are as self-serving as those of the players, managers, and GM in this situation. It was difficult to watch Jim Crane discuss the lack of action from Luhnow and Hinch without wondering what to make of the guy conducting the press conference with “owner” as his title.

So, too, with Manfred. Reports have long indicated, with specificity, that the Astros were engaged in this behavior. With the prior sign-stealing violations in place, the commissioner had to be aware of the situation. Ultimately, he chose not to act, not even to investigate, until it was blown wide open via The Athletic’s reporting with former-Astro Mike Fiers on the record. Manfred correctly identified the Astros’ culture as a significant factor in what led to both Taubman’s incident and its repeated, self-inflicted denials and in what led to this craven opportunism from and organization that had otherwise been held up as a league standard. He also correctly evaluated that both Luhnow and Hinch, as key management personnel, were responsible for that culture. What he failed to do, though, was extend that line of reasoning to its logical endpoint: If Manfred truly believes that those at the top of organizations are responsible for the behavior of those below them, he might want to look into who is responsible for the actions of the 30 teams that compose Major League Baseball. Seems to be a bunch of ‘em breaking the rules.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

They all had to know about it. Manfred needs to show a little more leadership (guts). I suggest all the active players from that team should be fined 5% (pick your amount) of their salary this season regardless of the team for which they now play. You do the crime you get punished.

It would be so much easier if they were wrong, but they're not. And there are so few people with the expertise needed to understand how those things are pursued or how competition is conducted at that level, and those are often the exact ones you would need to catch the cheating in a concrete way. There is the 'everyone knows everyone's doing it' video room stuff, in this case, but then there's more esoteric, complex, and likely more effective stuff: is there a team running a machine learning algorithm on these video feeds? to analyze signs more rapidly? to incidentally find pitch tipping that might be imperceptible to the human eye while they're at it? To find more effective and yet more discreet means of communicating the information? To zoom and enhance viewing on the pitcher's hand in the set position, or in the glove, to straight up identify pitch grips?

All of this stuff is possible, and it's probably barely scratching the surface: There are things that only the people at the cutting edge of this abuse can even conceive of, and they're the only ones who would catch others doing it. They're the only ones who know what to look for; the ones who know which of those ideas sound good but don't work, and which things sound absurd but really do. Those are the best exploits - the ones that your opponents would dismiss if they heard about them, but actually work for some reason.

I don't know what the solution is. I don't have any faith that we can get a majority of humans to behave ethically. We can criticize, we can punish when we find it, but I think there's a degree to which Alden's fundamentally correct. Not from an ethical perspective, or in a way that we should excuse it, forgive it, or look the other way, but that we should realistically expect it and look for it. We should give noone the benefit of the doubt. If you are succeeding at the very top end in a cutting edge, cutthroat, hyper competitive environment, you're pushing the rules. It's the only way to succeed in that kind of environment. It's how you differentiate yourself from the folks in the middle. It's the difference maker. Dodgers? Yankees? Brewers? Cubs? Athletics? Twins? Every single one of them deserves our skepticism. It is necessary.

But I don't think we'll catch them - or most of them, anyway. We lack the expertise, and the only people who can catch them are the ones who know how the game is played - the ones who are doing it themselves. And that knowledge is perishable, as the cutting edge will move if they stop participating.

Unfortunately, this kind of cheating isn't actually the existential threat to baseball the way that software hacking is to the software industry, so expecting it to induce such radical change is unlikely.

In most endeavors like this, you know the cutting edge folks are operating in the gray - finding the holes in your rules, finding unanticipated (and therefore, not forbidden) but fundamentally unfair advantages, and other ways of getting ahead. It's built in, and the shades of gray vary, but they all fall into that same sort of classification.

Then there is the explicitly forbidden stuff. What the Astros did here falls into that category, even at the time, but has since had that line made even more clear. By defining what is explicitly unacceptable and making the individual costs for excursions over the border unacceptable risks, one can often constrain folks to the gray area. Then you have a simple battle of loophole closing/rules generation opposed by innovation. I don't know that that dynamic is fundamentally unhealthy, and I think it is the closest thing to healthy that we see in those kinds of hypercompetitive environments. Unfortunately, because the tools are so similar (would a live algorithm watching for pitch tipping be legal, but sign analysis not be legal? I think, per the letter of the rules, that this is actually the case. But if you were doing one, it requires no further effort to do the second), you have a substantial moral hazard by placing people in a situation where adding the illegal thing to the borderline thing requires no further effort (signs/pitch tipping are again a great example: the pitch tipping occurs in exactly the downtime between your analysis of the sign and the actual pitch, so you are naturally watching that period anyway, so why not do both?)

That's the kind of situation that's most prone to abuse (which is why we'll probably learn that a majority of MLB teams have done something inappropriate with their video rooms at some point in the past). If MLB can clearly define some boundries and make it clear that the consequences for getting caught on the wrong side of them are personally catastrophic and career-ending, they might be able to keep folks in the gray areas. Then all they have to do is identify anything that becomes toxic and widespread and define it outside the border.

I don't know that that really gets you a more ethical environment, but it at least gets you a manageable one.

I guess it was too much to expect Manfred to slap Crane on the wrist with the same one year suspension, as Crane is one of 30 men who have the power over Manfred’s job. He can’t go around ticking off any of them, as the can create coalitions to get you of you, as Faye Vincent learned.