Thetis, the mother of Achilles, gave her son a choice: he could live a short life filled with glory and become famous for ages to come, or he could live a long, boring life and die unremembered. He chose the former and was, of course, killed by Orlando Bloom as we all remember from that classic of modern cinema, Troy. I promise, we will get to why this is important.

Now normally, a team hiring a new bullpen coach would fall beneath my notice. It’s not a high profile position, after all, falling somewhere between head trainer and groundskeeper on most fans’ radars.

But when the Twins promoted Bob McClure to be their new bullpen coach last week, I took notice. For one thing, because I remember a bunch of sweet-ass baseball cards from the ‘80s featuring Bob McClure’s sweet-ass mustache game, which was very much on point. But, for another, it’s because Bob McClure has been around forever.

He was drafted in 1973 by the Royals and debuted for them two years later, tossing 15.1 scoreless innings in his first stretch in the Majors as a reliever. He pitched on those great Brewers teams at the start of the ‘80s, even spending some time as a starter. But, for most of his career, he settled in as a perfectly good left-handed reliever, and lasted 19 years in the big leagues. After finishing his career as one of the original Marlins, McClure went into coaching and has been more or less continuously employed as a pitching coach or bullpen coach ever since.

He is another in a long list of data points supporting my theory that, if you’re a pleasant enough person, you can work in baseball for as long as you want if you’re either A) a catcher or B) left-handed. That there is some kind of magical wisdom projected onto those two demographics that, when combined with a general affability, makes them virtually eternal fixtures within the sport whose careers last far beyond their physical ability to compete on the field. Like good wallpaper they are not particularly noticeable, are just there in the background of everything.

I know I’m not supposed to feel this way, but this, friends, seems like a good way to live: well-liked enough that someone will always want you to be part of what they’re building but never so prominent you’re the target of somebody’s ire. We are supposed to be ambitious and leave our marks on this world. We’re supposed to burn out, rather than fade away.

But being a decent guy with a lot of insight seems to provide a wellspring of continuous opportunity for guys like McClure who may lose one job but fall quickly into another because they’re loved and respected. They will not make the Hall of Fame, but will get to be around the game they love for 40 or 50 years and go out on their terms. I would choose it in a heartbeat, if only I were left-handed.

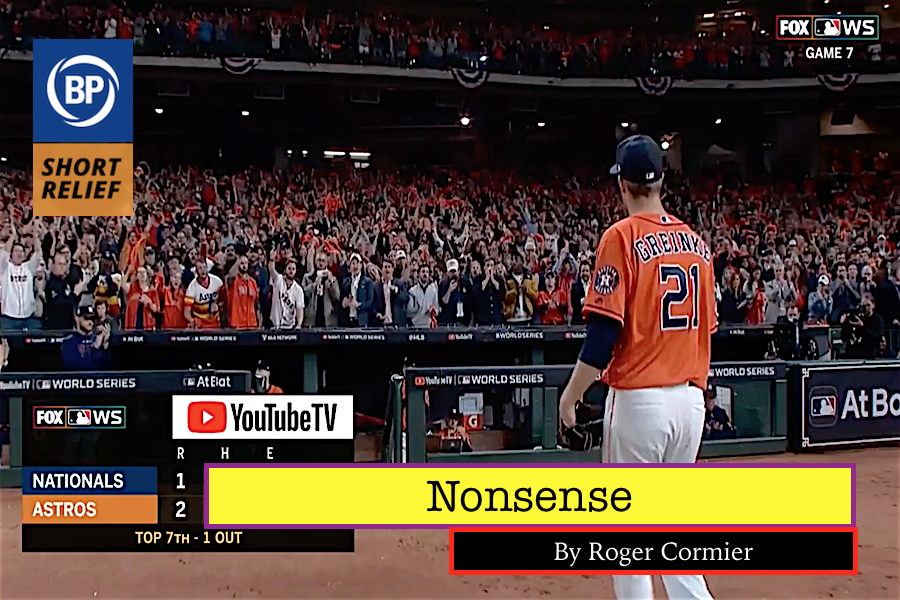

There was a World Series Game 7 only two and a half months or so ago. Zack Greinke was one of the starting pitchers that night. I honestly don’t blame you if you forgot – there was plenty going on involving Greinke’s team right before and soon after.

Greinke pitched well. After six innings and 67 pitches he only let two Nationals touch a base. Only one got as far as second, and that was because of a silly bunt. He convinced Adam Eaton to ground out to start the 7th inning. It was 2-0 Astros. Eight outs away. Then Anthony Rendon homered. Greinke refused to give Juan Soto a chance to hit a game-tying blast in a winner-take-all for the second time that month, so he politely let him have first base. Then A.J. Hinch told Greinke it was time to leave and let the bullpen handle this, and then the bullpen immediately dropped the expensive vase.

I watched the game at the same Lower East Side bar where I took in Game 7 of the 2016 World Series. I wanted the Cubs to win then, yet also for Aroldis Chapman to screw things up. That worked out! The only snag was when the bartender from Shaker Heights shut off the TVs seconds after the final out and punched the ceiling. Since he was no longer employed there I figured I’d go to the magical establishment again. I decided I wanted Zack Greinke to do well but for the Nationals to win. I ended up having to explain this to, from what I remember, the only three other customers that night — all from the D.C. area. They weren’t sports fans but were definitely supporting their hometown , and I said that was fine — the Nationals were not the participating team that employed Brandon Taubman and took an eternity and a half to apologize to Stephanie Apstein after calling her a liar for accurately reporting on Taubman’s behavior, after all, but I wanted Greinke to do well since he suffers from social anxiety disorder. One of my new friends seemed far more intrigued by this new bit of information than the other two. As Greinke walked towards his dugout after the 6th she said “Aw, he’s not looking up at the crowd.” When Greinke did look up as he made his exit in the 7th, she noticed that too. I felt like the three D.C. folks at that moment thought I was a liar. I considered explaining he’s been taking Zoloft for almost 15 years, and it’s not like he has to actually talk to the 41,168 people in the building, but that would come off defensive, among other things.

Maybe I should have brought up 2004, when Zack was told he was getting the call to the big leagues, and his first response was to ask if instead he could start over in Single-A and try to come up as a shortstop, and that to this day his minor league manager still doesn’t know if he was kidding or not. Or February 2006, the spring after Greinke’s disappointing first full year with the Kansas City Royals, when he could not concentrate during a bullpen session and didn’t throw a single strike. How he walked away from baseball after that day for two months to get diagnosed and medicated. How even when he first came back to the organization he notably kept saying how much he enjoyed Double-A Wichita. How he once said he wished he knew about Zoloft before then. How he hasn’t talked about his condition at all outside of three interviews as far as I know, and I wish he would talk about it more, but it was probably hard enough for him to talk about it at all in the first place. It was probably enough when he explained it this way:

I don’t know a good way to put it — it’s having anxiety every day. It’s not fun. I wouldn’t call it painful, but it’s definitely not enjoyable.

This paragraph from the Los Angeles Times based off the one time Greinke addressed it as a Dodger was also helpful, personally:

He said that’s one of the reasons he signed as a free agent in a giant place like Los Angeles. He doesn’t mind being watched by crowds. It’s the close personal encounters that bother him.

How I think it’s sad he seems to regret the first time he acknowledged it:

“It’d probably be more of a hassle than anything,” he said, referring to the added attention it would bring. “Just [like] the Sports Illustrated article. A bunch of nonsense comes with it. I don’t think about no-hitters, ever.

How everyone focused on the part when he sort of said he would rather not throw a no-hitter, even though he’s basically right, no-hitters aren’t special anymore, and they aren’t a true measure of a pitcher’s greatness. It’s just that you are not supposed to say that.

How it seems that most of his former Dodger and Diamondback teammates like him, and not just because he was really good at his job, making their jobs easier and more fun, or because the bar was so low after players assumed he was a loner and it turned out he would actively help them and inquire about their personal evolutions as ballplayers, but because he’s apparently Larry David. Before a big Dodger game in 2013 he stood up and said to the entire team:

Some of you guys have been doing the number two and not washing your hands. It’s not good. I noticed it even happening earlier today. So if you guys could just be better about it, that would be great.

They won that night. This is what Jake Lamb had to say about Greinke:

If he didn’t want to talk to you, he just walked away or said, ‘I don’t want to talk to you.’ I love that guy.

Maybe I should have clumsily said I understood why some people act like Greinke, how what other people might think or will say paralyzes some people so much they have to completely shut down the part of the brain that deals with the feelings of other people, and to some they come off as major jerks. Some save their time and energy to only those they have to deal with on a daily basis. As Alex Avila conveyed to Zach Buchanan, some work on it, even if they don’t have to:

We were on the bus and it was one of the first road trips last year, just a few weeks into getting to know him. I remember saying, ‘Zack, from what I’ve heard, you’re sometimes tough to get along with. What changed?’ He said, ‘Yeah, I don’t have many more years of playing, so I figured I’d work on my personality.’

I didn’t bring any of that up. Now three people think they met a liar in New York last October, because they definitely remember me and always will. I wish I didn’t say anything at all in the first place. Bunch of nonsense.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now