Search for “Cody Bellinger” “batting stance” and you’ll find some quotes about offseason adjustments. His legs were too straight. He stood too tall. That sort of thing.

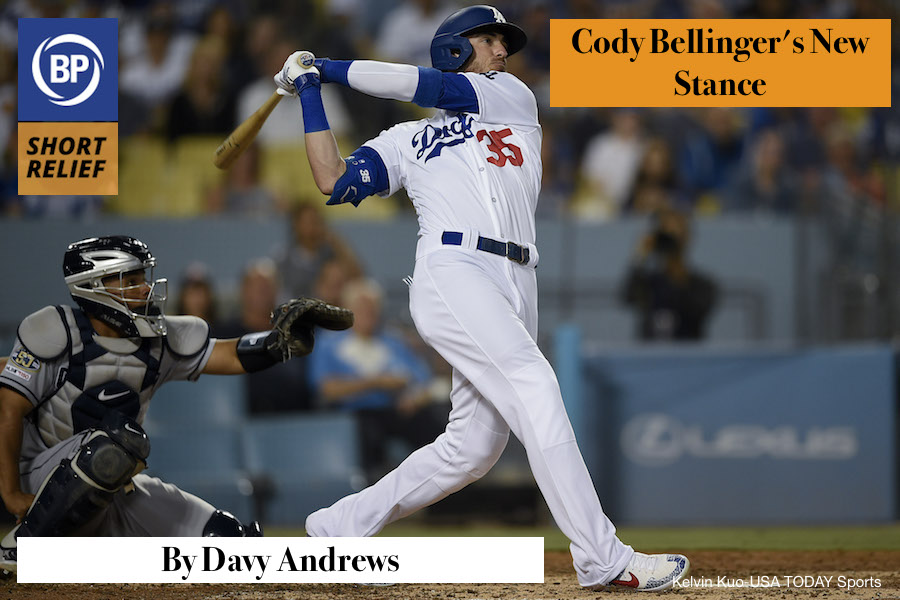

And it’s true. He stood tall with his legs straight: feet even but torso rotated slightly toward the catcher, so he had to peek over his shoulder at the pitcher. Hands high, elbows high, bat angled up high. So tall and high and altogether altitudinous, in fact, that he peeked over his shoulder and you’d swear he was looking down at the pitcher.

Like tension, is what he looked like. A cobra about to strike. I’m looking at a picture of the old stance right now, and what keeps running through my mind is the way William Goldman describes Inigo Montoya in The Princess Bride: “Blade thin, six feet in height, straight as a sapling, bright eyed, taut; even motionless he seemed whippet quick.”

But I didn’t search for “Cody Bellinger” “batting stance” to look at the old one. I wanted to look at the new batting stance. The one he’s using to OPS 1.098, to lay siege to the Triple Crown, to topple empires and annihilate galaxies.

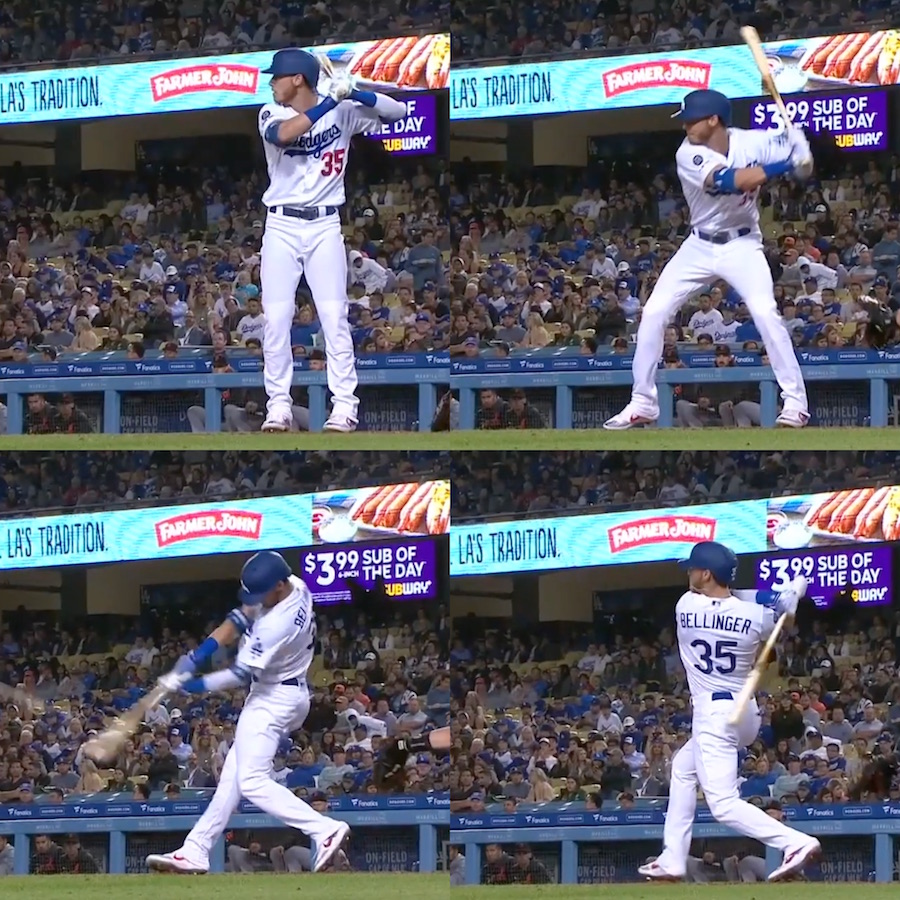

I have to tell you, he no longer looks like tension. That’s why I did the search in the first place. Because he’s not taut. He’s not about to snap or crack or twang like a bowstring. His legs are bent a tiny bit and his stance has opened up. The bat is still high, but now it is parallel to the ground. His elbows are just regular high and his back is just regular straight, rather than so straight that he is actually bending slightly backward.

Looking at a picture of this stance, he reminds me of the city slicker you see in the movies who is been asked to split some firewood. He looks like he is about to swing an ax, but he is not all that sure how to swing an ax.

Maybe Cody Bellinger looks more relaxed than he did last year, more balanced, more controlled, but he also looks less dangerous.

And sure—then the pitch comes and the bat snaps up and he’s lithe and he’s potent and he leans in and strides and clears his hips and the particles that once constituted a baseball leave a vapor trail from Chavez Ravine out to Proxima Centauri and my God, talk about dangerous—but I like that first part. Where he’s just standing there. Where if it weren’t for the bat and the uniform and the stadium, you’d see his posture and think he was maybe just a little pissed off. Like he was trying to get into the bank to use the after-hours ATM, and he’d already swiped his debit card four times but that godforsaken light on that godforsaken card reader just would not turn from red to green, and he was taking a second to regain his composure and decide whether all this was even worth it. That’s the part I like.

I wanna have pride

Like my mother has

Not like the kind in the Bible that turns you bad

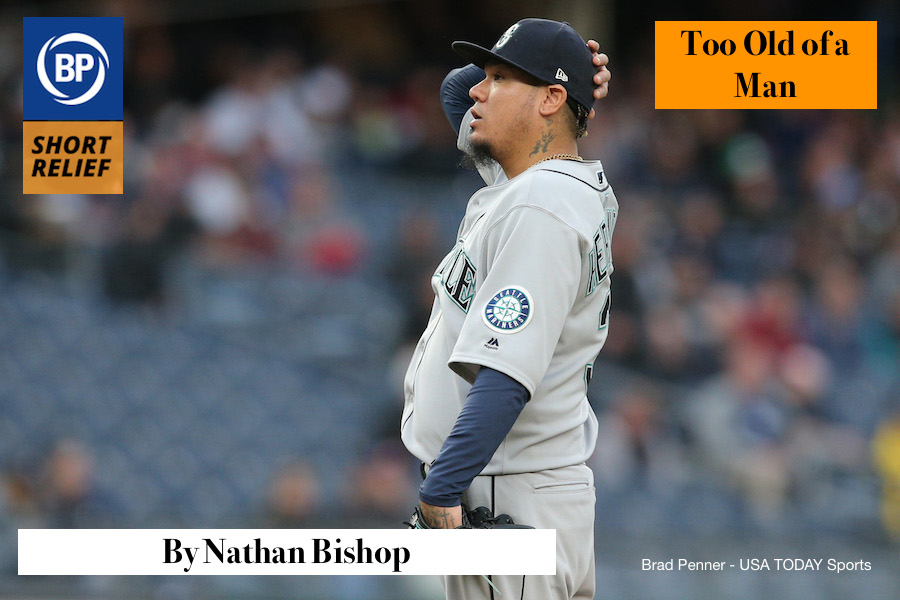

Funko Field at Everett Memorial Stadium, home of the Everett Aquasox, is located just shy of 30 miles from downtown Seattle. Culturally, well, let’s just say a city that runs on blue-collar labor and a nearby naval base has a different feel than the nearby metropolis trying desperately to become San Francisco 2.0. The Aquasox are the Rookie League affiliate of the Seattle Mariners. The team serves as the landing spot for recent draft picks, or international players getting their first taste of baseball in America. Today they are also the home of the most important Seattle Mariner of the past decade, and the greatest pitcher in franchise history, Félix Hernández.

Everywhere, there is youth. The birthdays of current Aquasox compress tightly around the late 90’s and early 00’s; a collection of babies born into a world of Star Wars prequels and the first time the Backstreet Boys were cool. The team’s manager, Louis Boyd, is 25. Yet, on the mound stands Hernández, still somehow only 33, but his skin is worn, and he somehow appears both slightly plump, and achingly gaunt. In a place built for the future, he is the past. Yet, he is here.

I wanna grow old

Without the pain

Give my body back to the earth and not complain

Félix never truly experienced the minor leagues as a prospect. He was signed at 16, destroying this very same Northwest League at 17, and within two years he was in Seattle, throwing eight shutout innings against the Twins before his 20th birthday. A talent like Félix, one so good and so young, recalibrates expectations. When a player has the stuff of vintage Pedro Martínez and the ability to deploy it in the major leagues all before legal drinking age, fantasies compound on fantasies. Why stop at winning a Cy Young Award? Why not win four, five, or more? Why set team records when you can set all-time records? Why just the Hall of Fame, and not The Best Ever?

Paradoxically, for a franchise utterly devoid of meaningful accomplishment, Félix isn’t even the first player in Mariner history to inspire such dreams. For a previous generation, it was only a matter of time before Ken Griffey Jr. broke Hank Aaron’s home run record, confirming what felt like his destiny of being the greatest player of all-time.

Junior’s twenties were at least wedded to playoff appearances, and national advertising campaigns. He’ll always be remembered. Félix toiled, every fifth day, year after year after year, for a lost franchise broken beyond repair. He also committed the one great sin that Griffey never did: He declined before he left.

I wanna have friends

That I can trust

That love me for the man I’ve become, not the man that I was

The top of the second is over in Everett, and Félix Hernández is walking off the mound. His body has been breaking for years, but recently it seems his spirit has finally joined it. He was the hope of an age, the prospect even the Seattle Mariners could not break. He won a Cy Young, and threw the last perfect game in Major League Baseball. Start after start, for the better part of a decade, he was the face, body, and soul of a franchise that had practically nothing else to offer. He was greater than we expected, for longer than we deserved, and then, in a blink, it all ended. Félix has been falling for years, and now here he sits, his past falling into the team’s rising future, soon to dip below the surface.

Félix is walking off the mound, his day complete. He threw two shutout innings, and that’s enough. All we want is one more start. One more chance to remember, and to say thank you. He was all we had for so long. For some of us, he still is.

When I was 13, Tim Wackman called me “MasterBates” in math class.

It was deeply embarrassing, of course, because everything that happens to you at 13 is deeply embarrassing, until my math teacher pointed out that someone named “Wackman” didn’t really have a leg to stand on when it came to embarrassing surnames. It was the early ’90s and math teachers were still able to say things like that and throw erasers at us without getting into trouble.

Eventually, most of the world grew up, and in addition to coming to frown on math teachers’ eccentricities, decided turning my last name into a punchline wasn’t that important. And for those who didn’t grow up, I came to understand that this was more their problem than mine. I’m sorry for my son and daughter, who will have to go through the same process, but I’ve mostly made my peace with it.

Even so, I’ve gone back and thought about that day often. I’ve thought about Tim’s obliviousness to his own vulnerability and I’ve thought about why he felt making a poor joke, loudly, in the middle of math was going to up his Q-Rating at Chippewa Middle School. I didn’t understand it.

Until yesterday, when I was watching the Twins play the Royals. Ned Yost summoned Richard Lovelady from the bullpen. And suddenly it all made sense. I couldn’t not point it out, suddenly transforming me into the Wackman.

We are in a strange fraternity, Mr. Lovelady, Wackman, and me. It’s a fraternity with Jack Glasscock, Rusty Kuntz, Johnny Dickshot, and Dick Pole. We don’t get to pick the names we’re born with, but we have the power to change it. Instead, we’ve all chosen to live in glass houses. And since it’s perhaps the lowest form of humor, the least we can do is shatter our own as we chuck rocks at each other’s. Because it’s apparently impossible to hold fire, and none of our parents will acknowledge what jerks they were.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now