It’s the beginning of the third week of May, and my college’s commencement is over, but I’m still working on my end-of-semester grading. The seniors’ evaluations are all done, of course—and they’ve got their diplomas in hand, as of midday Saturday—and everything else that I have to read and respond to and affix a number to will be done by the midweek deadline. That’s true because it’s always been true, because it has to be true: what must be done will get done, even if it doesn’t feel that way in the moment. There are, of course, exceptions—disaster strikes, panic sets in, priorities change—but I’m talking about the basic exhausting inevitability that looks more or less like success. The tasks are complete, obligations met, and recompense delivered, in whatever form that takes.

But everything comes with a cost, even when it goes well enough. For my students, as the term ends, that usually means too little sleep, some kind of illness setting in, stomachs sour from coffee and stress and uncertainty about the future, the friction between confidence in knowledge and risk in innovation pricking at assignments’ edges. It’s familiar territory—I swam through nine years of it—and though the grading pile doesn’t bring with it the same kind of stress the student side brought, the frantic feeling is replaced with weight, with repetition: more than two hundred writing assignments have become my responsibility since April 30. It’s the reps that get to me now, and I don’t mean just the volume of pages.

I’ve spent the last two weeks wearing wrist braces while I do the endless typing of comments. I got them when I was working on my dissertation, and they really do help to curb the soreness. I don’t have carpal tunnel; I’d like to avoid it; I like to think these help that, too. But they make people pull up short when they walk into my office. They ask what happened and I sheepishly get to say nothing, by which I mean nothing unusual, nothing but what I expect, nothing but what comes with the territory. I didn’t dive for a ball, I didn’t fall while skateboarding, and I certainly didn’t shove anyone out of the way of an oncoming car. I’m just typing.

In Steve Rushin’s 2013 book, The 34-Ton Bat, a celebration of the objects of baseball, he discusses the development of that now-ubiquitous piece of equipment: the fielder’s mitt. Within that discussion, he tells the story of Lou Gehrig, who embraced the glove and whose desire to take advantage of its construction—to actively try to catch balls in the webbing and not in the palm or square on the fingers—certainly contributed to his longevity. Even despite that, “X-rays taken in 1938 revealed seventeen fractures in Gehrig’s hands, at least one on every finger, injuries through which he famously played for 2,130 consecutive games.” It was nothing, nothing except what it took.

I’m just back from visiting northern Michigan this weekend, where I represented my family on behalf of my great-grandfather, Joe Linder, on his induction into the Upper Peninsula Sports Hall of Fame. My great-grandfather, it turns out, was a pioneering hockey player at the dawn of the 20th century, playing on the first professional hockey team and helping to import and popularize the game in Michigan and in northern Minnesota. For his contributions, he also was inducted into the US Hockey Hall of Fame in 1975.

Until this weekend, all of my information regarding great-grandfather came to me through second- and third-hand stories from his sons, now both deceased as well. But this weekend I met a researcher, John Haeussler, who has become deeply familiar with Joe and his accomplishments, and from whom I learned that even Joe’s birthdate is in question thanks to unreliable record-keeping, fires, and my great-great-grandfather likely knocking up my great-great-grandmother out of wedlock in late 1883, which required a shotgun marriage and extended honeymoon several counties from their home until after Joe’s birth in 1884.

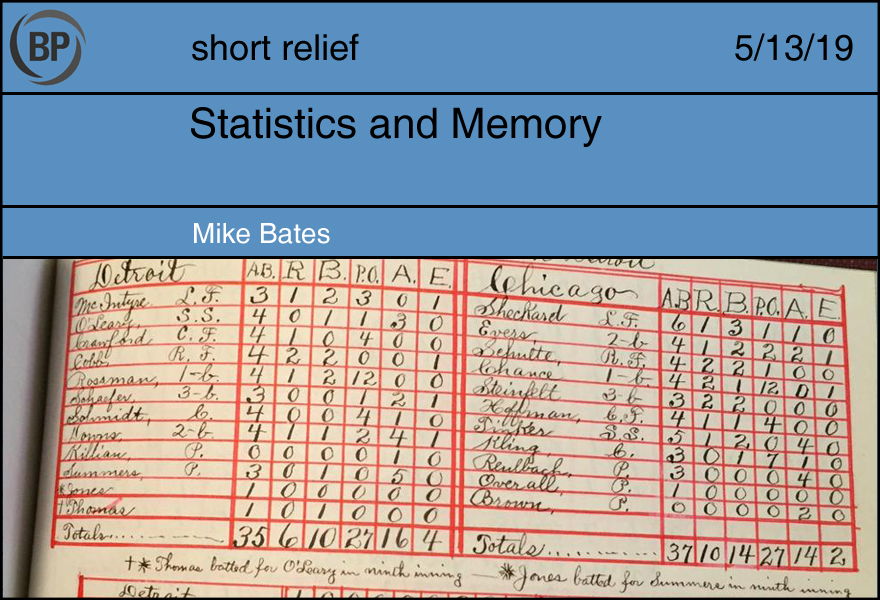

I don’t even really know how good Joe was. All we have are a few deeply biased newspaper accounts from the turn of the century and the faulty memories of old men who vouched for him. We don’t have anything remotely close to a statistical record. We think he was great, for his time at least, but we simply can’t peel back the hazy curtains enough to know. It’s wonderful to have him be recognized for his accomplishments, but it’s fairly maddening not to know what most of those accomplishments were. I mean, my grandfather claimed his dad “invented the pure body check,” but who knows if and how and how often that was ever implemented in his games?

I bring up all of this so that I can say how grateful I am for baseball’s statistical record, which reaches back to long before my great-grandfather was (probably) born. There is still so much we don’t know about baseball in the 19th century. But we know who Jim Creighton was and we know much of what he did! We know that Cap Anson was a hell of a player and a hell of a bastard! We can see not just the photos of Three-Finger Brown’s famous hand, but what it allowed him to do to hitters! The picture is so much more complete for all of these players thanks to the robustness of the statistical record.

The depth of that record, unique among the major sports, allows us to see across generations, even if so much has changed. It allows you to remain connected to our shared history in a way that I’ll never be able to connect to my personal one. My past is out of focus, and it likely always will be.

A few days ago I woke up actually laughing to myself. I looked around the room to make sure I was where I was supposed to be. I had dreamed that I was in some location unknown to me with baseball friends Sarah, Mary, and Jen. In the dream, we were all staying in a rental home and I honestly have no idea why we were all together, but I’m guessing it was for some roadtrip baseball game shenanigans.

We were all moving about the house, doing our separate evening routines as it started to get dark. The plan for the evening was to unpack, cook dinner together, and then lounge until time for bed. There was music playing and light laughter coming from the kitchen as Sarah and I sat in the living room. All of a sudden, there was a loud noise and the wall looked like someone was trying to break through from… inside the wall? Instead of staring and waiting to see what was going to happen, Sarah and I began to yell for Mary and Jen to get the hell out of the house immediately.

Whatever or whoever was coming through the wall wasn’t moving with extreme haste, and yet it felt like everything was happening in the blink of an eye. Suddenly, Mary and Jen rush into the room, Mary wielding a baseball bat. They ran straight toward the ghost or monster coming through the wall and started trying to beat it into submission. With a deep, guttural sound Mary swung the bat with the power of Jim Thome.

That’s when I woke up. What a hilariously bizarre dream. Or was it a nightmare with terrible writing?

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now