Lou Castro, as he preferred to be called, made his major league debut on April 23, 1902 for the Philadelphia Athletics. His professional baseball career lasted a paltry 42 games, in which he hit .245 with 15 RBI. On their way to winning the pennant, the Athletics removed him from the team in favor of Danny Murphy, who hit .313 and was a superior fielder. Any other player would have become a footnote in history; instead, Lou Castro became one of baseball’s biggest mysteries.

In 1913, while acting as a player-coach for Portsmouth, he gave an interview in which he claimed that exiled Venezuelan president, Cipriano Castro, had attempted to come to the United States to see him, as he was Castro’s nephew. Further, Lou asserted that he had moved from Colombia to New York at the age of 8 in order to escape his wealthy family’s ties to the outburst of revolutions. These remarks, which Lou would contradict at various points in his life, marked the first breadcrumbs of a trail that equally delighted and frustrated journalists for over a century.

Following this interview, baseball writers across the country began to theorize about the origins of the first Latinx player in American professional baseball. Some asserted that Cipriano Castro was actually his father, and Castro had undergone a series of name changes––from Luis Miguel to Louis Michael to, simply, Lou––in order to hide from the elder Castro. Others took a less serious approach, thrusting upon Castro the title of “The President of Venezuela.”

Known as a clown, Castro took much of this in stride while privately attempting to distance himself from his heritage. In 1917, he applied for naturalization, citing his birthplace as Medellin, Colombia. From this point on, he insisted his birthplace was New York City. He was born and raised in New York on the 1930 census. He was a lifelong American when he joined the Association of Professional Ball Players of America in 1937, broke and approaching death. He was a birthright citizen when his body was buried four years later in an unmarked grave in Queens.

In life as in death, Lou Castro teetered between remarkable prestige and complete irrelevance. He was either the close relative of a wealthy Venezuelan president or he was an American struggling to make a career in baseball. The more he was pulled to the former, the more he clung to his ability to pass as that white ballplayer.

For over 60 years, Lou got his wish; he was recognized as a native New Yorker. Yet, historians kept chipping away at Lou’s story until they revealed who Lou Castro really was: a native Colombian who immigrated to America as an eight-year-old. Not buried in ship records or newspaper interviews are the reasons why Castro so desperately pretended otherwise. But then, maybe the answer is right in front of us.

Whenceforth I received the news that the great Bone Head from Mud City was applying saliva to the ball before releasing it to the batter, I was right steamed. Myself, returning straight from a season that saw me ace thirty-one victories for my club, well yes-sir, I feign ignorance as to why a gentleman pitching for a club coming off a sixty-eight-win year might think he himself would be the right solid chap to fix what is otherwise a boondoggle of a task. Ed Walsh…that tippler? Onethinks he should return to the mines and leave this great game for those of us who can sleep well each eve’.

Listenup pal, I ain’t breakin no rules and another thing is ya never seen me do it, ya hear? I apologize to the gentleman from Pennsylvania, I truly do. It must trouble him greatly to be only one face on a winning team that will be forgotten by history as one simple chump in the crowd. I play for the books, and if I could tell ya anything bud I’d tell ya not to take any wooden nickels, unless you really think you’re the next Rube Waddell…well, perhaps in constitution only…

My good sir, let me first reach out to you in gentlemanly spirit to commend you on your accomplishments as a member of Chicago’s true working-class base ball club. I did not mean to diminish your abilities in the aggregate, rather, to illustrate the manner by which our great game only selectively decides to enforce the rules by which we are all–per the word of the boss–meant to follow. Nevertheless, I have it on good authority that you, Mr. Edward Augustine Walsh, indeed throw a spitball, which not only confuses batters but gives you a competitive advantage which both buttresses your good standing on your local club and tosses a bone to those degenerate bookies who seek to defame our great game by pulling it into the dim-lit alleys filled with liquor and sin. At this stage, I only ask you to recognize what my ability might be were I to apply my own saliva to my pitches–perhaps I, too, could reach the forty-win-mark you so “purely” achieved through your own volition.

I dare you losers to bean me. Dare you.

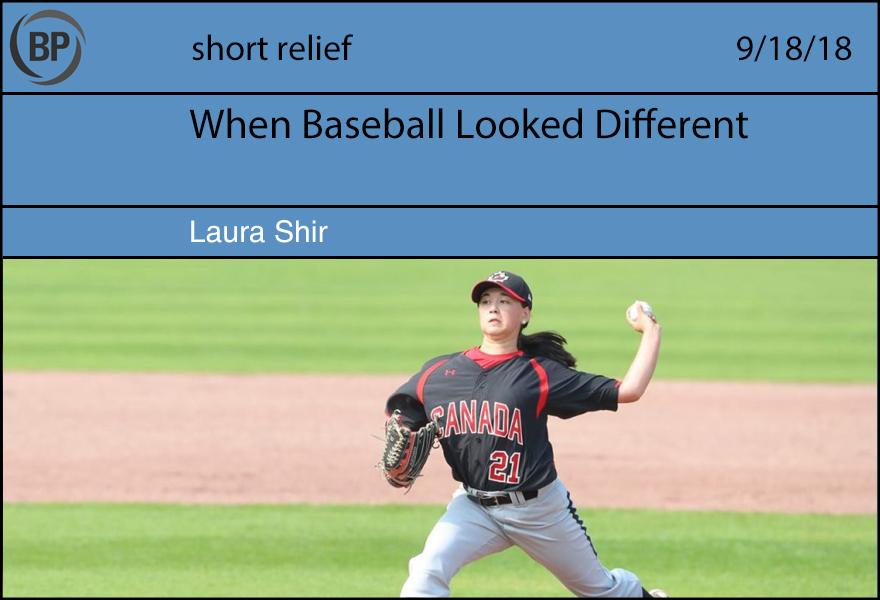

It was a letdown, when this year’s Women’s Baseball World Cup ended, to go back to watching men’s.

Much has been written about the hard baseball details of the women’s tournament: the match-ups, the spin rates, the turf, the rain, the sharpness of the double plays and the joy of the home runs. The athletes deserve to have these details covered by the national sports media; they deserve attention and accolades, sponsorships and scholarships. But what made an unexpected impression on me… was what the players looked like.

Appearance is a fraught topic for female athletes. Too often, women in all professions, but particularly those in which their bodies are the focus of their work, are reduced solely to their beauty rather than their ability. The egalitarian approach would be to ignore appearance, lest we distract from the real point: skills, mastery, the opportunities that generations of female athletes have fought so hard to access. But in this case, the way the athletes looked added to the emotional impact the tournament had on me.

They looked like women, of course. But what does that mean? As a queer woman, what that means to me changes every day. I’m cisgender, which means when I was born, a doctor looked at me and said “it’s a girl,” and 24 years later I still think that doctor was right. I am a woman. But the way I wear my gender, and the way my gender wears me, is a process I struggle with.

The women ballplayers I had seen before had never particularly spoken to that side of me. From its inception during World War II, the All-American Girls’ Professional Baseball League enforced strict femininity. The league forced the players to play in dresses and take etiquette classes to weed out “masculine” women, particularly lesbians. (And, of course, it was only for white women—a fact often glossed over when the league is memorialized today.) When I first watched women’s college softball, I was amused to see the colorful hair ribbons worn by so many of the players. But then I learned how even those brightly-colored bits of fabric have been weaponized. Certain straight women softball players, tired of homophobic stereotypes and more than a little bit homophobic themselves, use the bows as symbols to demonstrate that they’re still feminine, they’re not like that. Not like me.

So imagine my surprise when I turned on the Women’s Baseball World Cup, and right there on Team USA was every way I had ever considered being a woman. On Kelsie Whitmore (RHP/OF), I saw the hair I dreamed of having in high school, waist-length and mermaid-like, floating loose as she coiled her wiry strength to let a pitch fly. Malaika Underwood (1B), compact and serious, embodied the androgyny I wished for sometimes in college, as I tried and failed to be taken seriously in the queer communities there. Brittany Gomez (OF) was wearing the kind of flawless eye makeup I’ve never mastered, visible in the close-ups during her at bats. And Megan Baltzell—well, she became the only DH I’ll ever believe in, and her raw physical power made me feel like I could conquer the world.

I don’t know how any of these women define their genders or their sexualities. The way they made me feel may have no bearing on how they feel about themselves. But they gave me a gift, whether they know it or not. They taught me something I’ll never forget: There are a million ways to be a woman. There are a million ways to be a ballplayer. There are infinite ways to be both.

It was a bright, cold day in April, and the clocks were striking 7:10. John, his windswept beard a pendant commemorating his participation in a Boston music scene long since dead, sprinted across the Common, dodging carts hawking pretzels and funnel cake and holographic souvenirs depicting historic landmarks. Pursuing him were three men dressed in all black, save for the navy cap on each one’s head emblazoned with a red “B.” John widened the gap between himself and his pursuers, pushing through a crowd of tourists and ducking into the Arlington Street subway.

Exhaling for just a moment, John sunk into a seat on a train bound west. He needed to get out of the city as quickly as possible, hadn’t even had time to grab his possessions from the studio apartment he rented in the dilapidated Seaport. For years, John had resisted the increasing intensity of the Boston-New York rivalry; he was disgusted with the long commercial breaks, the interminable games, the innumerable pitching changes.

Across from his seat on the half-empty train was an enormous poster depicting a face at least a meter wide: the same navy cap atop the head, a pair of reflective sunglasses and a large smile completing the terrible visage.

John averted his eyes.

The text below the head read “PAPI,” and John did his best to expel that word from his mind as he began to take stock of his fellow passengers. Although only a dozen or so others littered the train car, every person wore the same near-black blue, littered with that red logo. John began to feel his heartbeat in his hears, his palms growing damp as he waited for the train to reach the city outskirts, where he would catch another train bound further west.

He knew he wouldn’t reach that train, however, because as the other passengers exited at Kenmore, they revealed a man dressed in neck-to-toe black, topped with the cruel navy cap, seated at the far end of the train. John froze. The man stood, approached John with a purposeful stride, and sat beside him.

***

When John woke, he was in a large, green room, fluorescently lit, seated across from the three men who had chased him through the park. Shaking off the grog, John noticed he had a gash on his forehead. The wound pulsed with pain as the three agents questioned him.

“We’re agents of the Ministry of East Coast Bias.”

John curled his lips.

“Do you know this man?” One of the agents held up a photograph of a thick-necked figure, and John exhaled deeply through his nostrils. “Do you know Mike Trout? We know you have connections with his cell of rebels. We know you have been fighting with him and others for years against REDSOC. We found these when we searched your apartment.” One of the agents tossed a smattering of files on the table.

“Shorter commercial breaks. Limiting mound visits. Relocating REDSOC. These are radical plans. You’ll begin your re-education sessions tomorrow.”

***

Three weeks later, John sat in a slightly-too-small faux-wooden seat at the 200-year-old ballpark. He watched REDSOC do battle with New York. They had always been at war with the Yankees. John let the crowd’s cheers and sighs wash over him, as Clone Pedro Martinez squared off against recently signed New York starter Bartolo Colón.

He loved Big Papi.

(Photo courtesy Dylan Zobel.)

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now