The thing about getting old isn’t that it makes you smarter; “smart” and “wise” are too often conflated. I am definitely not as smart as I once was, in my early twenties, when I was sleeping a positive number of hours per night, regenerating brain tissue, reading the dictionary for new words to learn. I only remember one now, cicatrix—a good word, but I can never think of a place to put it. No, old age robs you of everything in equal measure; what it exchanges is simply a larger sample, more ground with which to form perspective.

Many words have been devoted to the latest contortion of baseball strategy, culminating in an All-Star game that looked all too similar to its Home Run Derby cousin. There’s no need to rehash the rise of the Three True Outcomes, the dwindling of balls in play, the death of the stolen base; these appear to be vestigial organs of baseball’s headstrong youth, like the popularity of gambits in chess or the romance of going off to war. But as Rob Mains has catalogued in his weekly series about the 1968 season, 50 years ago we appeared to be staring at a similar precipice, only to pull ourselves back. A snap of the fingers, a sharpie to a few lines in the rulebook, and everything could be fine again, hurtling toward some new disaster on a different horizon.

Some of the wistfulness of the fields behind us is, to me, misplaced. We mourn the excitement of the defense in action, the triples into the corner, and the nauseated thrill of the contact play, but of course those are only the gold standards of batted balls. Not an insubstantial amount of our sport’s history has been devoted to watching thin men with thick facial hair roll over soft grounders to shortstop. Statcast has given us xwOBA, and conjured up a value for a hitter based on how they hit; we need them to go one step further and extend the concept to their entertainment value. Every fly ball is a sweet, momentary promise, especially to the gullible crowd, even though they are nearly all a lie. The ground ball leaves the center field camera’s view and the viewer is forced to think, “eh, maybe that’ll find the hole.”

So as the stick-less shortstops of past generations have been replaced by shorter, quicker versions of our outfielders, it’s not quite the loss that we tend to see it as these days. But there is a loss. Because there is a certain type of ballplayer that may have already disappeared.

If someone were to ask you if you wanted a player to have a higher on-base percentage than slugging percentage, the answer would probably be “no.” Even though OBP is slightly more valuable than SLG, in terms of run creation, the numbers aren’t really scaled properly; there’s only so high OBP can go, unless you’re Barry Bonds, and it’s much easier to eclipse that mark when you can reach 4.000 in slugging percentage with a single at-bat. This is why we couldn’t just stick with OPS, after we figured that out, and had to move to bigger and better metrics.

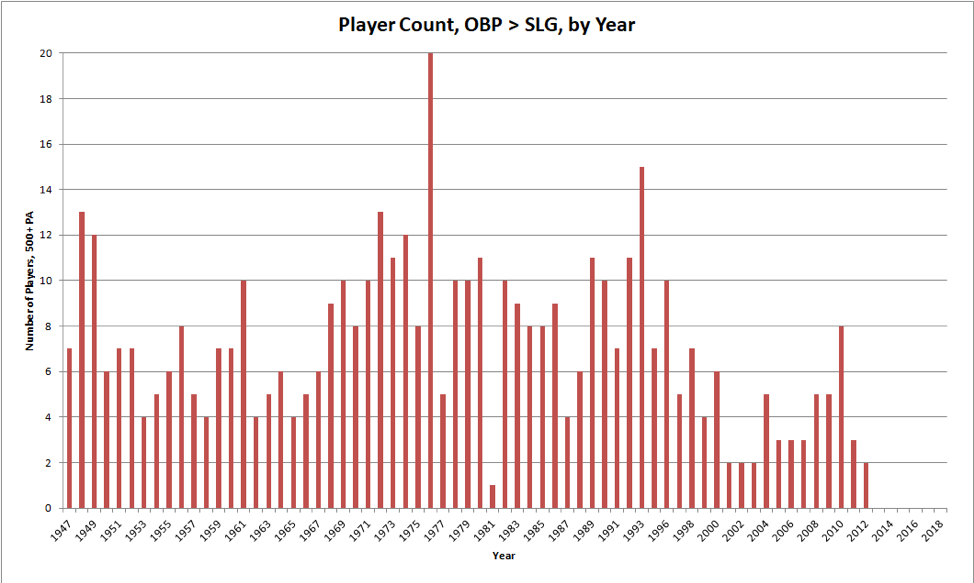

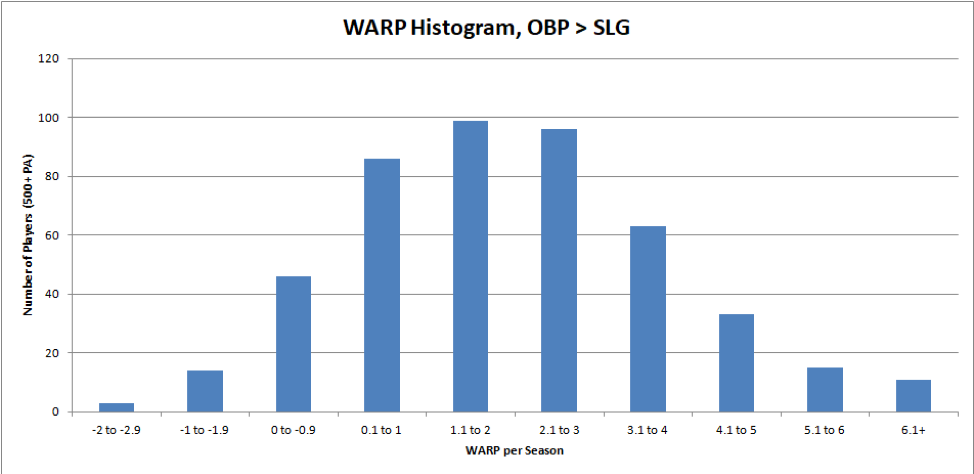

So when you visualize a player who fits this category, it’s probably one of those 5-foot-4 utility infielders who could only get on base when they forgot to swing. And sometimes, that’s true. There have been 466 seasons that qualify in the integration era of baseball, averaging about half a dozen per year. It’s a fascinating list. Eddie Yost, the archetypal one-tool hitter, managed the feat seven times, only one of them a below-average offensive season. Alfredo Griffin and Horace Clark, two decades apart, posted identical .258/.254 lines, and both were above replacement level thanks to their defense. Adam Dunn’s on there, right next to Chris Getz. That’s how you know you’re getting some quality data.

The Yost Line might seem at first like a dubious achievement, but some great players regularly achieved the mark. Richie Ashburn, in the friendly offensive environments of the 1950s, Ozzie Smith did it nine times, to no great surprise; Rickey Henderson seven, including seasons 20 years apart from each other (.420/.399 in 1980, .368/.305 in 2000). In 1980 alone, Henderson (9.6 WARP), Willie Randolph (6.4 WARP), and Dwayne Murphy (5.4 WARP) all put in fantastic seasons while reinforcing the stereotypes of the leadoff hitter with a higher OBP than SLG.

As you’ve probably noticed from the graph above, those days are over now. The decline began in the mid-90s, while some other era of baseball got underway, and never recovered. The last two players to qualify for the batting title and post a Yost Line are Jamey Carroll (.343/.317) and Jemile Weeks (.305/.304) in 2012. Since then, every attempt has fallen short on plate appearances: Ichiro Suzuki, A.J. Ellis, Eric Sogard. Michael Bourn came closest in 2015 with a .310/.282 line in 482 tries. But clearly, these types of players have been squeezed out of starting jobs by slugging teammates and efficient general managers.

This year, 30 hitters are above the Yost Line heading into the second half, led by our old friend Eric Sogard and his .076 split (.241/.165). It’s unlikely he’ll be allowed to build on his record, however. In fact, only one player is on pace to break the vaunted 500-plate appearance mark, thanks to his exemplary defense and terrible team: Delino DeShields Jr., he of the .208/.301/.275 line. He’s not about to join the echelon of the greats, but at a one-win pace, he’s no Rougned Odor. These aren’t bad players, just largely flawed ones.

The question is whether DeShields’ strange little run at history, or any of this, matters. And the answer is no, if the subject is winning. The stereotype of the gritty, pesky second baseman with the Two-Face snarl and the bat choked halfway up has faded because, for the most part, teams have figured out better ways to allocate his at-bats. In the modern game, there is so much talent that nearly everyone can do everything.

Aesthetically speaking, I do feel like we’ve lost something, the way we do when some strange and minor species goes extinct. There are really two ways you can appreciate a sport: the sheer athleticism and prowess of its players, and the way they work around the constraints placed upon them by the rules and their opponents. There are plenty of fans of the former, and for them, these are obviously harvest days; men hit and throw and run to degrees unmatched in history.

As enjoyable as hustle is, the viewing experience of the average Logan Forsythe or Travis Jankowski at-bat just doesn’t resonate with the heartstrings on quite the same level. But from a strategic standpoint, it’s far more interesting for baseball to have different types of players who employ different skills and techniques to reach success. Just as it would be boring if one type of football offense were undeniably superior to all others, or if one chess opening gave White a guaranteed advantage, dominant strategies ruin games and sports alike. Mike Trout is the best player in baseball, but we don’t need every team to field the nine closest approximations to Trout they can assemble. We’re better off with Delino DeShields, and even a few Eric Sogards, getting things done the only way they can.

The good news is that while DeShields may be the last of his kind, in baseball, there’s no such thing as extinction. Fifty years from now, we could be talking about 2018 as the end of the bandbox era, the arrival of the 400-foot foul pole, and the resurrection of speed and defense. It could happen in the blink of an eye. When you get old enough, everything seems to.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now