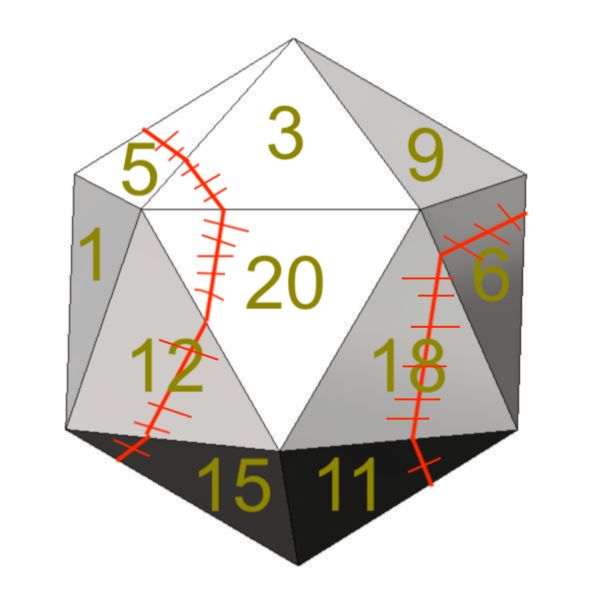

After a 10-year study, countless hours of research and several per diem meals reimbursed, scientists and analysts in professional baseball in conjunction with the Tabletop Gaming Association of America have reached the following conclusion about the changing shape of the baseball over the past few decades. The baseball as we know it, gradually changed from its classic “sphere” shape to a icosahedron.

There were several whispers throughout the league of the baseball’s shape and its impact on specific outcomes. To address these rumors, several tests were performed involving current and former major league players. Interviews were conducted with the manufacturer of the equipment. They also examined the baseball:

[Figure 1]

On top of that, hours of real game data was analyzed. What they found was remarkable depending on how the face of the baseball landed, virtually 100 percent of the time these were the outcomes:

1 – STRIKEOUT

2 – STRIKEOUT

3 – GROUNDOUT (MEDIUM)

4 – SINGLE

5 – DOUBLE

6 – STRIKEOUT

7 – POPOUT

8 – HOME RUN

9 – GROUNDOUT (HARD)

10 – SINGLE

11 – FLYOUT (SHORT)

12 – FLYOUT (MEDIUM)

13 – FLYOUT (DEEP)

14 – WALK

15 – LINEOUT

16 – GROUNDOUT (SOFT)

17 – STRIKEOUT

18 – HBP

19 – TRIPLE

20 – WALK

What this means for the future of baseball remains to be seen, however it would explain why several math-inclined introverts have accepted front office positions in baseball.

This Wednesday the 23rd was the 156th anniversary of William Ellsworth Hoy’s birth. Hoy is widely recognized as the best Deaf baseball player in MLB history.

Born in Ohio in 1862, Hoy lost his hearing via meningitis at age 3. Bright and motivated, he enrolled at the Ohio School for the Deaf at age 10 and graduated at 16 as the valedictorian. In the 19th century, most deaf people were trained vocationally, and Hoy learned shoe repair and had his own shop within a few years. He played neighborhood baseball on the weekends or the slow summer season, and was spotted by a scout, Natural-style, who invited him to join the Kenton, Ohio team. From there, he left home and joined the Northwest League.

Hoy, thin and 5’6” at best, had little power behind his bat. Worse, he was distracted at the plate, where he struggled to discern whether the umpire had called a ball or strike. Legend has it that Hoy requested of his Northwest League manager that the third base coach signal balls and strikes so he could follow along. The manager obliged, and Hoy hit over .300 the next two seasons. It’s still debated whether Hoy’s request was the impetus for the signals umpires used today.

“Dummy” (ugh) Hoy made his major league debut in 1888 and played for seven teams across his 14 years. His best seasons were with the Reds, 1894-97 and 1902, where he slashed an average .293/.392/.402 with 176 stolen bases (he’d steal 594 across his career). As the steals suggest, Hoy was fast and played centerfield shallow, which, combined with his good arm, meant he racked up putouts and assists, once throwing three runners out at home plate in a single game. Since he couldn’t hear calls from the other fielders, they deferred to him—he’d yell out if he had it and say nothing if he didn’t. Tommy Leach, Hoy’s roommate and fellow outfielder in Louisville, said many of his teammates also learned basic sign to communicate with Hoy.

But perhaps the most intriguing part of Hoy’s story is that, at the time of his debut, he wasn’t the only Deaf player in the Major leagues—there were two others playing at the time, and several more on the books. Hoy even went up against Deaf Giants pitcher Luther Haden Taylor, the only such matchup in MLB history, in 1902. Hoy and Taylor are said to have chatted briefly in sign before retaking their positions.

People often think progress means life is automatically better for d/Deaf and disabled people. And in some sense, it’s true—I mean no one’s walking around calling me “Dummy.” But with progress, especially in technological developments, comes a change in cultural attitudes—if the deaf person can be “fixed” it follows that they should be, and it’s no longer the majority’s responsibility to make an effort to communicate in a way that’s mutually accessible. It’s difficult to imagine my coworkers changing their everyday habits to make things easier for me, or taking time out to learn ASL. Our education system glorifies “mainstreaming” as integration, but in reality, the goals set for deaf children are more about blending in, endlessly practicing to speak and listen when that energy might be put toward other skills.

I think often of the talented people that are lost this way. It doesn’t seem a coincidence that we haven’t seen a culturally Deaf, ASL-using player on the major league field since Hoy, age 99, threw out the first pitch at Game 6 of the 1961 World Series.

I hope I’m wrong, and that the next great Deaf player is just around the corner, ready to be a role model for those kids seeking validation in their own language, culture, existence. Until then, I’ll keep rooting for Hoy—Cooperstown or bust.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

Fixed your typos for you.

Shouldn't Curtis Pride count, or is there something about this I am not understanding?