From the NLCS MVP as a rookie in 2013 to extended stints on the disabled list in both 2014 and 2016, Michael Wacha has been dealt a wide range of hands during his first five seasons as a big leaguer. With significant question marks surrounding the 2018 starting rotation, the Cardinals are expecting a strong performance from Wacha this year. Fortunately, repertoire developments and new data suggest that the 26-year-old Wacha is primed to take the next step in his career.

Here’s a breakdown of Wacha’s pitch usage last season, via Brooks Baseball:

| Pitch Type | Frequency | Velocity (MPH) | pfx HMov (in.) | pfx VMov (in.) |

| Four-Seamer | 52.8% | 95.6 | -3.77 | 10.41 |

| Changeup | 18.2% | 88.3 | -5.35 | 6.63 |

| Curveball | 11.4% | 77.1 | 4.03 | -7.57 |

| Cutter | 17.6% | 91.3 | 1.09 | 6.29 |

When Wacha arrived in 2013–less than 12 months after being drafted 19th overall out of Texas A&M–he was advertised as being a tall, fastball (64.2 percent)-changeup (26.7 percent) pitcher. While the fastball and changeup still make up the majority (71 percent in 2017) of his repertoire, his tool bag is substantially deeper now than during his debut season. His cutter–after being deemed potentially “scrap-worthy” in previous seasons–improved in 2017, and his curveball became an out pitch for the 26-year-old, subsequently playing a role in “completing his repertoire.”

But what’s most interesting about Wacha is his innate ability to pitch tunnel (and his tunneling improvements, really), two findings uncovered using BP’s new pitch tunneling updates. As detailed by Jeff Long, Harry Pavlidis, and Martin Alonso, Pre-Tunnel Maximum Distance (aka PreMax) is the “distance between back-to-back pitches at the decision-making point.” In other words, this is the perceived distance difference between two pitches when it’s time for the batter to make a decision. Essentially, a smaller PreMax value is better, as it represents a “properly-tunneled” pitch pair. For reference—pitch tunnel data can be found in BP’s stats section—according to Long, Pavlidis, and Alonso, the average PreMax across all pitch pairs was 1.54 inches.

Considering that fastball-changeup remains a primary sequence for Wacha, and the fact that both pitches carry a similar movement profile, his ability to tunnel the two becomes supremely important for his long-term success. In his debut season, Wacha’s changeup was particularly effective, yielding a .171 batting average and .205 slugging percentage. In the four seasons since 2013, batters have experienced slightly more success against the pitch, batting .219 with a .354 SLG. Yet, even with these better results put forth by opposing hitters, a .219 AVG and .354 SLG is still very good, from a pitcher’s point of view.

Admittedly, “ability to tunnel” is an inherently vague term, particularly for those not yet familiar with the recent updates here at BP. But as stated above, PreMax is currently the best way to quantify a pitcher’s “ability to tunnel,” as it represents what the batter sees at the time to decide whether or not to swing. Remember, the smaller PreMax the better, and considering a baseball’s rough diameter of three inches, we are seeing values that may or may not be easily distinguishable to the hitter.

Here is Wacha’s average fastball-changeup PreMax, in inches:

| 2017 | 1.40 |

| 2016 | 1.55 |

| 2015 | 1.45 |

| 2014 | 1.43 |

| 2013 | 1.45 |

Excluding a small blip in 2016–he did spend time on the disabled list that season–Wacha has yielded encouraging PreMax averages with the fastball-changeup sequence. Using the qualifier of 50 pitch pairs, the 2017 league-average PreMax on the fastball-changeup sequence was 1.50 inches. I chose to include a 50-pitch pair qualifier, because if a pitcher is throwing the fastball-changeup sequence 50-plus times he must be fairly confident in its ability to retire hitters. Wacha was one-tenth of an inch better than the league-average at tunneling his fastball-changeup sequence.

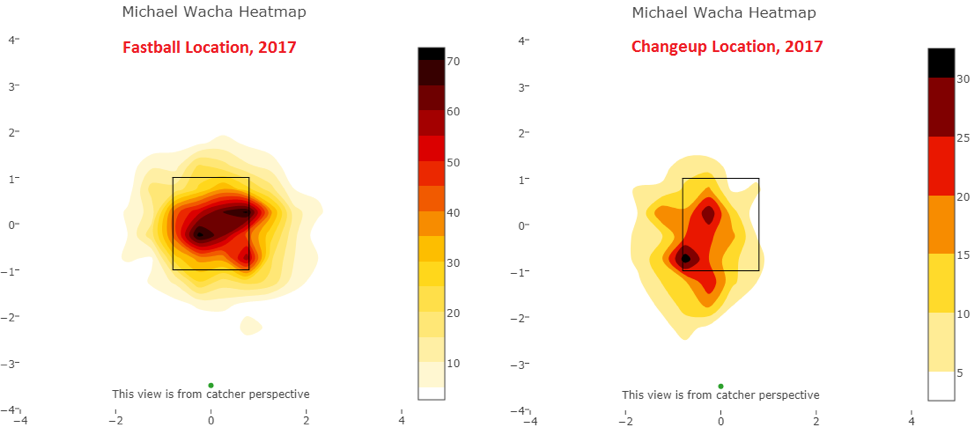

When recognizing the fact that his changeup (-5.35 inches) possesses more arm-side horizontal movement than his fastball (-3.77 inches), Wacha’s 2017 heat maps are a perfect representation of a pitcher focused on pitch tunneling. As you will see below, both of Wacha’s changeup core locations are shifted one deviation leftward (from the catcher’s/batter’s point of view) from the fastball core locations, consistent with passing through the same tunnel point:

Numbers almost always tell the story, but for those that require visuals, we will now turn to the work of @cardinalsgifs to better understand the concept of pitch tunneling.

First, a Wacha vs. Jose Bautista matchup from April:

Using BP’s new Ineractive Matchup Tool, we’re able to get our first real glimpse of pitch tunneling through the eyes of the hitter. Here, we take it one step further by bringing the still images to life in GIF form, with the tunneling portion represented by the yellow part of the trails. And to better appreciate the effectiveness of this sequence, let’s see exactly how Bautista reacted to the two pitches:

And finally, for the stereoscopic learners:

While fastball-changeup is the primary sequence order chosen by Wacha, he does still utilize the changeup-fastball sequence, as you’d expect. Using PreMax, we learn that Wacha does not tunnel this version of the sequence nearly as well, averaging 1.59 inches. But, given his propensity to bury the changeup down, followed by elevating the fastball–changing the hitter’s eye level–we can provide reason behind the disparity.

Here, we see Wacha utilize this exact sequence method versus Nick Markakis later in the season:

Using the Interactive Matchup Tool feature:

Wacha did not scrap the cutter last season. In fact, he used his cutter (17.6 percent) almost as frequently as his changeup (18.2 percent). Given their respective movement profiles, these two pitches should, in theory, still tunnel well, particularly to hitters of the opposite hand (the depth of the release point distinguishes the opposite horizontal movements longer). Sure enough, Wacha is better at tunneling the cutter to lefties (PreMax of 1.69) than righties (PreMax of 2.21).

Just ask Corey Seager about the following strikeout sequence:

To better appreciate the magnitude of difference at the plate–represented by another new pitch tunnel statistic (Plate:PreMax Ratio)–let’s experience the two-pitch sequence from Wacha’s point of view:

While not necessarily a tunnel sequence, we must also remember that the curveball has become quite a weapon for Wacha. This is a welcome development, since he badly needed to add a distinguishably different third velocity to his repertoire, as there just isn’t a big enough disparity between fastball, cutter, and changeup at times. From strictly a spin standpoint, the curveball still complements the fastball quite well, despite not possessing an ideal path for tunneling. Just ask Scott Schebler:

We are just scraping the surface on pitch tunneling data. The progress made by the Baseball Prospectus stats team over the last calendar year is astonishing. I cannot wait to find out what they have in store for us next–particularly with the Interactive Matchup Tool, as it moves toward graduation beyond beta status. Inconsistent pitchers like Wacha can benefit from delving into this data. Though the data may be a bit complex, some simple concept training should do the trick.

Credit to @cardinalsgifs for the GIFs included.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

True tunneling, the ball would disappear halfway to the plate and reappear right in front of it. Or better, behind the batter, who wonders what happened until he remembers Greg Maddux, diabolical physicist and HOF hurler, is on the mound, laughing at him.