I often enter my office building by the rear door, which opens onto a parking lot across the street from a big downtown hotel’s main entrance. A few years ago, as I crossed the parking lot, my path led near someone talking on a cellphone just a few feet from my door. The lot is a good place to make a private call if you’re staying in the hotel. Especially if you have a roommate, as I assumed this stranger did once I got closer and recognized one of the Durham Bulls, the team I covered.

The strange, deeply compromised Triple-A playoffs are the last, and most unjust, joke Major League Baseball plays on its taxi squad at the end of every Summer of No Love. The biggest and most obvious prank is a simple date: September 1 roster expansion comes along each year and guts Triple-A teams of many of their best players just before the minor-league postseason begins, leaving playoff rosters ragged and muddy, like musical tracks degraded and corrupted by too much overdubbing.

Less conspicuous are any number of deserving players who weren’t called up to the majors but perhaps still might be after (or sometimes during) the dubious Triple-A playoffs. Resentment, bitterness: yes, and fatigue too; but perhaps worse is the limbo in which those left behind find themselves. Some minor leaguers sign leases only through the end of August in order to avoid paying a full month’s rent for just a week or two of September. That leaves them homeless for a few awkward days after September 1. They may play their last few games, including championship series, out of suitcases in hotels, essentially finishing the season as visiting ballplayers at home—the fitting final estrangement of the alienation inherent in Triple-A.

Fitting, too, the alienation of having to seek out privacy in public, right in the middle of downtown. I imagined the player in the parking lot had stepped out for a homesick lament to a parent or girlfriend, or to vent frustrations on his agent, or even to interview for an offseason job. But as I got closer, I saw that he was holding the phone in one hand and a cigarette in the other. He wasn’t outside for privacy. He was outside for a smoke break. He saw me, gave a sheepish smile, trod out his smoke, and skulked away—more privacy invaded.

Shouldn’t smoke. Scarcely needs to be said, although defenses can be mounted: Durham was built on tobacco, DiMaggio smoked and many others too, and when Steve Howe (RIP) said “heaters” he meant his cigarettes, not fastballs (or his guns). But they’re terrible for us and for the environment, and they can only damage a minor leaguer’s prospects. Still, nothing seemed clearer at that moment than that he really needed that cigarette, that its dangers paled beside its brief unconflicted pleasure, and it was a shame to have deprived him.

I am trying to do dishes. I do not have a dishwasher, so the dishes must be washed by hand, a time-consuming process. I wish it were a meditative chore–the zen sand-raking of vacuuming, for instance–but it is not. It is a soppy, pruny, fiddly chore that requires just enough of my concentration to prevent thinking too deeply about interesting things, and much, far too much, of my time. Today it is taking even more time because my friend who has been traveling abroad for most of this past year has wi-fi for once and is sending me texts and snaps, dispatches from the tiny South American hill town he’s staying in. He wants an update on Seattle sports.

I do not mind taking time away from the time-consuming task of doing dishes to catch up with my friend, whom I miss very much, except I do. There is a chain of tasks waiting for me and this is eating into the time slot I set aside to complete this particular one. I just want the dumb dishes done.

People do not enjoy, in general, demands being made on their time. To spend time with someone freely is a gift, doled out second by second: I choose you, over and over. Time can also be a negotiation, whether with others (“I can talk for a minute”) or with oneself (I can leave these dishes half-done to catch up with my friend). Seizing time can also be a power play, a way to gain the upper hand in a situation:

“Your table isn’t ready just yet.”

“Submit a claim form and someone will get back to you.”

“We don’t seem to have that in stock; try back tomorrow.”

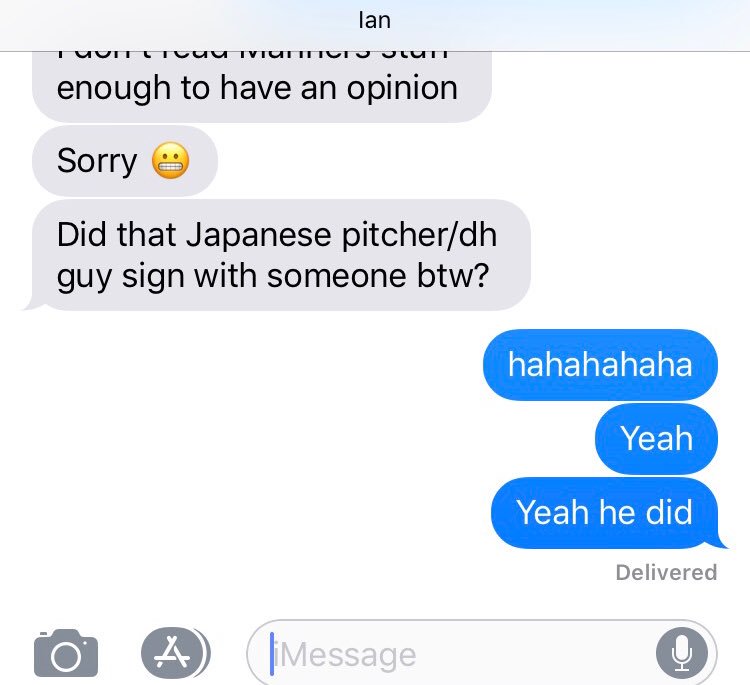

I mostly watch the Mariners, so my experiences with demonstrative time-taking, as Mr. Kyle Duerr Seager illustrates up here, are mostly Mariners-based. Robinson Cano is a time thief in the worst, most elegant way; the world will bang, whimper, end, and still, still somewhere Robinson Cano will stand astride the last bit of space-dust remaining of Earth, adjusting his batting gloves. This is a key part of seizing time: a complete disregard for the time of others, or for the constraints of time itself, to the point of utter nonchalance, a seeming inability to recognize others have time, that their time means something, too.

Just for fun, I pulled up a random Robinson Cano at-bat from September. From the time his name is announced until he steps into the box, by my count, is nine seconds. Once he’s in the box, however, he takes an additional 14 seconds before he’s actually ready for the pitch to be delivered–a few seconds of landscaping, some light gardening as he digs into the box; a few seconds to pinwheel his bat; a few seconds for the batting gloves, always with the gloves. 22 seconds. I’m sure that’s a coincidence. I time his next at-bat. Two minutes in, the count is 1-1. The next pitch hits him on the elbow. Cano, after a look towards the mound, takes his time walking down the line.

Time is a gift, and a weapon, and a privilege. Recently some women in Hollywood have wanted to make it clear that time is up for certain men; they are taking their time back. A woman is taught her time doesn’t matter as much. The time-consuming nature of household tasks is often overlooked. We give our time freely, sometimes because we want to, and sometimes because it is what is expected of us. But it does not do, to cede too easily in the negotiation of time; sometimes it’s good to remember we all have our batting gloves that need adjusting.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now