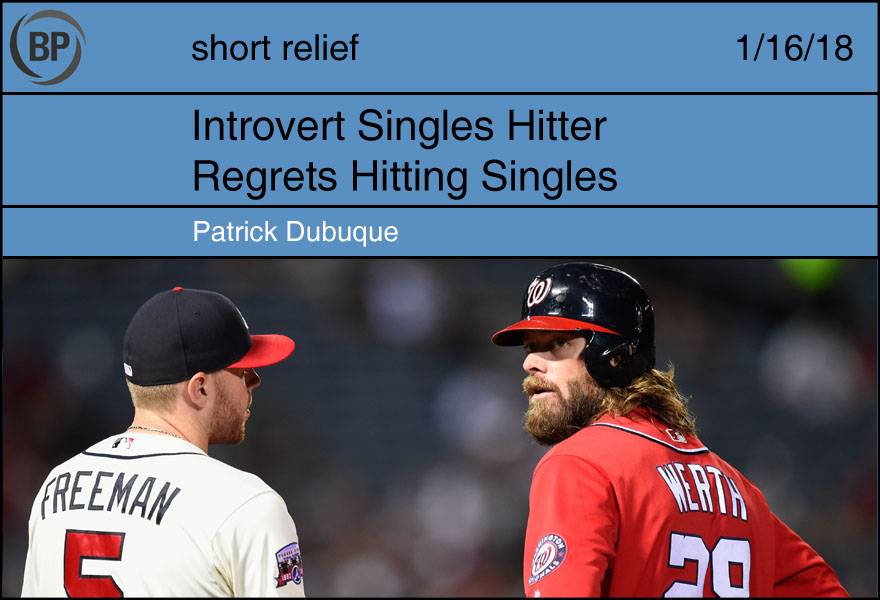

photo © Dale Zanine-USA TODAY Sports

HARTFORD, CT — Aidan Jackson, first baseman for the Hartford Yard Goats, got on base at a prodigious clip in 2017–and that’s been a problem. The 25-year-old, drafted out of Georgetown in the ninth round of the 2014 draft, was considered by experts as a token senior sign, but he opened up some eyes after bringing his batting average up to .307 in 2017.

“They [first basemen] always want to talk,” the college graduate with a comparative literature degree said in an interview last week. “And it’s not that I don’t want to, it’s just… I don’t know, man. I guess I’m not really that good at small talk. They ask me how I am and I always want to think of a witty answer, but… I mean, I just got a single. Obviously I’m doing okay.”

Jackson doesn’t see his distaste for badinage as a problem, but does admit that it’s affected his game.

“For a while last year it got so bad I started doing that plane elevation thing I read about, just to see if I could hit more doubles. I just kept blooping in Texas Leaguers. Nothing worked. Every time I just wound up back at first. How do these guys remember stuff about my family? Like, I told one first baseman my dog was sick, and then everybody was asking me for a week how my dog was doing. Was there some kind of first baseman conference call? And why wasn’t I on it?”

“Besides,” he adds, looking down at his hands, “I can never tell. Do they want to talk about my dog? Or are they just trying to distract me so I get picked off? I want to be able to believe in people, but it’s hard, man. It’s hard.”

Jackson realizes that his .084 ISO isn’t ideal, either for a first base prospect or for an introvert. But he says he has plans heading into 2018.

“I’m gonna hit the weight room for sure,” he said. “And as for the other thing, well, I read Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance this winter. I’m just gonna keep telling people how interesting it is until they leave me alone.”

photo © Brett Davis-USA TODAY Sports

The end of the 2017 season marked the Atlanta Braves’ first full season in their new park, which they have now been at 1/16th as long as they were at Turner Field. When the Braves announced in 2013 that the team would be moving out of Turner Field and into a brand-new stadium in suburban Cobb County, Atlanta bucked a trend that had been in place since the 1970s of clubs moving closer to city centers. The Braves point to the need for a smaller stadium rather than the Olympics-ballooned Turner field, as well as a desire to be nearer to the majority of their season-ticket holders, the vast majority of whom live in or near Cobb County, which is mostly picking up the tab for the new stadium. One thing that wasn’t included in the move: a meaningful public transportation option. Cobb County voted against MARTA expansion in the 1970’s, and there’s no easy route to the stadium from Atlanta proper. (The Braves’ solution to locating SunTrust Park at the notoriously clogged intersection of two major highways? A partnership with Uber.)

After a slew of articles slamming the Braves for this move, pointing out issues of gentrification, accessibility concerns, and the general waste of replacing a stadium that would be barely old enough to drive, the general outrage went into cold storage over the next four years as the stadium was constructed. In 2016, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution revisited the issue, profiling Braves fans adapting to the move. One fan was Sister Marian, a Hawthorne Dominican nun who is somewhat of a legend within Braves fandom. A mention of her pops up as early as 1991, right at the beginning of the Braves dynasty of the 90s/early 00s; her picture ran in the paper the year after. Baseball will take every opportunity to highlight its nun fans, the irresistible juxtaposition of the sacred and profane, and Sister Marian–who administers hospice care to indigent cancer patients–is impossible not to love, with her baseball-themed apron and deep and abiding affection for the Braves. The New York Times profiled Sister Marian in 2006, after a transfer to St. Rose’s in lower Manhattan had pulled her far from both her family and Turner Field and her beloved Braves, as well as one unlikely friend.

In 1999, Bobby Dews, the legendary Braves bullpen coach, had detoured from his afternoon jog to visit Our Lady of Perpetual Help, curious about the iron-fenced home across the street from Turner field. Dews, who struggled with alcoholism over his life, found a “walking, talking inspiration” in Sister Marian’s compassionate care for her fellow beings, as well as the relationship the hospice had with the major league field across the street. In visiting Our Lady of Perpetual Help, Dews not only found the residents cheered by the nearby Braves, but found for himself a peaceful, meditative space, the kind of quiet mind-space that can be difficult to come by as an addict. “There’s probably not a day goes by that I don’t think about that home in some way,” Dews told NPR.

Dews passed away in 2015; two years before the Braves would move away from Turner Field, away from Our Lady of Perpetual Help. No longer can Sister Marian, who has returned from New York, walk across the street to see Braves games, wheeling some of her charges with her. Trips now have to be planned, coordinated, and will require a car; perhaps Sister Marian has an Uber account. The distance dims but does not entirely diminish Sister Marian’s enthusiasm, who told the Times in 2006: “Some people seem to enjoy things more than other people,” she said. “And maybe he gave me the ability to enjoy baseball more. You know? And I’m glad he did because I think baseball is the best sport there is.”

It just takes longer to get there now.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now