I have a request to make. Do me a favor. If you hear or read an announcer or pundit talk about the “lost art” of anything in baseball—contact hitting, stealing bases, intentionally trying to injure second basemen on slides, whatever—shoot me an email, OK? Let me know what you heard or read. If you’ve got a link, that’d be great.

The point is, I love people talking about Lost Art™. Because it’s mostly, you know, BS. The first time I wrote about this, last year, Cliff Floyd talked about the Lost Art™ of the two-out RBIs. I found no evidence of it. With everyone around baseball getting smarter, you just don’t get Lost Art™ absurdities the way you used to. Fire Joe Morgan went dark years ago. So we have to treasure the occasional Lost Art™.

I have SiriusXM in my car, and was listening to their MLB Network Radio station one morning when Eduardo Perez talked about the Lost Art™ of what he called “RBI Guys.”

RBI Guys, for the uninitiated (I certainly counted myself among their numbers), are batters who change their approach at the plate with runners in scoring position. They seek to make contact that’ll drive in runs. They expand the zone and shorten their swings in order to get the single or double that sends that runner on second base scampering across the plate. Perez gave an example of an RBI Guy: His dad, Hall of Famer Tony Perez.

As you can probably tell, there is a get-off-my-lawn element to this argument. Expanding the zone? That demand’s been made of Joey Votto and other patient hitters for years. Their critics claim they should be less selective, swinging at more pitches that they can put into play to drive in runners on base. Shorten swings? Power hitters like Aaron Judge get criticized for taking big cuts and going down on strikes, leaving runners stranded. (Somehow, 6-4-3 double plays with one out and runners on first and second don’t incur the same invective.)

So exactly how lost is the Lost Art™ of RBI Guys?

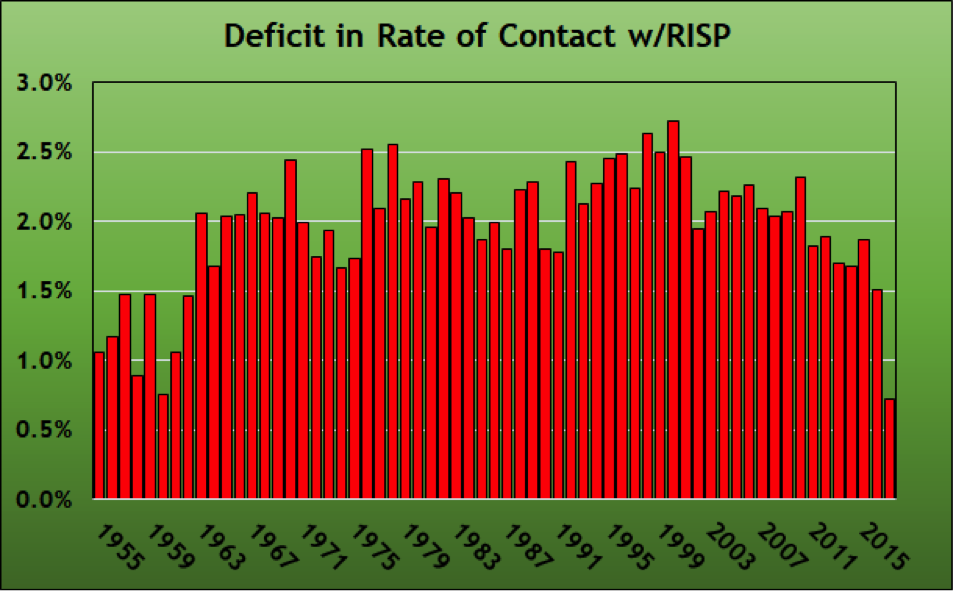

To determine this, I looked at the rate of contact by hitters with runners in scoring position compared to all other plate appearances. By rate of contact, I’m referring to all plate appearances that don’t end in a strikeout, walk, or hit batter, divided by all non-intentional walk plate appearances.

In 2017, for example, the rate of contact for all plate appearances (excluding intentional walks) was 69.2 percent. With runners in scoring position, it was 68.7 percent. In other plate appearances, it was 69.4 percent. So Perez was right: Batters had a lower rate of contact, by 0.7 percentage points, with runners in scoring position. They weren’t being RBI Guys!

But here’s the thing: That’s normal. Batters always have a lower rate of contact when runners are in scoring position. The reason is that walk rates are much higher with runners in scoring position. That’s partly because first base is often open and partly because the pitchers who face a lot of batters with runners in scoring position tend to be less skilled than those who don’t.

Last year, with runners in scoring position, batters struck out in 20.7 percent of plate appearances and walked in 11.1 percent. In all other plate appearances, they whiffed 22.0 percent of the time and walked 7.7 percent. Here’s the deficit in rate of contact for every season since 1955 (the first year with intentional walk data):

Far from being overly selective big swingers, batters this year had the highest rate of contact with runners in scoring position, relative to other plate appearances, in history. The average deficit (both mean and median) over the past 63 years is 2.0 percent. The deficit has been below that level in each of the past seven years. Far from being a Lost Art™, RBI Guys are more common now than ever before!

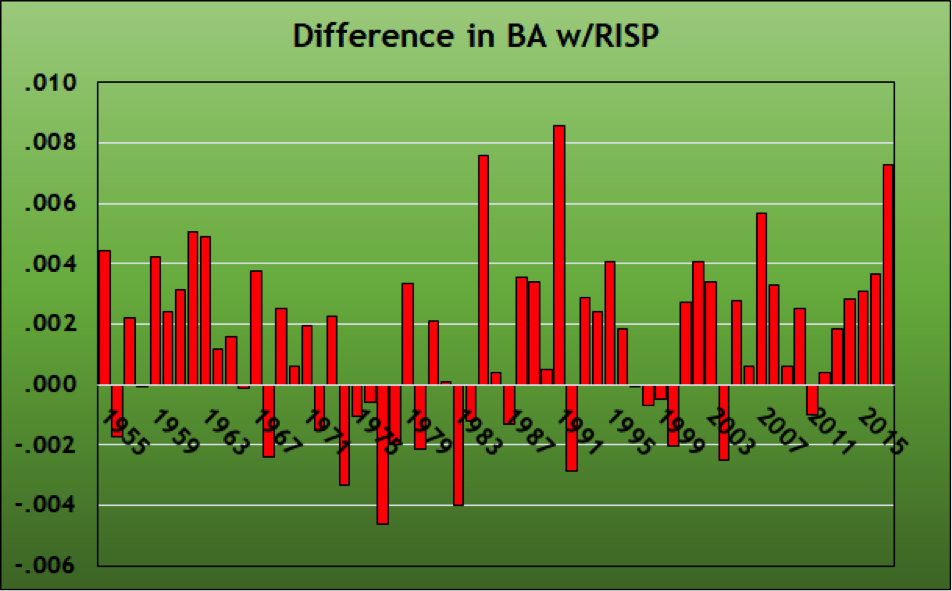

And that is borne out by the results. Below is the difference in batting average with runners in scoring position. Yeah, I know, batting average is flawed, but base hits with runners in scoring position are pretty valuable, since they typically result in runs. In 2017, 58.4 percent of runners on second base scored when the batter hit a single.

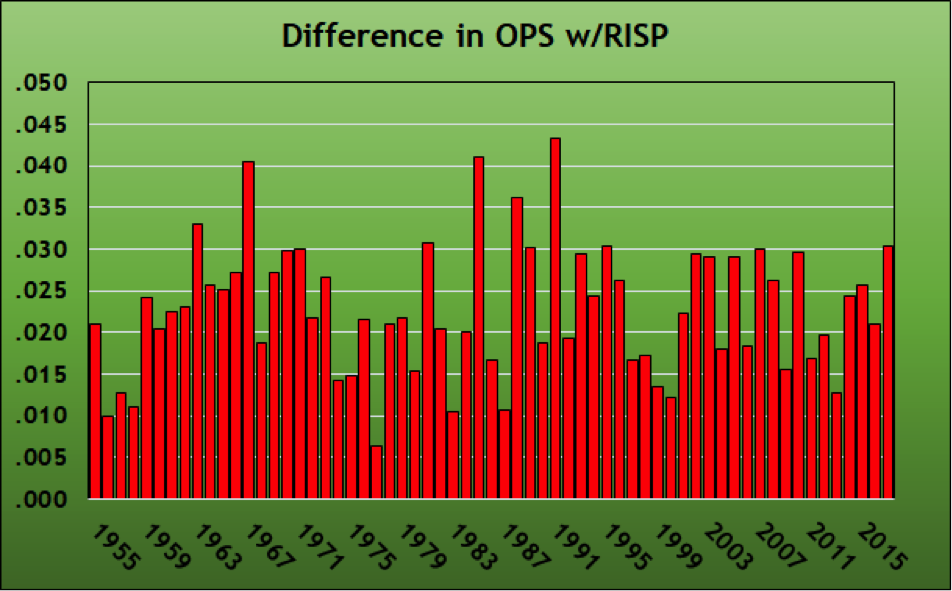

Or, if you prefer, OPS:

Perez’s timing was off. Yes, strikeouts are at all-time highs. And yes, a lot of batters are selective. Walk rates have risen for three straight seasons. But batters’ outcomes with runners in scoring position, relative to other situations, are at or near all-time highs. So Perez had it completely backward. Getting good contact with runners in scoring position is a found art, not a lost one.

***

And his dad, Hall of Famer Tony Perez? He was, in fact, a good hitter with runners in scoring position. He batted seven points higher, .284 vs. .277, with runners in scoring position compared to other plate appearances. That’s above average. He also slugged an above-average nine points higher, .470 vs. .461. And his OPS was a full 44 points higher, .834 vs. .791 (yes, 44, due to rounding).

And why was his OPS 44 points higher when his batting average was only seven higher and his slugging percentage only nine higher? Walks. Tony Perez walked a lot more frequently when there were runners in scoring position. He walked in 6.9 percent of his plate appearances with no runners in scoring position. That jumped to 12.1 percent with runners on second and/or third.

As a result, Tony Perez, RBI Guy, had a rate of contact that was lower with runners in scoring position than in other situations. The difference—1.5 percent, the gap between a 73.9 percent rate of contact with runners in scoring position and 75.4 percent without—is smaller than average. But it’s there. Perez was a good hitter with runners in scoring position, but it’s not because he shortened his swing (his strikeout rate was only 0.4 percent lower with runners in scoring position), and it’s obviously not because he became less selective. He was certainly an RBI Guy, but not for the reason his son attributed to him. He was not a practitioner of a Lost Art™.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now