The Wild West survives to present day as an important chapter of the American identity: a symbol for national adolescence, its spirit and its recklessness. The West itself has been largely paved over, and there are ghosts beneath the asphalt, but we still have westerns, still collectively try to capture that essence of having a frontier. It’s not easy to maintain that memory otherwise; even the movies and the cheap TV shows fail to convey the feeling of life at that point, of the cold and the anarchy and the injustice and the social mobility afforded by a lack of society.

Baseball similarly struggles with this. While, thanks to our old friend Hank Chadwick, we have a perfect history of what happened in baseball, we suffer for a lack of understanding of how: how it felt, how people thought about it. We have their sportswriters, and we have those sportswriters’ collective Hall of Fame ballots. But when it comes to even a simple question like “who was the greatest outfielder of all time?” it’s easy to forget that we lacked some of the simple tools we now take for granted.

There was no WAR; Win Shares first appeared after the Mariners made their last playoff appearance. The eighties were a time for smart baseball minds who were feeling around, asking questions, sometimes asking really bad questions. It really was the Wild West of baseball thought, a lawlessness and an almost unconscious understanding that something, something exciting, was just over the horizon.

Amidst this era, in 1987, Eugene and Roger McCaffrey shared two things: a love of baseball, and a direct-mailing advertising agency. Combining these two assets, they hit upon an idea: send an unsolicited survey to every living baseball player they could track down, collect the responses, and then use it to decide who the greats considered great. They mailed out more than 5,000 letters, and got back 645. From that, they assembled their rankings, by position, of the greats of baseball history, into a book, Players’ Choice, published fortuitously on the very cusp of the modern era.

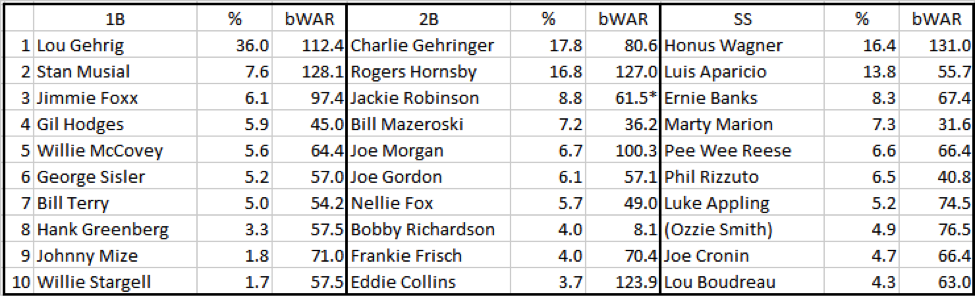

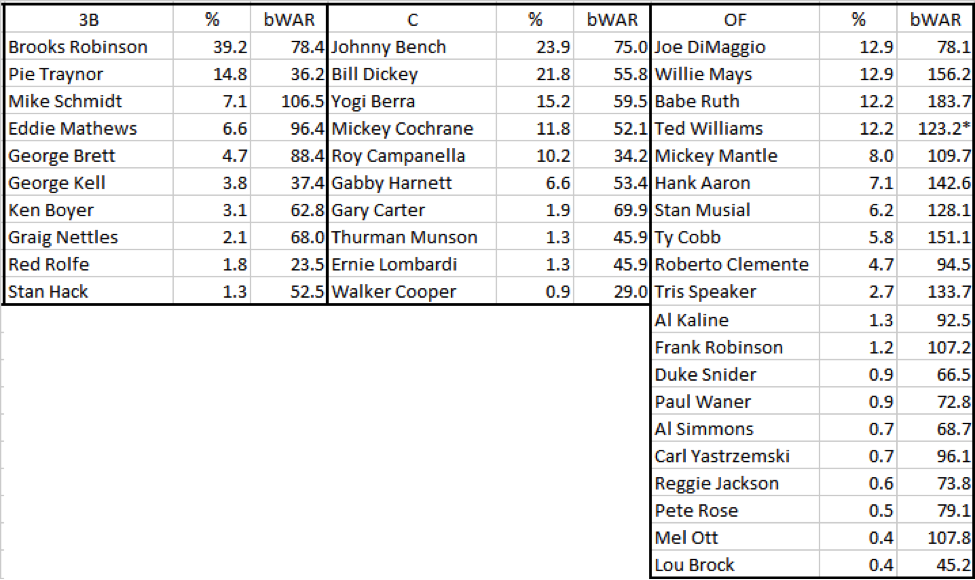

The surveys they sent out contained a number of questions (Should there be a DH? Who was the toughest out?) but for now, let’s take a moment to reflect on how baseball players judged baseball players, 30 years ago. (All calculations use Baseball-Reference WAR, with asterisks denoting careers cut short or, at time of publication, not yet into obvious decline.) The hitters:

The first thing one can take away from these results is that the players did a pretty good job overall. They have some foibles, sure, but so do sportswriters, especially ones of this vintage.

Tackling the trends:

- The greats of the 19th century were generally excluded. This will be more evident on the pitching side, where pitching statistics and their billions of games started per year translate better to today’s WAR calculations, but the selection bias is natural. People are going to lean on their own personal experience, and that means the best they played against. Everyone who pitched to Ross Barnes had long since shuffled off.

- Folks loved their Yankees. Another element of pre-internet history we tend to forget is just how local everything was. The players were obviously less susceptible to this than the fans, since they went and played everyone, but the nostalgia and folklore that built up around baseball tended to accumulate around the dynasties. In the way that MVP awards used to automatically go to the perceived leader on the team with the best record, regardless of production, Yankees get a lot of retrospective credit for being Yankees. The presence of names like Bobby Richardson, Phil Rizzuto, and Red Rolfe (and Allie Reynolds) below is one of the most predictable results of this exercise.

- For hitters, duration seems to have counted more than peak. Roger Maris, absent, is the notable example here, but in general players tended to consider the greatest hitters to be the ones who kept it up. Maybe it’s a reflection of the daily marathon of the position player.

- Multi-position players threw the voters. It’s not clear how the survey handled it, but players who fell into multiple categories tended to do worse in both. Pete Rose received votes at first base and third base, and surely would have finished higher in an overall ranking. Ditto Harmon Killebrew, who split between first and third.

- Baseball players themselves had no idea how to evaluate defense. Many of the players we would look at today as overrated on this list were defensive specialists: Bill Mazeroski, Ozzie Smith (only halfway through his career at publication), and Luis Aparicio. It also explains Gil Hodges, whom the voters considered far and away the best defensive first baseman of all time, over a decade of Keith Hernandez’s work. The McCaffreys, SABR members themselves, have their own doubts. On Brooks Robinson’s unquestioned role as greatest third basemen, they shrug: “Is Robinson’s big defensive edge worth 244 home runs?”

It’s a pretty good list, but we there are some obvious holes. Cap Anson falls under the 19th-century rule but seems famous enough, and the first base class weak enough, for him to make it; I’m okay he didn’t. Eddie Collins is embarrassingly low; maybe he didn’t bunt enough for the old-timers. Nap Lajoie is a surprising omission; I always associate him in that same class as Charlie Gehringer, Honus Wagner, and Rogers Hornsby, or at least right under them. He got forgotten. Rod Carew probably suffers from the multi-position curse and just misses the cut at second base.

Selection bias hurt modern-by-1987 players, so it’s not a shock that Robin Yount missed the cut, and Cal Ripken was only five years into his career. Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker are missing, but then, Whitaker still is. Ron Santo … well, it would have been surprising if Santo had gotten a vote. It’s a little crazy that Carlton Fisk can’t at least beat Walker Cooper. And while I’d like to be surprised at the lack of votes for Josh Gibson or other Negro League stars, we just weren’t there yet.

One last takeaway: one of the interesting things about disposable history books like Players’ Choice is they give you these random insights into the inexplicably loved things of yesteryear. Like Happy Days. Or Neil Diamond. Or Pie Traynor. The previous generation adored Pie Traynor—in 1976, Topps created a subset with The Sporting News to establish the greatest player at each position, and they went with Traynor even over the retiring Robinson. I don’t get it. I’ll never get it. It was apparently so obvious at the time that people didn’t even bother to debate it, so we can never even get the pros and cons. History is weird, man.

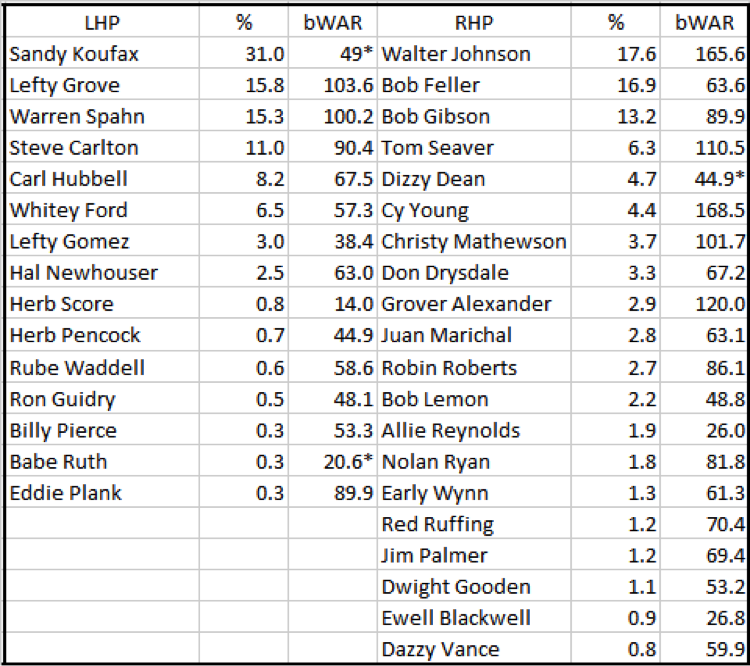

That said, moving on to the pitchers:

- When it comes to pitchers, peak trumps longevity. The presence of Herb Score on the list is proof enough, but two years of Dwight Gooden also reveal: it only takes a little time to scar a batter. Especially for right-handed pitchers, some of whom we would today consider the all-time greats—Phil Niekro, Bert Blyleven, Gaylord Perry, and Fergie Jenkins—didn’t stain the retinas the way that others did.

- We live in a silver age of left-handed pitching. Unlike with every other position, it was extremely difficult to find snubs on the left-handed pitcher list. You have to go all the way to Frank Tanana, who is pretty much the opposite of what the voters here are looking for. The eighties in particular are pretty bereft. And yet within a decade of publishing this book, we’d see a list of names like Randy Johnson, Tom Glavine, Andy Pettitte, David Wells, and Jamie Moyer, all of which could easily stand beside Herb Pennock.

- There was a baseball player named Herb Pennock. I double checked.

Is there anything to take away from this exercise? I think it’s clear that the existence of WAR has fundamentally altered the way we look at talent. Statistics are not the end-all, as many at the turn of the era feared; there still seem to be plenty of room for debate and conversation. But what WAR has done is reverse the order. Reading old baseball books, one thing that’s quickly noticeable is that discussion begins with legacy and is reinforced by statistics, whereas now the opposite is true; we look at their production and then adjust that total based on the extenuating factors. The rankings of Ty Cobb and Joe DiMaggio might today be reversed, simply based on the order of operations when assessing them.

I love books like Players’ Choice, not because it’s a good book or a bad one, but because it’s so clearly locked in its moment; reading the explanations for the votes feels raw and honest in a way nostalgia so often disguises. (Jim Brosnan, asked who his favorite baseball writer was, responded: “Jim Brosnan.”) Glimpsing through the thought process of a generation ago, seeing their biases and the lines of inquiry that went nowhere, gives us a reflection of our own pursuit for perfect understanding. For all of our analysis, we will also be wrong, sometimes Pie Traynor-level wrong. It’ll be fun finding out how.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now