The Fairness Doctrine

By: Emma Baccellieri

There is this idea that sports are like life. This is tossed around most often, it seems, when it comes to conversation around the relative merits of kids playing sports: They’ll learn life lessons. Because sports are like life! Justice and honesty and responsibility and respect and winning and losing—they’ll get all these complicated things, not as moral medicine to be force-fed but as games they already enjoy. It’s perfect.

Except it’s kind of wrong. Mostly wrong, even. Sports are not so much like life as they are like video games—something with clearly delineated marks for success and failure, with no grey area in between. You win or you lose or you tie, and you know by exactly how much, and exactly the rules by which those points or runs or goals got on the scoreboard. You know just how long you played and just when the next game will be and just whose mom is going to bring the orange slices. There is a cleanliness and order and a fundamental fairness in sports that is absent from much of life. You are not left wondering how, exactly, you were inadequate or if they thought you were kind of strange or whether she’s going to call you back. You know. You know what you did, you know how it measured up, you know when your next chance is. There’s injustice at the margins, sure—bad calls, scorekeeping mistakes, all of that. And there’s some more insidious unfairness underpinning the whole thing regarding who gets to play and how much they might have to pay to do so. (This part, actually, is quite a bit like life.) But, on the whole, it is fair. A zero-sum fairness is all that sports really ever aim for. A winner, a loser, a scoreboard, a directive to go home and try again tomorrow.

One of the ideas of fairness here is that the best team wins. Not every day, sure. That’s why baseball plays 162 games: to find the best team. And this, then, is why the playoffs can seem unfair—because they can’t play 162 more, so the best team can’t always win. This means that the system is less fair, perhaps, but more fun. After all, fairness, for all its virtue, is not always especially interesting. Randomness is interesting. But it’s not fair.

The playoffs are different in Japan. In Nippon Professional Baseball, the postseason is called the Climax Series. This is not only far less pretentious than the World Series but also way cooler. It’s also far more fair, at least in terms of hewing to the principle that the best team should have the best chance at winning. The best team in each league gets a first-round bye. The second- and third-best teams in each league play each other in a best-of-three series. And then the winner of that series plays the best team in a best-of-six series, wherein the league’s best team has a one-game advantage to start.

More fair for those who have already won the most, then. Grossly less fair for everyone else. Which, for some, is enough to make the whole system unfair, or, at least, less fair than MLB’s system. Or maybe there’s no zero-sum fairness outside the neat little self-contained world of individual games, because, really, everything’s a little unfair.

Kershaw Won; or, Man Let it Happen

By: Matt Ellis

Kershaw won. It was a commanding performance—11 strikeouts, only three hits—but all I could think of is the dream of the cyberneticians around the turn of the century.

First it was Bergson, and then the Bell Labs guys—Black, Jewett, and so on. They thought that the human body was a thing capable of being distilled into numbers and inputs and outputs, and they didn’t know the political stakes of what this ideology would bring: neoliberal theories of the subject, the body in history, political economy, so on and so on. Vannevar Bush wrote about a dream of a supercomputer that held all human knowledge, and now I check my phone to see who unfollowed me on Twitter; utopia isn’t a noun, it’s an adjective.

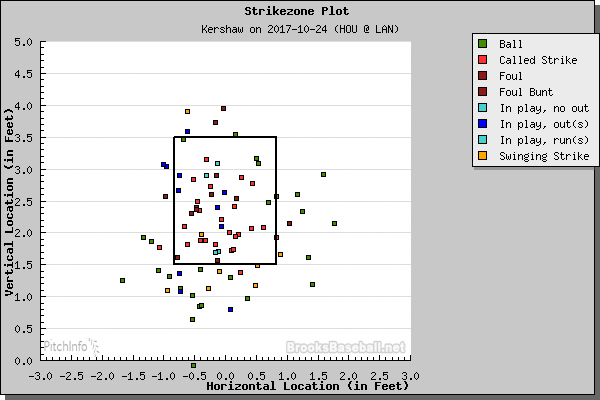

But still, Kershaw won tonight. He threw a whole bunch of strikes and they looked just… just beautiful. Here’s a picture:

You’ll notice the way that certain colors cluster in certain regions, as if to say that you’d try a curveball in the south while only a splitter makes sense in the pacific northwest. We still—I truly believe—don’t understand what this man is doing, and instead all we have are these graphs, but I want to imagine there is some way I can narrativize it here like this through a silly intro, in concert with a pretend contextualization in the history of cybernetics and computation.

The depressing part is that we told ourselves there is some great narrative we could understand through all this. I think about the way we want to demand robot umps at times, and then I watch what Kershaw did last night—an all-time great baseball performance—and I want to ask WHY do we want this?

It reminds me of what Florian Cramer asked in her influential article about the post-digital condition: demanding we disenchant ourselves from the fetish of technological magic to realize that sometimes some people just like plastic and inefficient cassette tapes, which tells us something about baseball, or at the very least, our experience of it. [1] That is, that, mannnn: A robot strike zone would be the worst thing that could ever happen, because we saw Kershaw at the peak of his game tonight. And when you put all the variables together—a pitcher at the top of his game, an all-time World Series—all of it: Why do you want to mess with anything at all, whatsoever!??!!?!

[1] Cramer, Florian, “What is Post-Digital?,” in New Media, Old Media, eds. Wendy Hui Kyong Chun and Anna Watkins Fisher. Routledge: New York. 2016.

Doubt the Dust

By: Jason Wojciechowski

I’ve read about 15 pages of John Fante’s 1939 Los Angeles Depression novel Ask the Dust, so, seeing how the Los Angeles Dodgers are in the World Series and all of us are in a deep depression, I think it’s not too early to think about how Fante’s recurring protagonist, Arturo Bandini, relates to baseball.

Or, more accurately, how he does not. Bandini is a struggling writer, where by “writer” I mean “someone who once wrote one thing,” living off the charity of his Colorado mother, who sends him occasional dollars; the glorious affordability of Southern California citrus; and the odd stolen jug of milk. He’s delusional about his talent, but there is also a vein of self-loathing and a strong inclination to give it all up, leave his Bunker Hill apartment building, and go back home to help his parents through the tough times. His stomach hurts.

We may see ballplayers like this, but I suspect that we generally only see them when we visit the outposts of professional baseball, the A-ball towns in the deserts and the forests and the suburbs of America. The ones who reach the major leagues are the confident ones, the blissful ones, the ones who live outside their heads, in a world of pure performance, of pure doing, not analyzing, not doubting, not worrying. It’s easier in athletics than writing, of course―even the most instinctive, de-intellectualized writers would have to admit it’s still an intellectual exercise, especially compared to pitching a baseball―but still, at core, here’s the question: Is failure failure, or is failure an opportunity to do better the next time? Bandini says one thing, Kershaw another.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now