When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child

A few months ago I stopped by a Little League field somewhere in the Northwest Hills of Connecticut to watch a friend’s grandson play some 12U travel ball. If you are concerned this is going to turn into a scouting report, I remember very little of the details of the game, other than the intermittent summer showers and some rather aggressive parental grousing about the strike zone. Watching the pitcher warm up on a basically flat dirt mound amongst not-so-freshly mowed grass, I was struck by an intensely powerful memory, a smash cut, Super16 flashback in the world’s most inconsequential Direct-To-Video sequel to The Trouble with the Curve.

I’m 12U, practicing my throwing mechanics in a Catholic Church parking lot in Wethersfield, Connecticut. It’s early March probably, the sky is a deep blue, the parking lot lights on. The snow hasn’t melted from the actual Little League fields yet so this is where we practice.

Break…and throw.

Break…and throw.

Break…and throw.

I fervently believe you don’t become a prospect writer, and certainly not a good one, without an ardent, devotional love for the game. There’s not enough money in it, and not enough prestige in it. To want to break the game down to its hundreds of component parts and put it back together—like a highly detailed 1:24 model of a vintage airplane—well, love is wiser than wisdom as Umberto Eco wrote.

My Little League coaches were Mr. Pasternak and Mr. Harris, who—from my admittedly limited frame of reference—were about the best coaches a 12-year-old could ask for. My otherwise hazy memory of this time is tinged throughout with their joy for teaching the game. I had the usual tween aspirations to be a major league player someday, but baseball writing was never even a stray thought. I was more enamored with the idea of being a lawyer because my grandparents usually had Matlock on the TV when i got home from school—usually just in time to see his climatic cross-examination of the real murderer.

But then again becoming a lawyer is just step one on the path to becoming a baseball writer anyway.

Eat It Up

As a devotional baseball fan, we of course look to spread the good word, and our children end up a captive audience. Mine is presently more interested in Abby Cadabby and Peppa Pig than baseball, although she is excited by the hats and constantly trying to get a hold of my bobblehead collection. We did take her to her first game this summer, which while not planned as such, ended up being my last trip to see the Yard Goats. It was a brutally hot and humid Sunday afternoon game, and I did not have the benefit of the party deck awning that covers the scout section from the worst of the midday sun. We got her picture taken with the ultramarine goat mascot—believe that one is Chew Chew—and she made it to the seventh inning stretch (god bless the pitch clock).

Like her first couple birthday parties and Christmases, this was more for the adults than the kid. She’s not making memories, but the ritual is important. I’ve referred to the baseball stadium as my office before, but others may consider it a cathedral.

My father, a lapsed Catholic, considers himself a Zen Pantheist because he communes with nature and the whole of creation by golfing on Sunday. A Fortune 500 flunky might condescendingly call this his version of mindfulness, but to me it sounds more like Tom Robbins ghostwritten by Rick Reilly, and well, that’s my dad.

I got married in an Episcopal service despite a Facebook: It’s complicated relationship with organized religion. I just liked the text in The Book of Common Prayer that I idly thumbed through at Little League age while not paying attention to the sermon.

My child will need to derive her own meaning in our fleeting existence, pick her own religion. I hope she chooses baseball.

I Can’t Get No (Short) Relief

Six days, 2200 miles, a series of pet-friendly hotels and local delivery places, white knuckling across the continental divide while getting passed at 80 mph by FedEx double tractor trailers swaying in the wind.

All to end up in a very similar seat watching a former fringe pitching prospect and occasionally successful major league reliever pump 95 mph fastballs that got lined back at 100 as the Wasatch range fades out of sight behind shades of deeper and deeper navy. The game grinds to a halt like so many games before it. I’m not running away from anything, but you can’t escape minor league bullpens anyway. Sometimes I look out my window and the mountains feel like they have crept a few miles closer. All the addresses here are an inscrutable string of numbers and cardinal directions, but you can always find your way to a 95 and a slider reliever having a bad command night.

Wherever you go, there you are.

Felted

Tales of bad beats at the poker table were already passé long before I started writing about prospects, but I don’t remember ever winning a coin flip with my stack on the line. I’m sure I did, and there’s probably a RadioLab episode about how memory works that explains why I can’t with a jangly minimalist electronic composition pulsing underneath it. Anyway, I was never playing for more than 1/2 no limit, or in the occasional competitive, but mostly jocular multi-table home tourney.

Disclosure: The author of this piece does occasionally chat with Trevor Hildenberger socially.

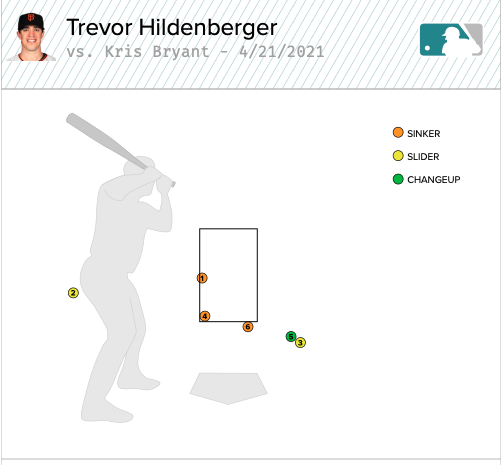

A fairly nondescript at bat in the middle of a cold and windy April blowout in Wrigley. Pitch number six is a 3-2 fastball with two outs and a runner on. If you squint you can almost see it catching the bottom of the zone.

It’s a coin flip.

As you’d expect, the MVP with the 11% career walk rate gets the call. Anthony Rizzo walks behind him, and a 1-1 slider to Javy Báez gets a bit too much of the plate. Hildenberger is optioned the next day, comes back for a week in May to sit in the bullpen watering tomatoes, and then is DFA’d without throwing another major league pitch. He is claimed by the Giants and tears his UCL later in the Summer.

The Mets used 25 relievers in 2021. Perhaps Hildenberger gets a few more looks if he gets that strike call and gets out of the inning and doesn’t have a 15.00 ERA when Sandy Alderson is sorting his pitching staff pivot table in Mid-May.

There’s always thin margins for a reliever at the end of the 40-man roster. Maybe Hildenberger finds something and gets a few more big outs. Blows out while he’s still on the major league roster. There are bigger stacks riding on some coin flips.

I caught him last week on rehab with Sacramento at the end of a very long PCL season. Slider looked sharp, the intermittent command struggles to be expected for pitcher in his fourth inning off Tommy John. With first and second, and one out he induces a medium depth fly ball to left field. Austin Dean catches it, the runner tags, perhaps just to draw a throw. He gets one as Dean turns and heaves it onto the left field berm as every other River Cat’s arms get thrown up simultaneously, incredulously. Powerless to stop what unfurls in seeming slow motion.

Sometimes the one outer gets you too.

The stakes here were lower. A late-season Triple-A game with all the energy of an off tune classical dirge.

I’m sure this isn’t the first time I’ve referenced the Bill James decades superlative of “Can I try this career over?” from his most recent Historical Abstract, so I’m aware of the self-plagiarism. This column feels repetitive already, but it’s not mere cryptomnesia. You can run out of things to say after 10 years of prospect writing, even if you’ve never seen a player throw the ball into the stands with two outs in person before.

I wonder if Hildenberger would like to try that inning against the Cubs over. I’d argue his career is perfect as it is.

“If I can say I played a small role in helping unionize the minor leagues—that’s way cooler than pitching in the big leagues,” Hildenberger says. “This is by far the thing I’m most proud of. I think this will have a lasting impact on players, hopefully for decades and decades to come, thousands of people and their families. It’s just awesome.”

Author Surrogate

I think if you were to pinpoint the main trend in baseball writing, and certainly fandom, since that last Bill James Historical Abstract, it would be “parasocial relationship with the front office.” Or to put it another way: “rooting for spreadsheets instead of rooting for laundry.” On one level this was a response to a baseball media unwilling and unable to engage with the changes in the way the game was analyzed and even played. On another, the increasing pool of fantasy baseball players in highly specialized leagues, a readership market filled by an ever-increasing pool of touts with @roto in their twitter handles talking about what prospects they have “shares” of. And here’s yet another: Paths into major league front offices were democratized—I can just point to 20 years of BP writers getting baseball jobs and even ascending into high-ranking positions—so you were more likely to have chatted online with your favorite team’s 2VP than number two starter.

Admittedly, identifying with the players is tricky. High-end baseball talent is strange and unknowable. If you merely fail at your job six out of ten times you are elite, a concept perhaps a bit foreign to your run-of-the-mill air traffic controller or roofing installer. It also perhaps leads to some weird mindsets, even moreso is you are a high-level starting pitcher.

As a prospect writer this gets even thornier. We root for our evaluations to be right, maybe. For our “acquire 3s” to make it, perhaps. But you can never really identify with the prospects. We all have types of players we like to watch though.

Cesar Valdez started the second-to-last game I saw this season. He threw almost two-thirds changeups—which is low for him—works quickly and throws strikes. I’m not obligated to take shorthand on a 37-year-old with 16 years in pro ball, five in the majors scattered amongst a baseball-reference page that won’t fit on my 22” monitor. But I feel an affinity with the wandering swordsmen of baseball. Or at least find it charming. As one scout said to me: “He can get outs.” It is a long Triple-A season. It’s an even longer prospect writing season. But Valdez will show up to the park to try and get outs while sitting 85, then so will I.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now