This article was originally published on February 22.

Welcome to a very small club, Wander Suero.

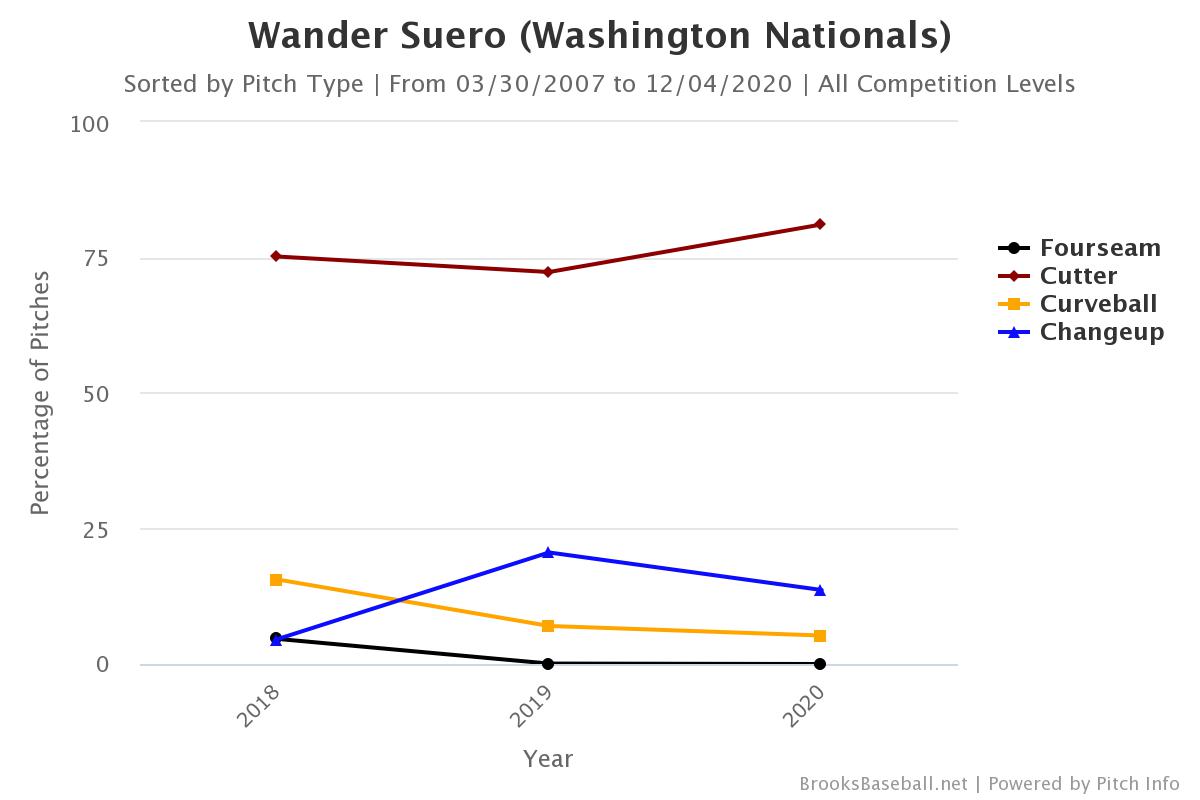

Suero, a Nationals reliever, threw 381 pitches in the 2020 season, 81 percent of them cutters. And if we agree to the somewhat arbitrary definition that throwing a single pitch type 80 percent of the time or more makes one a single-pitch pitcher, this puts him in a fairly exclusive group.

The fraternity of current one-pitch pitchers contains familiar names: Suero’s former teammates Sean Doolittle and Trevor Rosenthal, Jake McGee, Kenley Jansen, and Zack Britton. Each of them has a signature pitch. For Doolittle, Rosenthal, and McGee, their four-seamers. For Suero and Jansen, their cutters. Britton stands alone as the sole sinker-throwing one-pitch pitcher. (Please say this five times fast.)

But are they really as monogamous with one pitch as their reputations insinuate? If you’re not literally Mariano Rivera, it’s hard to keep throwing one-ish pitch over long periods. Hitters get wise to it. The juiced-ness of the ball changes—so a pitch that induced a lot of flyball outs might not be the best pitch to throw if the ball is particularly lively. Pitchers age and their velocity declines, so they have to do what the rest of us do: get by on treachery and finesse rather than youthful enthusiasm.

Many of Suero’s one-pitch contemporaries have moved into throwing a secondary pitch more frequently as they’ve aged. Call it the ‘seven years in the majors’ itch. Is that the future fate holds for the 29-year-old What follows is an illustrative, not exhaustive, review of one-pitch pitchers (and those billed as one-pitch pitchers who actually aren’t).

It’s no surprise that Suero has increasingly leaned on his cutter. Batters averaged only .222 off that pitch in 2020, and lefties, against whom Suero previously struggled, hit a mere .167. In comparison, they averaged .354 against the same pitch type in 2019. His whiff rate has similarly increased from 12 to 17 percent over the past three seasons.

Somewhat counterintuitively, he became more effective even as his cutter’s velocity decreased, as did the velo on his changeup, his main secondary pitch. But perhaps his efficacy has come not from the velocity itself but the differential between his cutter and change.

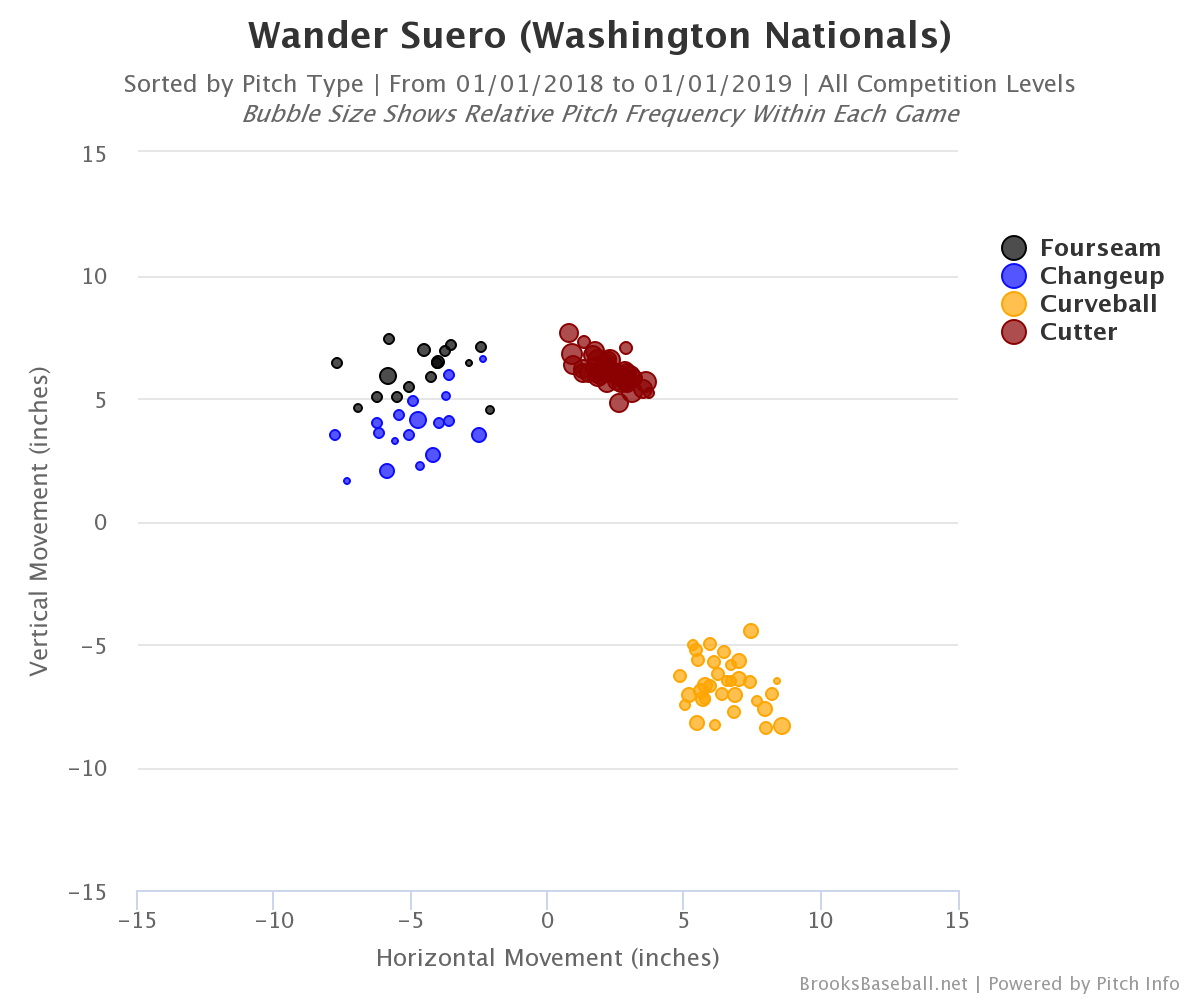

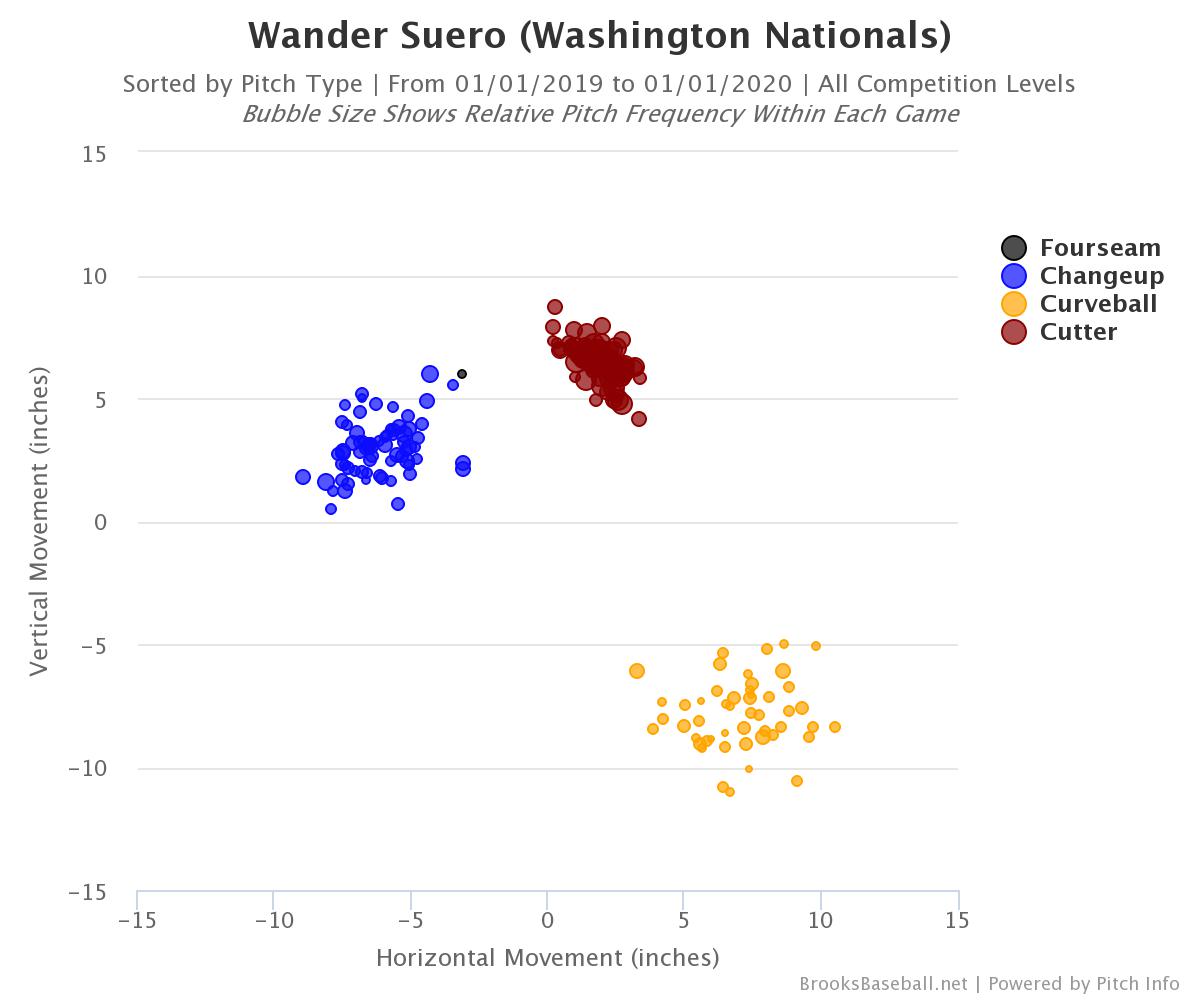

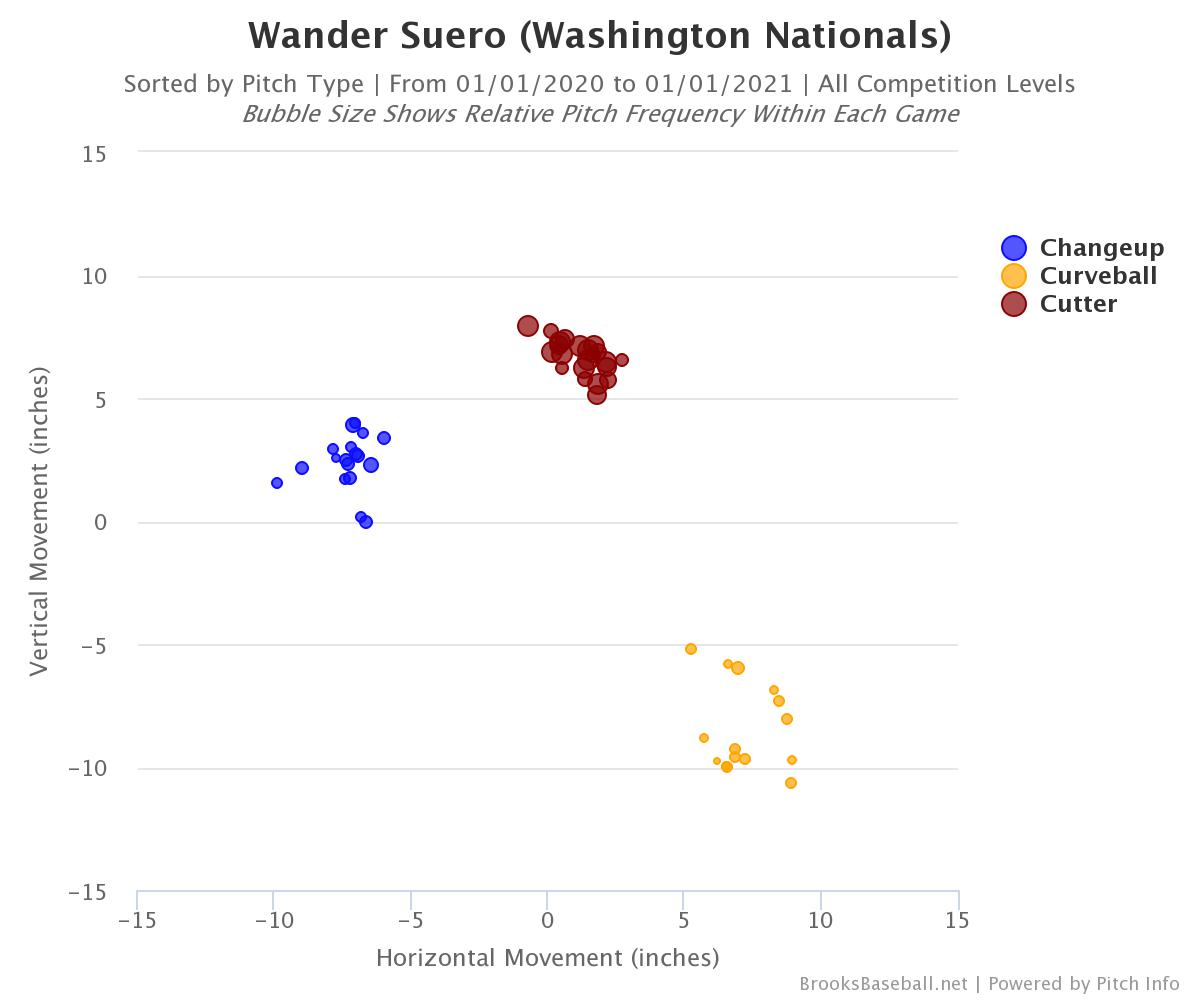

Differences in velocity translate into differences in timing. If a pitch is thrown to a similar location and with a predictable timing, hitters know how to meet it. So, Suero has, fairly subtly, distinguished between the two pitches, both in timing (as shown in the table below) and in space, with his changeup clustering more discretely from his cutter.

| Fourseam | Change | Curve | Cutter | Cutter- Changeup Velo Difference |

|

| 2018 | 92.49 | 88.65 | 79.74 | 92.17 | 3.52 |

| 2019 | 94.46 | 87.77 | 79.73 | 93.15 | 5.38 |

| 2020 | 0.00 | 86.69 | 77.46 | 91.51 | 4.82 |

Is this sustainable? He’s the only current Mr. One Pitch under age thirty (though, he’s 29), and the others have been forced to retool their approaches as they’ve gotten older. Still, Suero having a secondary pitch that can draw whiffs and elicits few extra base hits (even if it’s hit more frequently than he might like) may enable him to exist as a one-pitch pitcher longer than his brethren.

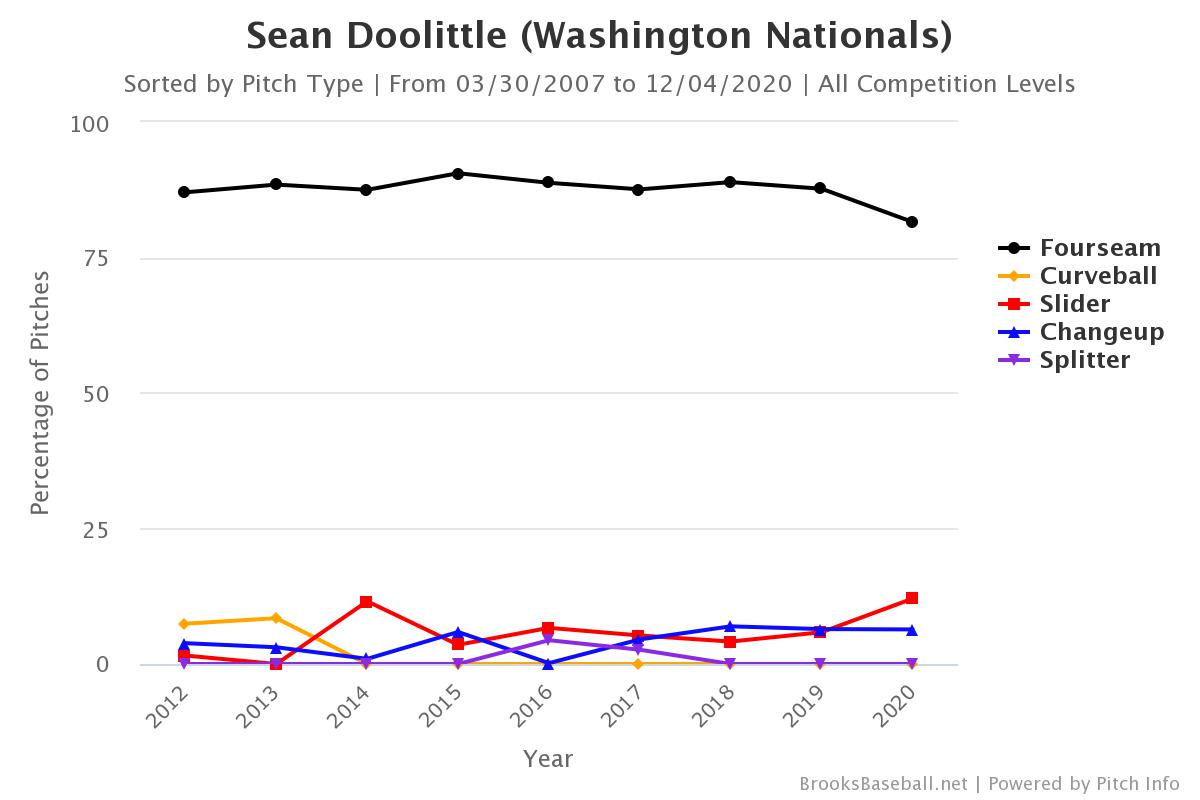

Sean Doolittle

It is a truth universally acknowledged that an aging pitcher in possession of a fastball with a declining velocity must be in want of a secondary pitch. Doolittle has developed and abandoned a number of pitch types over the years to supplement his four-seamer, including a slider that he threw for a career-high (of any secondary) 12 percent of pitches in 2020. This shift was motivated in part because of a sharp decrease in the velo on his four-seamer, something which Doolittle worked to retool mid-season before being sidelined by an oblique injury, and has continued to address in the offseason.

And as a flyball pitcher—Doolittle produced exactly zero ground balls in 2020—he may need something to induce more worm-killing contact in Cincinnati, since the Great American Ballpark has, despite the name, one of the smaller dimensions in the league. (As a note-slash-fun fact, Doolittle’s feat of producing zero ground balls over 127 pitches thrown in a season is the most thrown for a zero ground ball percentage since tracking began in 2002, per Fangraphs.)

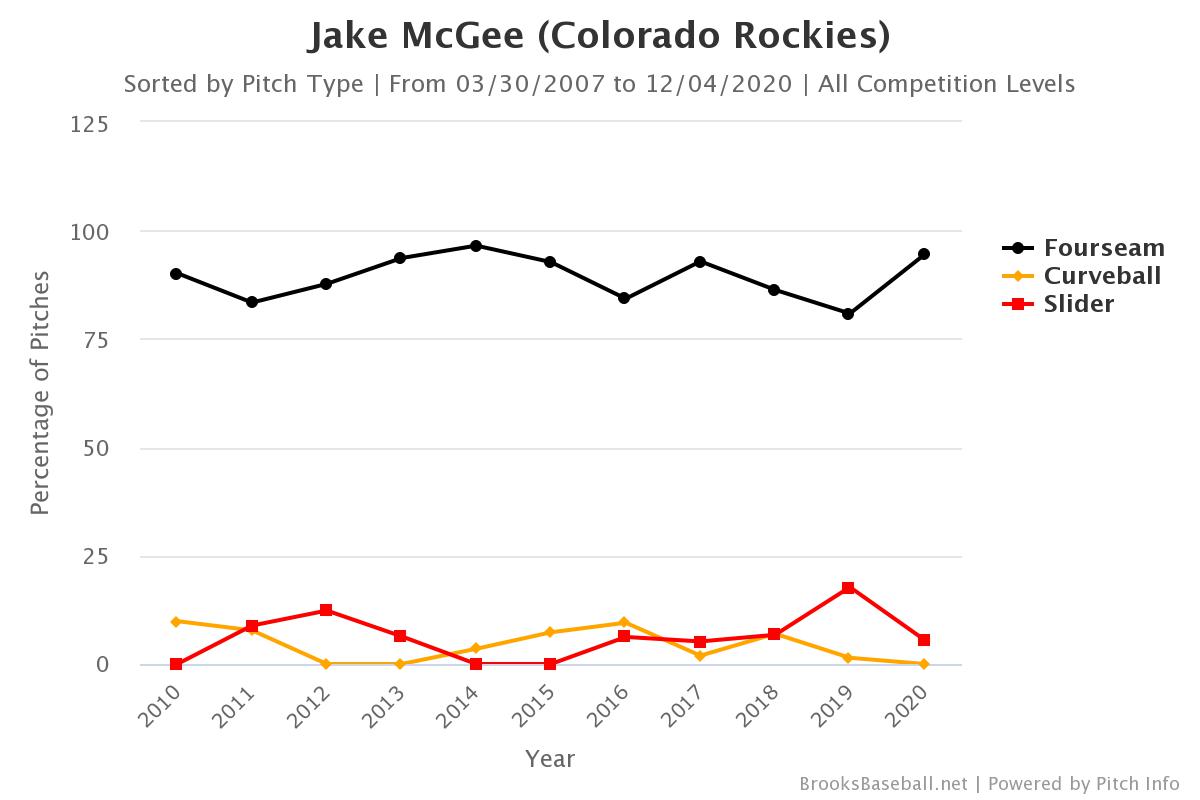

Jake McGee

Of all the members of this fraternity, McGee comes the closest to being a true one-pitch pitcher, throwing a high-nineties fastball that has, in recent years, seen a tick or two peel off its velo. It’s perhaps not a coincidence that he paired a career-low average velocity of slightly under 94 with career-high slider usage in 2019. He also threw his slider 11 percent of the time when his fastball averaged 96 in 2012. However, he had a greater velocity differential between his fastball and slider in 2019 than in 2012. Hitters struggled against the 2019 version of the slider, with a .143 BAA even as they feasted off his fastball.

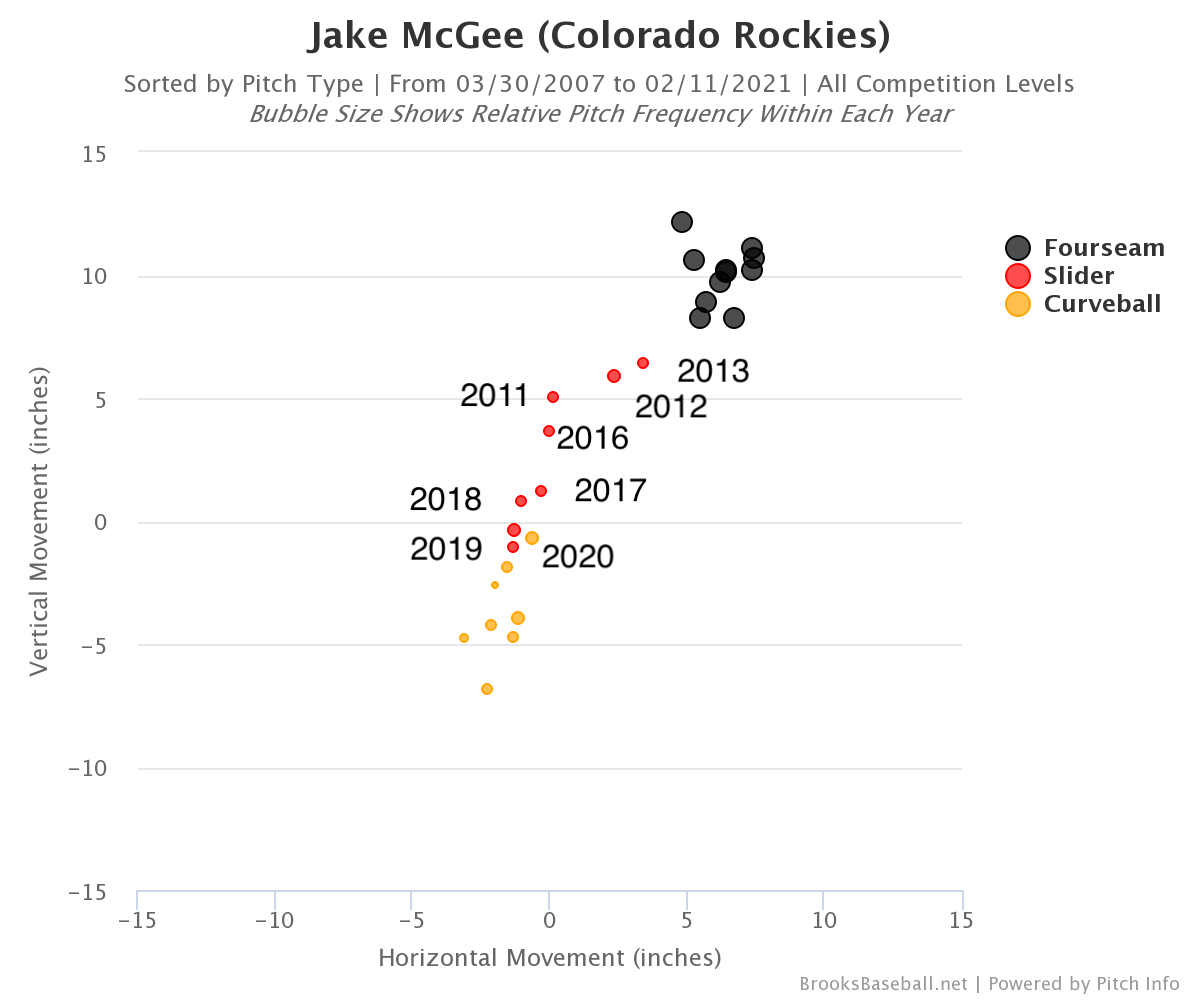

His slider has also evolved over the course of his career, becoming more distinct in time and space from his fastball. My first reaction to the subsequent chart was literally “what the heck is going on with that?” since the breaking ball’s placement has sauntered vaguely downward—the slider has bled velocity as it gained break. The bubble size shows the relative pitch frequency each year, reminding that he generally threw relatively few sliders compared with his fastball. Still, as someone who spends a lot of time staring at Brooks’ scatter charts, it’s somewhat unusual to see the graphical representation of a pitch’s development. Having a developed secondary pitch, even one he doesn’t use particularly often now, is an insurance plan for when his fastball does what most of us when we hit our mid-30s: slow down.

Unlike almost everyone else on this list, Britton wasn’t always a one-pitch guy. Suero might be inducted into the club this year, but he was knocking at its door for the two previous seasons. Britton, on the other hand, did a full-tilt revision, going from having a fairly typical pitch mix to being an exclusive sinkerballer.

But how that transition took place is somewhat noteworthy: Britton developed a curveball in 2013 before becoming a one-pitch guy (or a 1.5 pitch guy), and then abandoning his four-seamer, slider, and changeup. And he’s thrown that pitch, which is a slurvy breaking ball that we’ll designate a curveball since Brooks does, more frequently since leaving Baltimore in 2018. (Because who amongst us hasn’t thrived after leaving a relationship where we perhaps didn’t feel valued?) So, again, better to have a developed secondary pitch and not need one than need one and not have it—especially if that pitch can draw whiffs to supplement a sinker generating ground balls.

Rosenthal’s inclusion in the one-pitch pitcher club is by the slimmest of margins. He tossed fastballs more than 80 percent of the time in 2012, but incorporated at least one secondary pitch used more than 10 percent of the time each subsequent year. He has largely retired his curveball, but has increased use of his slider, tossing it more than 20 percent of the time the past two years as he sought—as a Nationals’ 2019 bullpen disaster and then the Padres’ closer—to remake himself following a missed 2018 season. Unlike the other members of the one-pitch club, Rosenthal hasn’t experienced a decline in his velocity as he’s aged, with his four-seamer averaging above 97.5 mph in all of his last eight seasons.

He also uses his secondary pitches as his putaways: since his return from Tommy John surgery he’s tossed his slider more than 30 percent of the time when he’s ahead or on two strikes to righties. So, like his inclusion in the Nationals World Series narrative, his inclusion here should be with a fairly heavy asterisk.

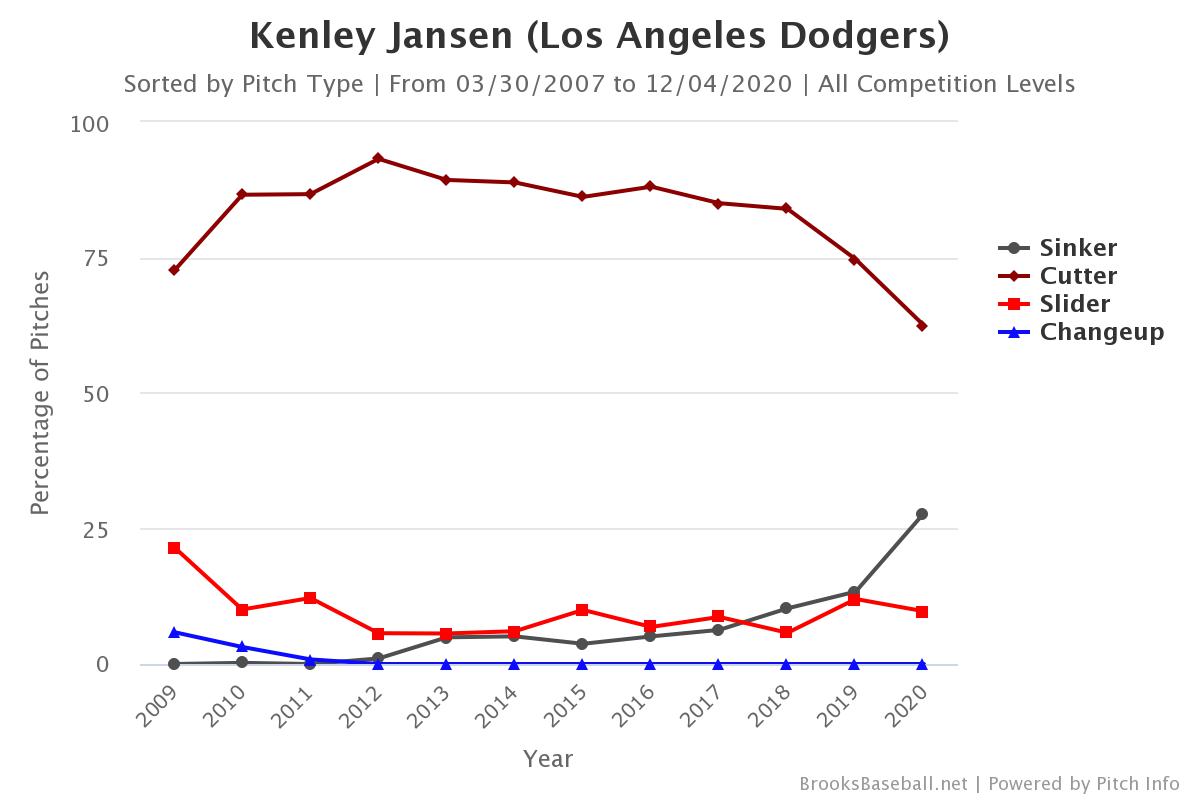

Kenley Jansen

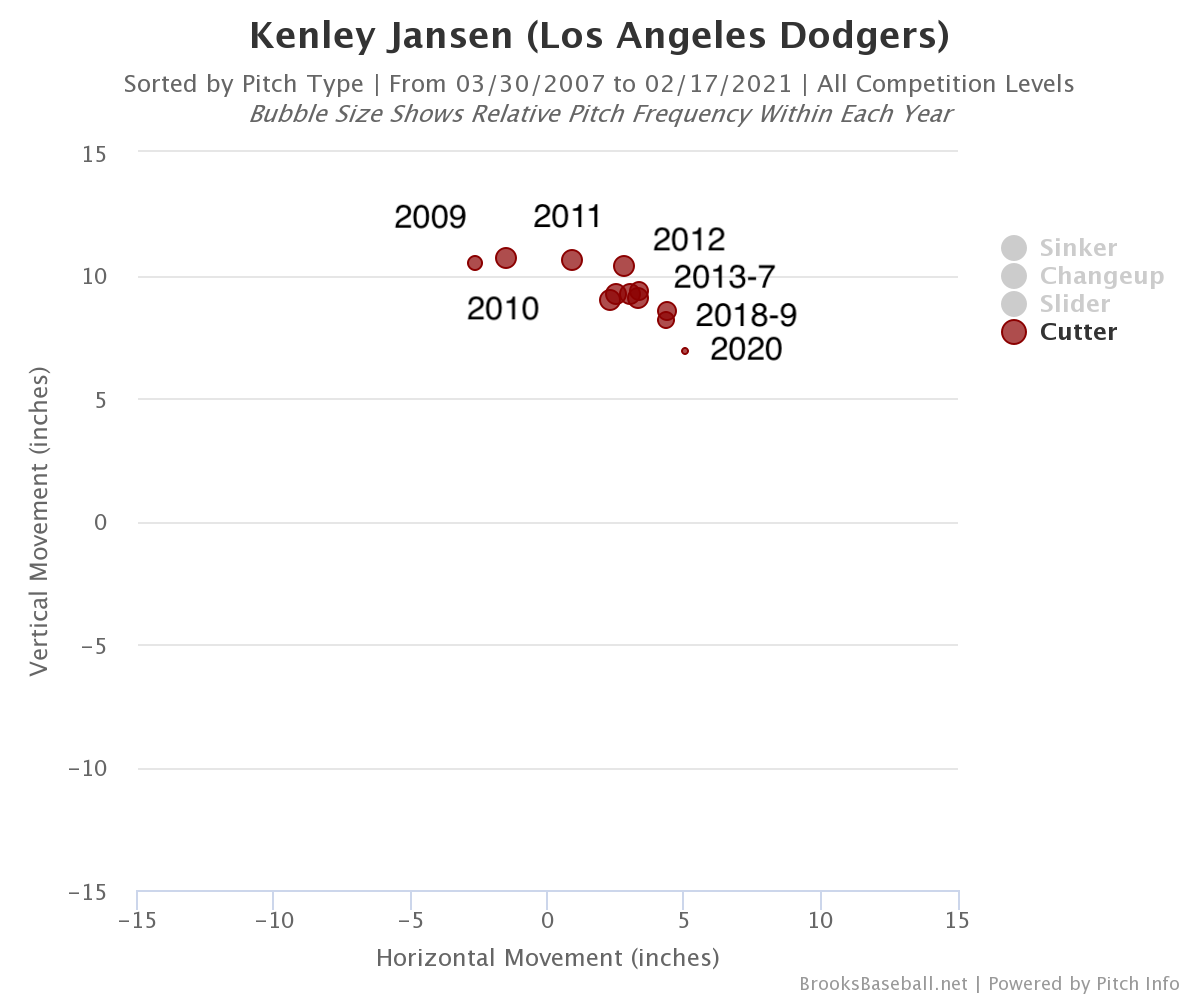

Jansen might also be a member emeritus of this club. After tossing his signature cutter more than 80 percent of the time every year between 2010 and 2018, Jansen has had to turn to other pitches—his slider and sinker, primarily, as hitters are able to make significant contact off his cutter.

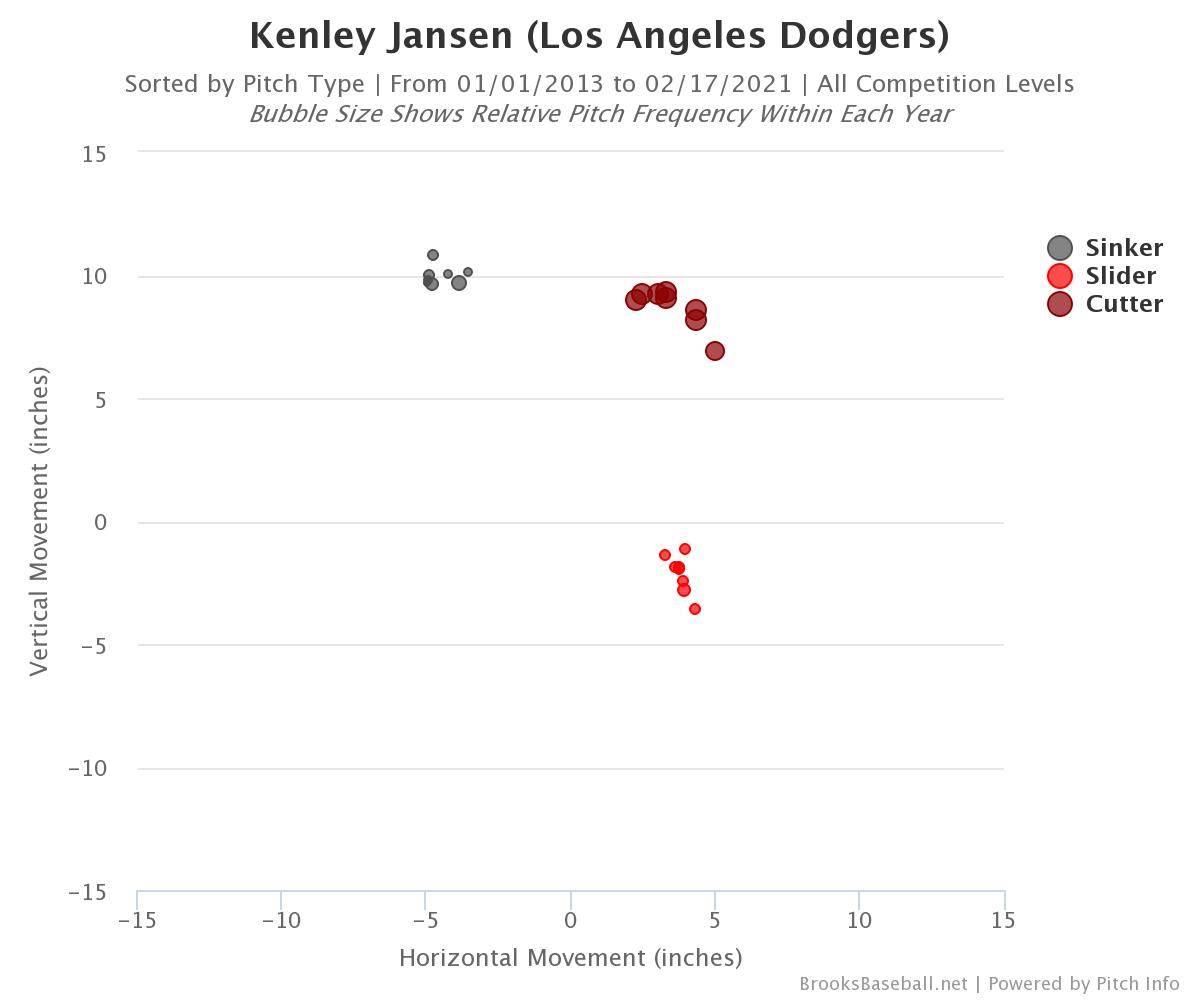

Aging, of course, takes its toll. As Jansen’s cutter velocity has decreased, he has publicly discussed the challenges of needing to go to his secondary pitches. However, Jansen actually may have set himself up for success through adjustments he made to his cutter years ago. Like McGee’s slider, Jansen’s cutter has gone on something of a journey over his career before settling into the location where it’s remained more or less since 2013 (though it appears to be on the move again as of 2018).

However, if we just consider Jensen’s pitches since 2013, the year he started throwing his sinker with any sort of frequency, it’s obvious that, by shifting his cutter over, he’s able to throw his sinker in a way that’s distinct in time and space. So previous work in developing a secondary pitch when he needed it less may have allowed him to exit the one-pitch club more gracefully than he would have otherwise.

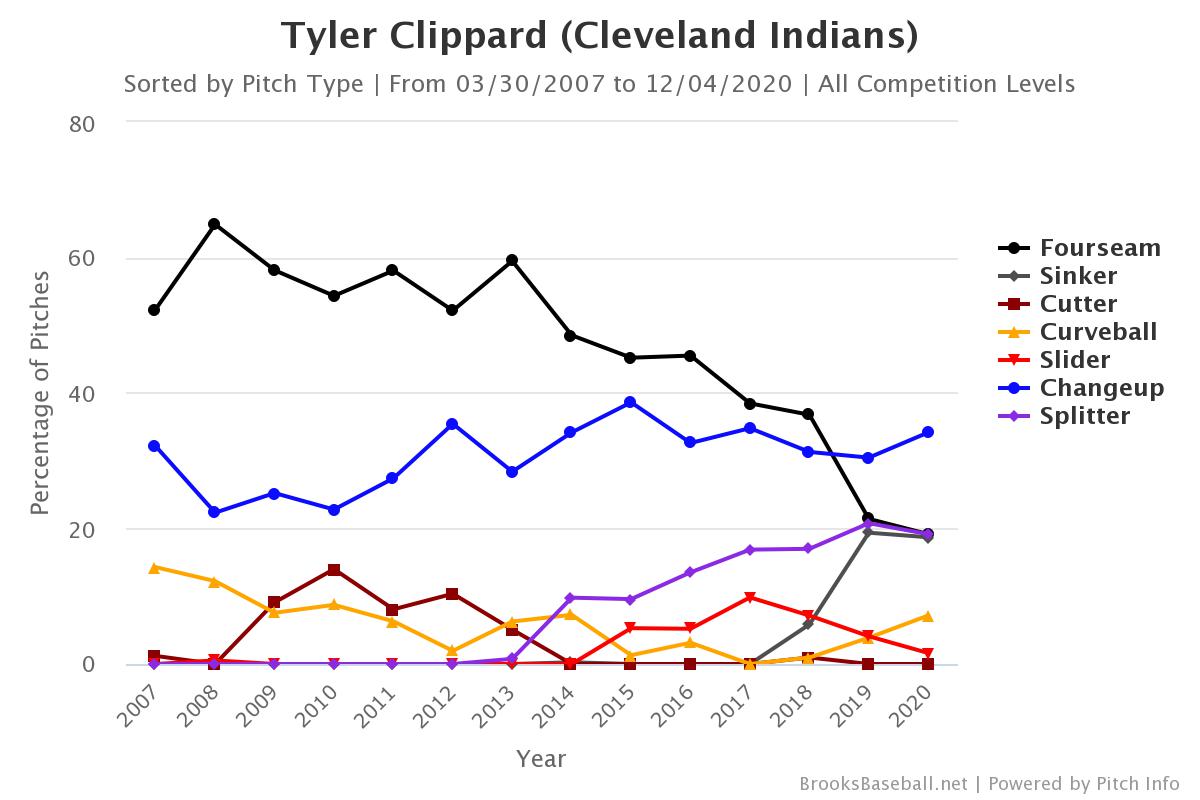

Tyler Clippard

Before you panic: No, I do not believe Tyler Clippard is a one-pitch pitcher. Clippard began his career as a starter with the Yankees, reinvented himself as a reliever and has been a fixture as the best random bullpen guy you probably aren’t thinking about (unless you’re me) for the past ten years. He’s never approached Mr. One Pitch territory, so exists as a control group of sorts. Clip deployed his fastball, sinker, and splitter in almost equal proportions in 2019-20, because at a certain point (usually your mid-to-late thirties) craftiness eclipses stuff.

***

In ecology, the biodiversity of an ecosystem is a product of two different components: richness (the number of different species) and evenness (how close in numbers each species is in a given environment). One aspect of evenness is the likelihood that if you select an organism from an ecosystem at random, how likely are you to get an individual of the same species if you make another random selection. The more even the ecosystem is, the less likely it is that the second time you make a selection, you get an individual of the same species as the first.

So, to extend a metaphor (and acknowledging that pitch selection isn’t a random process), Clippard’s high evenness of his pitch mix makes it difficult for hitters to anticipate what he’s going to throw, notably avoiding a predictable out pitch even when ahead in the count, and therefore has provided a key component of his longevity.

In ecological diversity indices, evenness is generally presented as the converse of dominance. So, if McGee has a pitch ecosystem dominated by one pitch (think a Christmas tree farm), Clip is more akin to a deciduous forest.

Biodiversity generally serves as a key component of ecosystem health because it can be predictive of an ecosystem’s resistance to, and resilience from, change. If a blight attacks a Christmas tree farm, every tree is susceptible. If the trees go, so goes the forest. To mangle a metaphor, there goes your career throwing only high fastballs. But in a diverse ecosystem, there are more safeguards against disturbance, whether it be an increased number of tree species or a curveball. So, it’s risky being a one-pitch guy in a pitch mix world, because the world changes and you have to change along with it.

How do pitchers select and develop a second pitch? If the why is clear: that you need a secondary pitch to play off the primary one, the how is less so. How, for instance, did Zack Britton move to throwing a slurvy breaking ball to pair with his sinker?

The short answer is that pitchers iterate constantly but are constrained by their motion. Delivery angle, as Harry Pavlidis and Dan Brooks argued in the 2015 Annual, determines pitch movement. Delivery angle is actually the construction of a number of other angles: shoulder abduction, elbow flexion, various trunk-tilt angles. In other words, and somewhat obviously, the position in time and space of the pitcher determines the position in time and space of the ball being delivered.

But that angle constrains how new pitches can be developed. Clayton Kershaw’s over-the-top delivery isn’t made to throw Max Scherzer’s slider. Max’s fairly classic three-quarters arm slot can’t throw Kershaw’s curveball. Pitchers have to iterate on what they already have in order to keep their release point consistent. If you’re beginning with one pitch, particularly a signature pitch, the menu of available secondary ones can be somewhat limited. And the longer you stay with that one pitch, the more limited your options—and chances for reinvention—might become.

So, welcome to the club, Wander Suero. Just know you might not be staying for long.

Come discuss one-pitch pitchers with me on Twitter at @sydrpfp.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now