Welcome to Ohtani Week: a celebration of, well, Shohei Ohtani. There’s been no player more fascinating or exhilarating since Ohtani graced our shores in 2018. Over time, the initial curiosity and excitement surrounding MLB’s first true two-way player in a century morphed into something more: Pure, uncut awe derived a superstar breaking barriers previously thought unreachable. All week, we’ll be talking about the most lovable—and possibly most talented—man in baseball. So throw on your Angels cap, grab your laptop charger, and dig in.

Since the moment the possibility first presented itself, one question has beguiled baseball fans above all others: What would it be like if Shohei Ohtani had to pitch to himself? The sport’s first two-way star in a century has single handedly spawned the most lurid topic for baseball fan fiction since the days of Fritz Peterson and Mike Kekich. So when we want to evoke the impossible, we do the same thing that Marvel movies do, and use computers. Specifically, we use the baseball simulation program of choice, Out of the Park 22.

Now, I know what you’re about to say: “Baseball simulations are so last year.” And I get that. This isn’t the newest ground we’re treading, but it’s okay: the great discoveries of science and the great works of art are all built through incrementalism, not miracle. We stand on the shoulders of giants. And we do it to envision and create a universe in which Shohei Ohtani is not the most special baseball player of our and our fathers’ generations. In fact, in the Ohtaniverse, Shohei Ohtani is not special at all. Because in the Ohtaniverse, there are 776 Shohei Ohtanis, all training their entire lives to destroy each other in baseball combat.

Why 776? Because it is the imperfections that give the emerald its luster, after all. So included with our Shohei clones are four mortals, there to provide the gods a yardstick. They are Nomar Mazara, Triston McKenzie, Tyler Wade, and Wade LeBlanc. I followed MLB’s lead and wiped out the entire minor league system, giving each team exactly 26 players to survive the year, and opened it up to a draft. Teams actually selected Mazara, McKenzie, and Wade; LeBlanc had to be manually inserted on his St. Louis Cardinals, erasing one Ohtani from existence.

Taking the reins of the Los Angeles Angels, I got a quick note from owner Arte Moreno (try to play .500 ball, try to sign Raisel Igelesias—a particularly strange request, given that he doesn’t exist in this timeline—and upgrade LF somehow). None of those ended up happening. Joe Maddon was back to manage, because I wasn’t interested in the minutia of team leadership. The clubhouse seemed like everyone was on the same page.

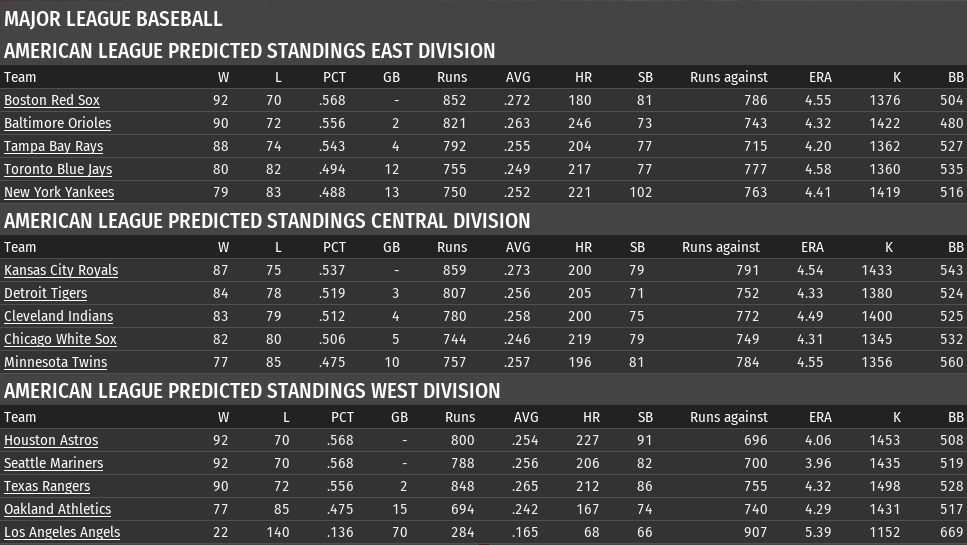

Those jerks who create preseason projections were not so optimistic.

It’s not paranoia if the media really does hate your team. Still, it’s strange that before one pitch, the fortunes of an army of clones could be projected so differently—all because of the fallibility of the scouts tasked with evaluating them. I couldn’t figure out what was going on—my lineups were set, my Ohtanis appeared to have just as much potential as anyone’s—but something apparently smelled rotten in the city of Anaheim. Never mind. I would prove them wrong. We would prove them wrong together, Shoheis and I.

On Opening Day, the Angels won 2-1 on the back of a sterling start by the original Shohei Ohtani, nicknamed “Adam,” who went seven innings of one-run ball. It was a fun day around the league; Ohtani enjoyed a five-hit day against the Cardinals, walked off the Astros with a two-out single in the 12th, and twirled a complete game against the Cubs. Best of all, however, was this delightful gift that OOTP gave us:

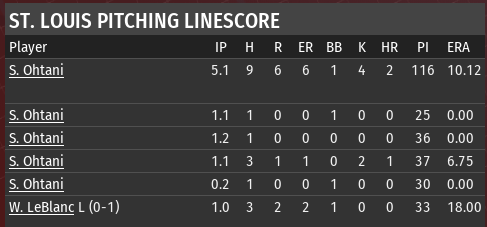

Opening Day, 25 Shohei Ohtanis with fresh arms ready to go, and with a one-run lead in the ninth, the Cardinals turn to… Wade LeBlanc. Who immediately biffs it. I love this game.

The Angels swept their first series, and I invited Joe Maddon into my office to talk strategy. We could only tweak so much, but I asked him to take advantage of the special circumstances surrounding the league. If there was one position that Ohtani might not excel at, for instance, it was catcher, so I asked the team to run more. And given that other managers around the league were working their starters for 110, 120 pitchers, I figured a 21-man bullpen would reward a quick hook. No sense in worrying about platoons with no lefties in the league, and Ohtani’s not susceptible to the shift, so we ignored those. With that talk complete, I figured the Angels were ready to defy expectations and make a run for the playoffs.

They certainly defied expectations.

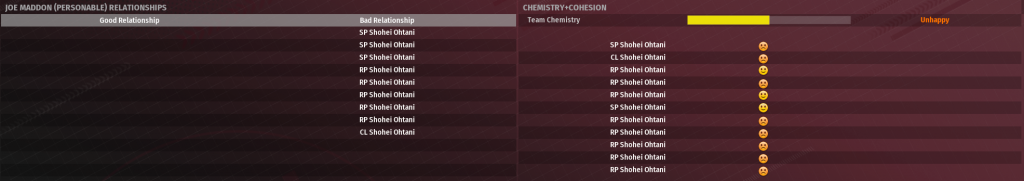

I switched from simming daily to weekly, but something about the Ohtaniverse broke Joe Maddon. The team lost seven straight. I stopped the auto-skip, simulated a few games manually, got the club back in the win column. But then, after a 13-13 start, the fast-forward button went back on, because life is finite, and the Angels fell back into their losing ways. The clubhouse grew tense.

The losing streak reached 10 games. Then 20. Things were getting bleak.

At this point I made my first act of divine intervention, going into the “Adam” Shohei and changing his leadership value from 93 to 153. After all, it was his rib from which baseball itself was created; no one could understand the troubles of his peers the way he did.

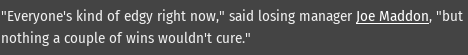

After 31 straight losses, Maddon sensed that perhaps his continued employment required justification:

The next day the Angels did indeed prevail, bringing their record to 14-45. “I’m glad we can make our fans happy with a win,” Ohtani told the Los Angeles News, in a sentence that is less likely to be true than any before uttered. The team lost 31 of their next 32 and crawled into the All-Star Break with a 15-76 record. By this point the clubhouse was well and truly lost; the atmosphere was “feuding,” and every player despised themselves and Joe Maddon in equal measure.

It was at this point that I discovered the problem: Maddon had, for the past three months, refused to set a lineup. If I asked him for one, the game simply didn’t respond. If I set one manually, he automatically erased it the next day. The result was that the starters weren’t getting rested, instead grinding until they got hurt, forcing a replacement to step in and slog until he too crumpled with fatigue. I fired Maddon on the spot and set myself as acting manager, setting an actual lineup out of the least broken Ohtanis, hoping to apply the modern technology of crop rotation to baseball.

Meanwhile, the rest of the league looked… like a normal league. Triston McKenzie started off with a 40.50 ERA in relief, but soon settled into an uninteresting 7.35 mark, laboring in middle relief for Colorado. Tyler Wade was the only other victim of overuse; being the league’s only natural infielder, he led the league in plate appearances well into the season, but soon wore down and fell apart. Nomar Mazara certainly played baseball. Shoheis were straining obliques and pitching shutouts and getting into fights. Every once in a while, one was lost for the year, but never so many on one team that it created a roster crunch. There were to be no Dee P. Gordons. As the year progressed they developed experience at their unnatural positions. Even a world full of perfection finds its own boring balance.

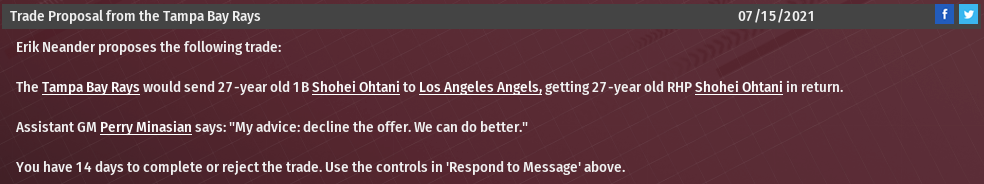

The rudderless Angels never found happiness, from a morale standpoint, but they did turn it around. Dipping to a Spider-like .158 win-percentage at their nadir, the team played 87-win ball the rest of the way, easily outpacing their preseason expectations and the 1962 Mets. Things did get exciting around the trade deadline:

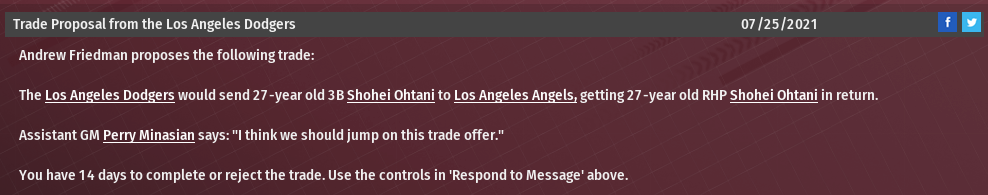

This offer was followed the next day by another:

Whatever else this particular Shohei had that the other one lacked, he certainly brought charisma. Upon committing to the second trade, the team reported that “our fans are ecstatic that you signed Shohei Ohtani. The overall fan interest is amazing!” The Angels did technically win the trade, as New Shohei posted a 105 OPS+ as the team’s primary third baseman.

Still, despite the turnaround, the Angels were eliminated from the playoffs with more than a month to go, and capped off the season in the worst possible way: By watching the Seattle Mariners, of all teams, clinch a postseason berth on their home field. (Don’t worry, the Mariners got bounced in the play-in game; OOTP is extremely realistic, no matter what the rosters are.) 26 Shohei Ohtanis were finally free of their personal Stanford Experiment, done losing and hating themselves. The common agreement was that they lacked a veteran presence, ironic given that their team was tied for oldest in the league.

One of the purposes of the experiment was to see what a full season of comprehensive greatness looked like, and the result was that it basically looked no different. Even in a league of clones, parity was nonexistent. The Athletics won 99 games, and the Padres lost 100. The unstoppable pitcher and immovable batter combined to produce a pedestrian .256/.326/.432 slash line, with an 8.5 percent walk rate, a 20.2 percent strikeout rate, and a 3.4 percent home run rate. Basically, cloning Shohei Ohtani 775 times had the effect of cloning the 2017 run environment once. Perhaps most disappointing: all those Ohtanis combined to steal 2,255 bases, even fewer than the real league managed in 2019. And they succeeded only 72 percent of the time.

Everything came down to what it always comes down to: The healthy teams won, the unhealthy teams lost. The rest was a wash. Baseball and modern economics can be awfully unsatisfying sometimes.

A breakdown of the best and worst Ohtanis in the Ohtaniverse:

| Ohtani | AVG | OBP | SLG | BB | K | HR | WAR |

| #36, ATL | .318 | .387 | .569 | 54 | 95 | 26 | 6.6 |

| #7, LAA | .124 | .186 | .175 | 24 | 174 | 3 | -4.6 |

| Ohtani | IP | K/9 | BB/9 | HR/9 | ERA | WHIP | WAR |

| #17, BAL | 198.1 | 7.3 | 2.3 | 1.13 | 3.72 | 1.22 | 3.9 |

| #8, ATL | 24.0 | 6.4 | 4.1 | 3.8 | 10.12 | 2.04 | -0.8 |

The original Ohtani, sadly, was chewed up and spat out by that villain, Joe Maddon, and despite never hitting the IL, never truly recovered:

| AVG | OBP | SLG | BB | K | HR | WAR |

| .161 | .213 | .244 | 19 | 136 | 6 | -2.7 |

| IP | K/9 | BB/9 | HR/9 | ERA | WHIP | WAR |

| 88.2 | 7.8 | 5.2 | 2.0 | 5.68 | 1.67 | -0.5 |

And the poor pathetic non-Ohtanis:

| Hitters | AVG | OBP | SLG | BB | K | HR | WAR |

| Tyler Wade | .183 | .221 | .231 | 17 | 155 | 3 | -1.6 |

| Nomar Mazara | .242 | .297 | .356 | 24 | 57 | 8 | -0.7 |

| Pitchers | IP | K/9 | BB/9 | HR/9 | ERA | WHIP | WAR |

| Wade LeBlanc | 21.1 | 4.2 | 2.9 | 4.2 | 7.48 | 1.62 | -1.1 |

| Tristan McKenzie | 48 | 8.2 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 7.12 | 1.58 | -0.5 |

There is something immensely comforting in knowing that in a universe of unfathomable probability, Nomar Mazara will just continue to be Nomar Mazara. That perhaps there is some nature in our creation, not just the capricious whims of nurture. That all universes are Mazaraverses, no matter which we happen to occupy. As the world crumbles and bakes around us, as all sense of permanence disintegrates like the desertified dust of our August lawns, Nomar Mazara will always be there to cast light upon the Shohei Ohtanis of our lives.

The Atlanta Braves won the Ohtani Series in six over Cleveland. Their second baseman, not their MVP center fielder, provided the heroics. The simulation has nothing to say beyond this point, which makes me glad, because it allows me to pretend that all 776 Ohtanis collected together, threw an enormous party, and dematerialized into pure light as their souls escaped and coalesced on the ethereal plane.

And then, next spring, the four remaining ballplayers in existence dutifully arrive to play out the 2022 season, knowing that they alone are cursed to remain in this terrestrial prison. Wade LeBlanc goes 20-142.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now