Welcome to Ohtani Week: a celebration of, well, Shohei Ohtani. There’s been no player more fascinating or exhilarating since Ohtani graced our shores in 2018. Over time, the initial curiosity and excitement surrounding the first true two-way player in a century morphed into something more: Pure, uncut awe derived from watching a superstar break barriers previously thought unreachable. All week, we’ll be talking about the most lovable—and possibly most talented—man in baseball. So throw on your Angels’ cap, grab your laptop charger, and dig in.

A small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum comprises the entirety of light visible to human beings. A few wavelengths beyond that in either direction exist colors beyond our comprehension. Shohei Ohtani lives at the very boundaries of our field of understanding. He slows himself down and descends from the ultraviolet realm for three hours each day so we can witness a fragment of his majesty. Our puny, underdeveloped brains could never perceive his true form. That’s just how science works (Co-author note: No, it’s not.).

No other person can do the things Ohtani does. His feats on a baseball field are well documented—even if we still can’t properly contextualize them—but he remains a superior being during the 21 hours per day he isn’t on TV. Here is a small, incomplete list of the things he does better than anyone else, on or off the diamond.

Questioning Fundamental Assumptions about Player Development

Even with the extinction of the LOOGY, hyperspecialization has become something of a norm. As Patrick Dubuque argued in discussing Mesopotamia, metalsmiths, and the DH, “Specialization is, at its root, a collective action problem: It creates results that no one wants, but that everyone has incentive to further along.” So, player development is often less toward the goal of being a baseball player, and more toward the goal of being a particular specialist within “baseball players” as a class of professions.

To put it in biological terms, we have narrowly characterized ecological niches, and with the exception of some generalists like a handful of super-utility players, we have a game of specialists to fit those. The thing about being a specialist, though, is that ecosystems change.

When the baseball ecosystem changes, being able to do more is of greater value than being able to do few things excellently. In Ohtani’s case, he hasn’t exactly made that trade-off. But traditional player development tends to funnel players relatively early, and with a few Ankielian exceptions, once you’re either a pitcher or position player, that tends to be your path. There are both historical and practical reasons for this, but it’s always good to have a check on some of the fundamental assumptions we’re making about the sport. In this case, looking up long enough to go, “Well, why not both?”

Whatever This Game Is

Here is a game of some kind at which Shohei Ohtani is the greatest ever, because of course he is.

The thing about baseballs is that they tend to roll on concrete. (More science!) Tossing and spinning one just right so that it bounces on a step, then stops on said step, is a feat only a demigod can accomplish. It’s tantamount to stopping a moving freight train or flying faster than the speed of light. Don’t believe it? Go try it yourself and see how quickly you get frustrated (the baseball thing, that is—please don’t stand in front of trains or leap from tall buildings).

Discerning viewers will notice that Ippei Mizuhara, Ohtani’s translator, appeared to have a successful toss at the end of the clip. This is because Shohei broke the system. It would have been impossible just seconds earlier. Even on our best days, average schmoes like us can only follow in his footsteps, striving to recreate his accomplishments. Such is the pinnacle of human existence. With apologies to Mizuhara, it’s all downhill for him from here on.

Hugs Above Replacement

The analytics team at Baseball Prospectus is proud to introduce a new metric—Hugs Above Replacement. We have provided a detailed description of 80-grade hug mechanisms for your reference.

First, the load/gather, with the load as a movement with the upper body (usually the hands and arms) during the loading and striding phase of a hug. A proper load occurs with the hands and stride working in complementary fashion to provide both expansion and depth to the hug interaction. Some hugs may also involve more elaborate load gathering, such as strides, jumps, or post-Gatorade head-rubs. Like other aspects of the hug, load represents a timing mechanism that can be helpful or a roadblock to success.

Other metrics to consider:

- Body control: How well does the hugger square the hug target?

- The preparatory arm-wrap: To what degree does the hugger gather and retain the hugee? This can cause the hug to have length.

- Balance: Does the hugger jump, bounce off their front foot, flail, or do anything that causes them to lose control of hug fluidity?

- Timing/Rhythm: Is the hug at an opportune and deserved moment? Does the hug contain other components that can lengthen its duration? Does anyone fall over?

- Raw power: How well does the hug communicate comradery and team cohesion? Does it result in amplification on social media? Are there gifs?

Lastly, a few common descriptors used in hug scouting:

- Power Type: Oppo (for members of other teams or extreme height differences); up the middle (for hugs following no-hitters); loud sound (mostly, yelling); lift approach (when someone is gathered off their feet); clutch (clutch hitting may have fallen out of favor as a stat, but clutch hugging remains a powerful indicator of future hug success).

- Approach: Low/high chase rate (Is the hugger often denied hugs?); aggressive/passive (Does the hugee merely accept the hug or do they actively engage with it?); quiet/hard takes (Is the hug stoic? Emotional? Are they crying? Are you?).

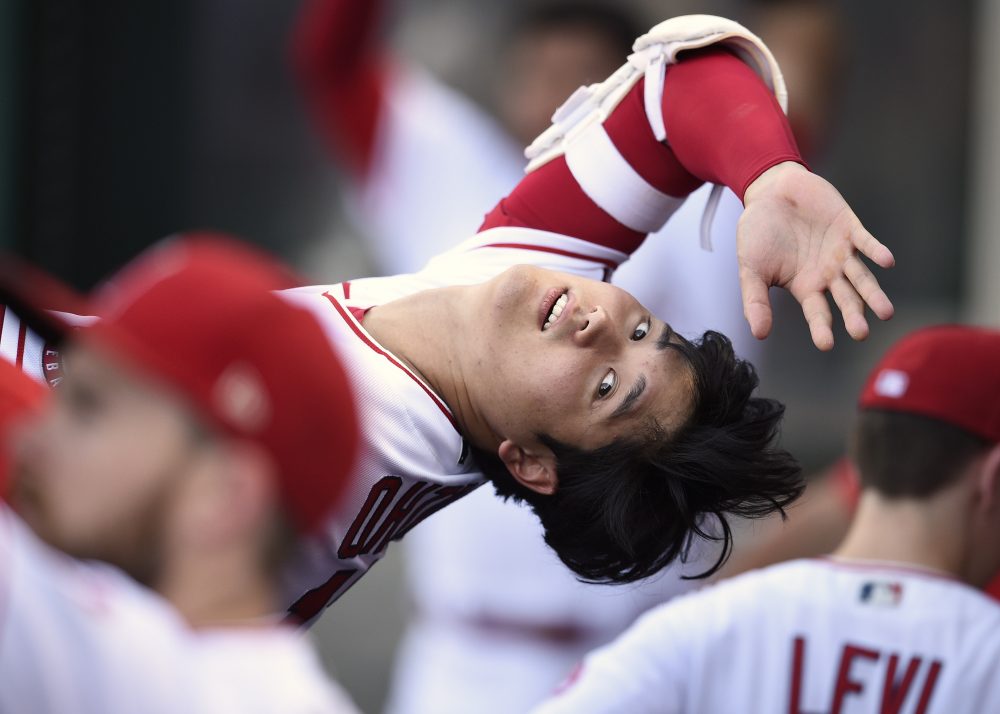

Here we have an 80-grade hug. Note the refined mechanics and powerful downward action, as well as the added touch of clenched fists. It’s a deceptively simple approach in the dugout to which other players should aspire.

Breaking the System

The good folks at Baseball-Reference almost always post box scores in the early morning for the prior day’s games. The 2021 All-Star Game took much longer than usual. It was Ohtani’s fault:

At last week’s All-Star Game, he started at two distinct positions simultaneously (pitcher and DH). When he exited as a pitcher after the first inning, he stayed in to take a second plate appearance in the third. This bucked baseball’s “no re-entry” tenet consecrated in the days of Alexander Cartwright. The digital pages of B-Ref contain a vast wealth of knowledge and history, yet he still made them rewrite their coding.

Ever since he became a professional, he’s shattered the structure of the sport. The processes by which players enter affiliated baseball are sacred to MLB. For U.S. and Canadian players, there have been amateur drafts every year since 1965. International amateurs must abide by carefully hewn signing rules and restrictions chiseled out in collective bargaining. International professionals from Japan and South Korea must be posted by their team if they wish to jump to MLB before they become free agents. One of the purposes of these systems is to limit options for players as much as possible.

Ohtani, a being of a higher authority, nearly caused these systems to collapse on multiple occasions. Upon graduating high school in 2012, he nearly went directly to MLB. This was practically taboo in Japan; no Japanese player has ever skipped straight from high school to the American minor leagues. The Hokkaido Nippon-Ham Fighters drafted him first overall anyway, then convinced him to stay home by promising him the chance to hit as well as pitch, whereas MLB clubs would’ve taken the bat out of his hands.

Five years later, he made the decision to jump to MLB as an established two-way star. Since he was still only 23 years old, the most uniquely talented baseball player in the world was still subject to MLB’s draconian international amateur spending restrictions. His contractual value in an open market would have easily exceeded $200 million and the Angels’ posting fee to the Fighters was $20 million, yet he was forced to sign for just a $2.3 million bonus and the MLB minimum salary.

The upshot was a free agent courted by all 30 MLB franchises who couldn’t be wooed by money. No one had any clue where he might sign. Here’s one article predicting five landing spots, none of which were the Angels. Every outlet ran similar articles, and almost nobody got it right. For better or worse, it was a total upheaval of traditional free agency.

Even now, he’s bending and breaking rules. Manager Joe Maddon has eschewed the DH multiple times this season. In theory, that’s a major competitive disadvantage, but, well, it’s him. Ohtani plays his own game and we love him that much more for it.

Splitting

Ohtani’s splitter is one of the best pitches thrown by any pitcher in the world. Opposing batters hit .080 against it with a .127 wOBA, 54.7 percent whiff rate, and 60.5 percent strikeout rate. Those numbers are all the best in MLB for any splitter thrown by a starting pitcher this season.

The world’s greatest splitter isn’t limited to pitching. Lots of things can be split! The CERN Large Hadron Collider splits atoms with a machine based on his splitty. (Even more science!) Have you ever tried to split a log using an axe? Shohei doesn’t need one. If you enjoy split pea soup, send your gratitude to Ohtani. How do you think all those peas got split in the first place? You can send your thank you notes to his offseason residence in Split, Croatia. Here are 30 cool-looking objects split in half. Here’s the process that split them:

Bringing People Into the Sport

Ask any non-baseball fan, such as the commissioner, and they’ll tell you the fundamental things wrong with baseball. It’s slow. It’s boring. Its stars have the charismatic appeal of cold oatmeal. To be clear, none of these are actual issues with little-b baseball, as a game, which is just about the best way to spend a day in summer. But many of them are perceived issues with the modern incarnation of capital-B Baseball as it appears on national broadcasts.

Shohei is in no way the game’s only crossover star. There are plenty of exciting, charismatic, personality-having players—and plenty of scandals, resentments, and petty squabbles that fuel narratives and fannishness. Appreciating some finer aspects of baseball does tend to require some fluency in metrics, though less than baseball’s detractors would like to claim.

But appreciating Shohei doesn’t. His success is remarkably simple to communicate: He pitches and hits, and when he hits, he hits a lot of home runs. There’s a neatness to that, an economy of language that translates well into YouTube dinger highlights.

Or to quote Marcus Semien’s son’s reaction to Semien’s first All-Star selection (as recounted by the Yankees radio broadcast on July 3rd): “You get to play with Ohtani!!”

There, easy. Now put him on the side of every cereal box.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now