Two weeks ago, newly hired New York Mets general manager Jared Porter was revealed to have sexually harassed a female reporter. Our editorial covering the incident included this passage:

Porter will be fired but the system, the culture within Major League Baseball, will be found innocent for the nth straight time. This is information of which some people have been aware for four years, and there’s little reason to think it more likely the next incident isn’t buried for four years. Or, to be more realistic, that the “next” incident hasn’t already been buried for two.

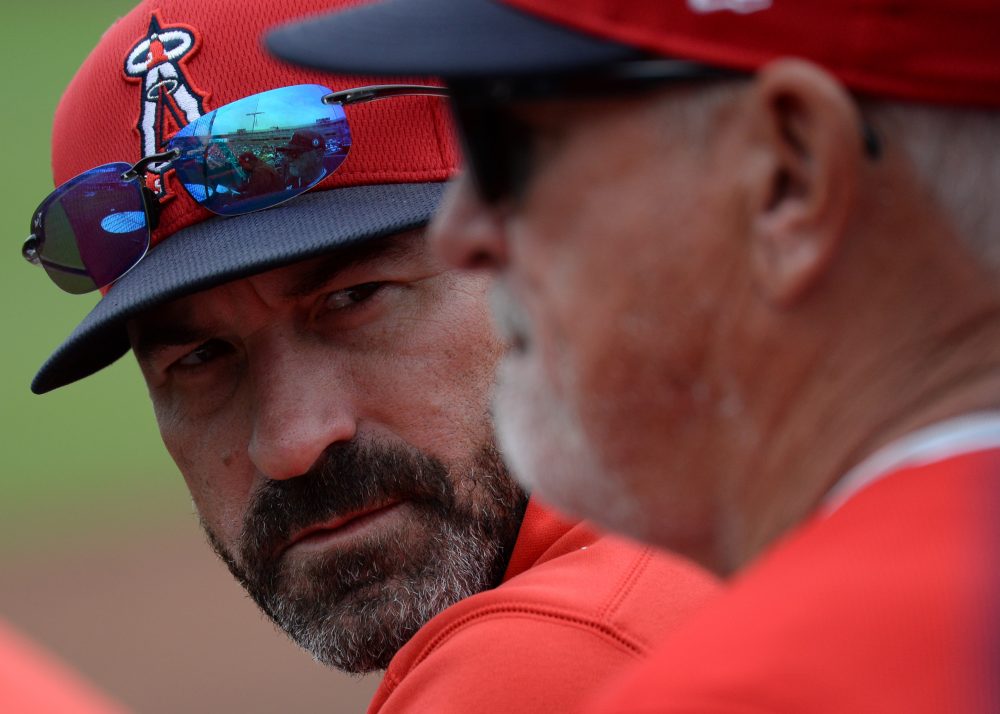

Two and a half years ago, as reported Monday evening by Brittany Ghiroli and Katie Strang at The Athletic, Mickey Callaway instigated one of his multiple pursuits of women within sports media, pressuring her into extracurricular contact, sending multiple unreciprocated messages and date requests, asking for nude pictures. Her story was one shared by four other women revealing a pattern of abusive behavior, spanning three organizations: Cleveland, New York, and Los Angeles.

Callaway’s fate is in transit as this article goes to press, late Monday evening, though given the prompt disposal of Porter it’s fairly safe to assume. Equally reliable will be the reaction of those who evaluate the evidence and conclude that justice has been served. A man did something wrong, and gets punished for it. Personal responsibility wins again. That’s how things are supposed to work, right? Just as it did last time, just as it will next time, ad infinitum, a justice continually dispensed, continually ineffective.

***

When something happens with consistency and regularity, it becomes a pattern. When that pattern is exerted relentlessly on a particular group, it becomes an expectation. This is not inherently a bad thing. It’s a rough sketch of how trust is formed, the basis of the rapport that reporters are expected to build with players, coaches, and executives. The ability to learn the rules of that interplay is one of the most critical if invisible tasks in which a reporter engages. When information is key, privacy is a rule, secrecy a given. Essentially, this is true of any relationship, any in-group—if someone cannot trust you to keep to yourself information they do not want with others, why would they voice it?

There’s a critical corollary to this system (and let’s be clear, it is a system), however: Both parties are supposed to be able to walk away. It’s the recourse you are meant to have when someone is being disrespectful, unkind, or otherwise breaking trust. It has immemorially been and remains a fundamental flaw in human society, though, that relationships are so often inequitable. A person can’t leave their shitty relationship because their partner controls the finances. The inappropriate professor has pull over the futures of their students. A worker cannot leave a job in which a boss puts them in harm’s way because they have no other way to pay their landlord. As Yahoo Sports’ Hannah Keyser pointed out, this certainly is a foundational societal issue—but it doesn’t mean it’s any less of one, striking and grating, in Major League Baseball.

It’s not that those who hold and exert power imbalances for their own ends don’t know what they’re doing. Quite the opposite, rather—these people are typically drawing on and reaffirming the playbook of abuse, aware that their power insulates them from consequences. This is, basically, an outline of the formation and maintenance of a system of oppression. Not to say that amiable, mutually rewarding relationships with uneven power dynamics cannot exist, but that their existence is predicated on the unwavering comporture of the person with superior influence. When that responsibility is eschewed, the person whose dignity is being violated is far too often presented with a choice between important resources to one’s livelihood or personhood and a damaging, potentially deleterious relationship. Aware of this, the person breaking trust and boundaries often chooses to offer incentives to maintain the relationship. It’s a poison apple, and an abuser often goes out of their way to clear out the rest of the bunch. It happens all the time, to be sure, a stark reality made all the more dismaying. It happens everywhere, but it happens here too.

Mickey Callaway has been a coach in one of three MLB franchises for 11 years, since 2013 as one of the three most influential uniformed coaches in each of those organizations. It comes as no surprise that his pattern of harassment was, as the reporting of Ghiroli and Strang reveals, “the worst kept secret in sports.” The article describes the harassment, in person and via text, Facebook, and LinkedIn, of five women, notes that seven women relayed having been warned about the sort of behavior as Callaway yo-yoed around the country. The existence of a network for women to support each other and ward one another away from potential abuse is unsurprising in the context of an overarching system that makes no sincere provisions for its prevention. When there is no broad accountability, it will be back-channeled and makeshifted as the only form of protection available. The heartening nature of that mutual support is contrasted with the dismaying reality of why it is so deeply necessary.

In Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida, often labeled a problem play (difficult to fit into a genre) in part because of its handling of sexual coercion, Odysseus gives an impassioned monologue concerning the importance of the ordered universe:

The heavens themselves, the planets and this centre

Observe degree, priority and place,

Insisture, course, proportion, season, form,

Office and custom, in all line of order;

… when the planets

In evil mixture to disorder wander,

What plagues and what portents! what mutiny! …

Take but degree away, untune that string,

And, hark, what discord follows!

There is a society-long impulse toward maintaining the status quo, not only because this is how things are done, but because to upset the extant hierarchy is understood as risky. To an extent it’s true—establishing a system where accountability is more than a word poses a risk to all those who have reason to fear its tendrils. One factor enabling actors such as Callaway to act in this fashion unabated for a decade-plus is their assumption that those they victimize will observe their degree, priority, and place—because they are often in positions where they see few other options. That same insularity enables those who hired or oversaw people such as Callaway to dodge responsibility for what happened in their tenure as outside of their sphere. The system doesn’t work for those of lesser priority because it’s not intended to—it’s just that, as opposed to the early modern period, we’ve come to see that design as a bad thing. Fashioning accountability is a clear threat to the system MLB has in place—and it should be, because the present system is already quite literally deracinating, displacing; recall the reporter harassed by Jared Porter left not only the industry but the country.

***

Mets president Sandy Alderson, in three weeks connected to two former employees engaging in pervasive harassment, said the only thing he would ever be expected to say: He was unaware, and the team will be altering its hiring procedures to ensure there is no future recurrence. The question of how he was unaware when so many were goes unanswered along with that of it not being his basic responsibility to be aware of such matters. They won’t be answered, can’t, because to do so would require either an admittance of cognizance on Alderson’s part or an admittance of an endemic failure of such in an avenue that is clearly within the purview of his job. If it can be answered, to put it another way, someone will eventually demand it should. Or, to be more blunt, it could be a lie.

One main reason behavior such as Callaway’s or Porter’s is eventually able to come to light is the persistence of messages, especially for reporters, in the digital age. Women who are on the receiving end of harassment—and as is said by countless such people whenever a similar situation is revealed, that group includes most women—have the ability to hold onto evidence of their harassment until they are sufficiently insulated from the retribution those with greater power can so easily exert. That such a failsafe exists is little salve, however, when it ultimately means that these women are not only alone in protecting themselves but feel insufficient security to report the abuse immediately, well aware that the consequences to their future livelihood could be more significant than those incurred by the perpetrator. Callaway has made more money in the last decade-plus than some reporters might make across the course of their careers. It seems as improbable to think he was not aware his actions would eventually come to light as to think he was unaware of their rank unacceptability. He didn’t care because he didn’t have to. What it comes down to is that someone has to care, or be made to.

Major League Baseball was not aware. Alderson was not aware, though someone within the Mets organization was aware in 2018. New Mets owner Steve Cohen assures the actions would “never be tolerated” under his ownership. You see a lot of actions in MLB that would never be tolerated, except that people are forced to tolerate them every day.

The idea of a meritocratic system is that there are supposed to be consequences that are meted out sensibly, opportunities feted to those who are deserving and capable. This abuse of power and of people has long been happening, with the only real distinction of the modern age being that technology enables evidence to endure. So long as a system in which self-evident abuse is tolerated again and again by MLB’s constituent organizations persists, as long as accountability is left to the ether, it’s difficult to see progress for women within the sport as anything but chipping away at an iceberg. Even if it’s moving, you’ll never notice it within your lifetime.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now