Sunlight and shadows vividly adorned the Busch Stadium field before the start of Game 2 of the National League Championship Series. The outfield and most of the infield were drenched in blinding sunshine for the 3:08 PM game. But with the sun descending over the horizon, the ballpark’s grandstands and lighting banks overhead cast dark shadows down onto the batter. The contrast between lightness and darkness prompted immediate discussion by the TBS announcing crew.

“You could already see the effects of the shadows creeping out over home plate,” play-by-play announcer Brian Anderson said as the first pitch was being thrown. “That’s going to be a story here, as you heard Curtis Granderson mention in the pre-game show.”

Both the Nationals and Cardinals starters mowed through the opposing lineups as the shadows and bright light shifted throughout the first three innings. Max Scherzer struck out six and didn’t allow a hit through the third, while Adam Wainwright struck out three and surrendered a Michael A. Taylor homer for the only run. The starters’ success lent credence to the assertion continually made by the broadcasters: that batters have a difficult time judging pitches when the path between the mound and plate is obscured by shadows, leading to less offense.

“It’s always something that hitters talk about, discuss, when you get into the postseason,” Anderson said when Juan Soto batted in the fourth inning. “Every now and then there’s the late afternoon starts in the regular season, but it’s more consistent in the postseason.”

Late-afternoon games are frequently built into the postseason schedule as Major League Baseball spaces out play to minimize overlap. It’s why the 2019 playoffs have brought the return of the annual playoff narrative that shadows adversely affect hitters. The reasoning looks plainly obvious when batters take noncompetitive hacks and allow middle-middle strikes to pass by untouched. But these effects are presented to viewers as certainties when there isn’t hard evidence of a penalty on hitters’ ball-tracking ability.

This analysis will test the shadows theory. First, we’ll evaluate whether time played a role in creating strikeouts and walks at open-air ballparks in 2019. These time recordings are a product of MLBAM’s Statcast system, which stamps each event. We don’t know exactly what batters are seeing from moment to moment, but the time is a worthy proxy for the visual conditions the sun imposes on the field.

Time was modeled along with several controlling factors that can affect batter success. Batter and pitcher talent were factored into the models with pre-season PECOTA strikeout and walk projections. The model also accounted for handedness, pitcher role (starter/reliever), and conditions in each plate appearance: park identifier, inning, inning side (top/bottom), and the pitcher’s times through the order to that point.

These variables were flowed into a pair of generalized boosted regression models (GBM): one of which predicts whether plate appearances end in a strikeout, and the other assessing the likelihood of a walk. The GBM is a good candidate for this exploratory analysis because it fits decision trees many times over to fix areas of underperformance, permitting non-linear relationships and interaction effects along the way. The models also produce partial-dependence plots showing the relationship between each variable and strikeout/walk probability, holding the other factors constant.

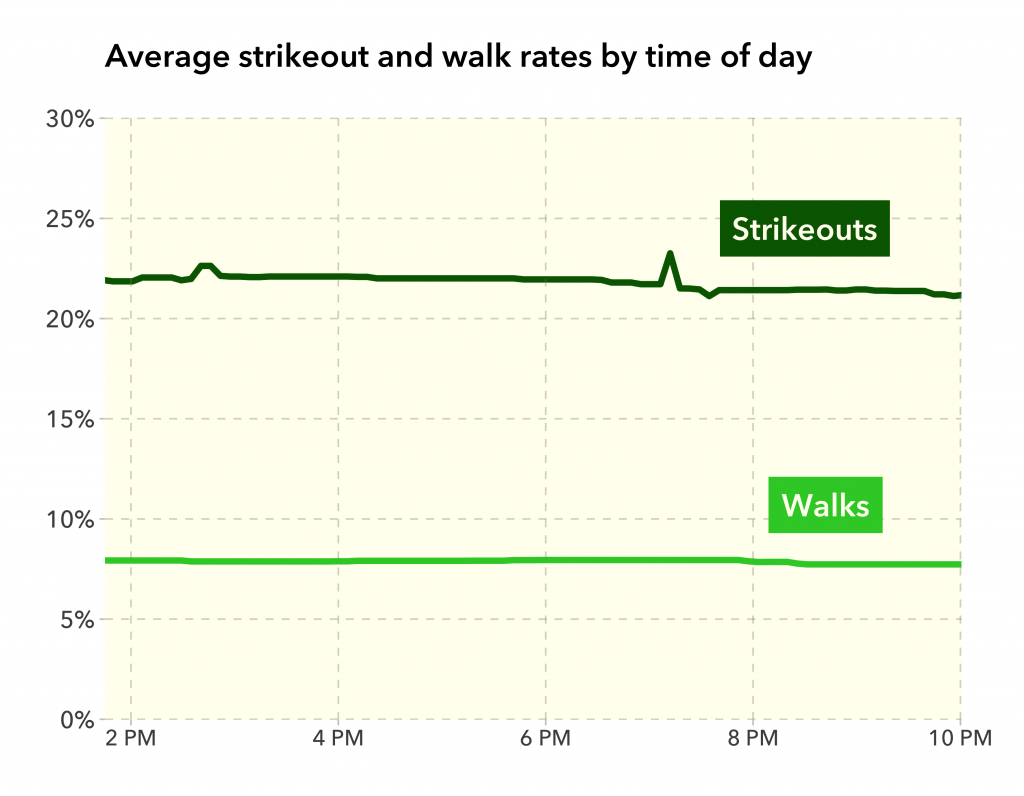

Anyone dreaming on the effects of shadows should expect strikeouts to spike and walks to plummet in the late afternoon. But they’d probably come away disappointed with the results in the partial-dependence plots.

Strikeout and walk rates are almost entirely flat all through the day, from the early afternoon through the late evenings. In fact, the curves closely hug the league of averages of strikeouts (22.4 percent) and walks (8.3 percent) present in the training data. Outside of a few quick blips in the strikeout trend, there’s nothing here to suggest hitters struggle as the sun sets in the late afternoon. Even though this model doesn’t identify the intensity of the sun or cloud cover overhead, changes in strikeout and walk rates should have emerged in the chart if resounding effects were real.

The book on possible shadow effects doesn’t need to be closed just yet. The analysis can be expanded by introducing a new pair of models that account for the sun’s position. By merging the date and time of each plate appearance with ballpark latitude and longitude, the suncalc package in R can spit out the sun’s angle above the horizon (altitude) and angle along the horizon (azimuth). Additionally, park orientation was introduced in the new models to add specificity.

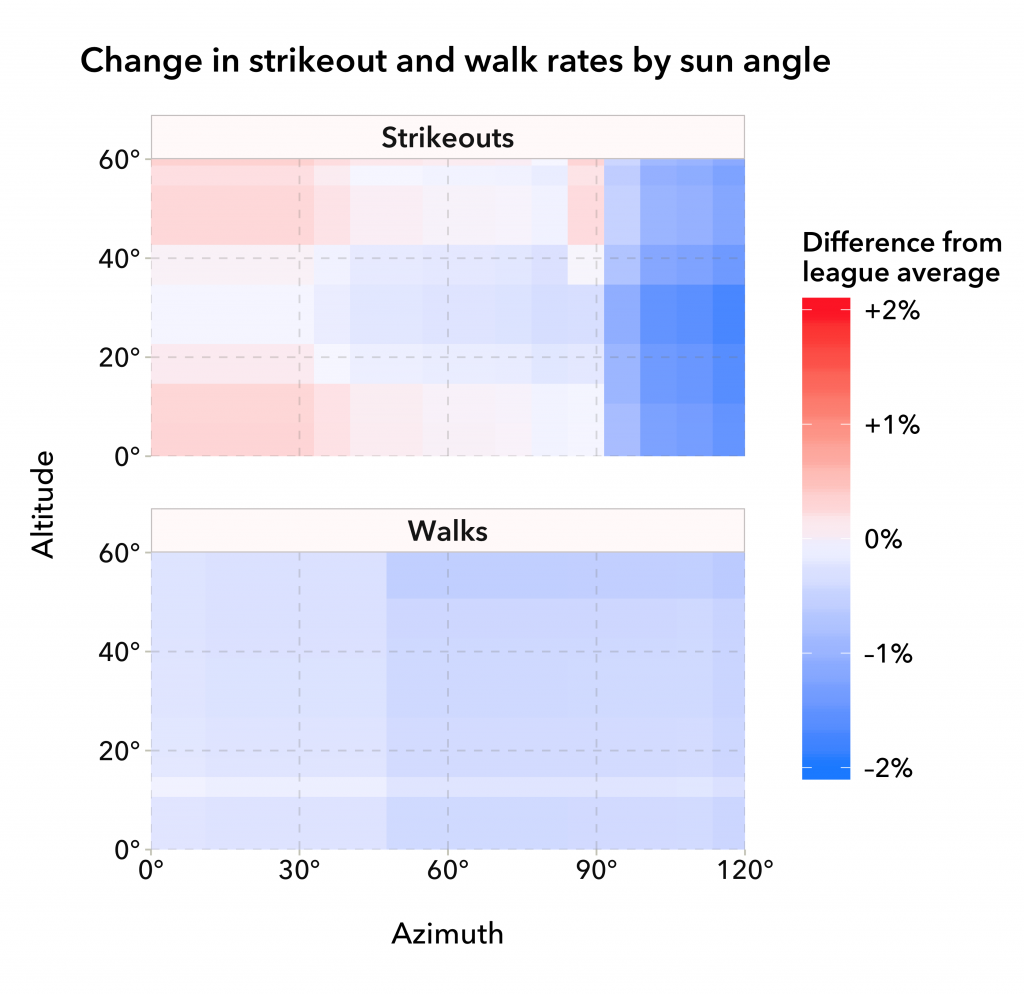

Below is the partial-dependence plot showing how strikeout and walk rates change as altitude and azimuth vary in afternoon hours. Note that azimuth, as measured here, is the angular distance along the horizon measured clockwise from due south (0 degrees).

First, notice the gradient along the right side; its range is small (going from +2 percent to –2 percent), and its upper reaches are ultimately not even needed. In no degree combination do strikeouts and walks surge by as much as 0.5 percent. The model traces a very small increase in strikeouts at an azimuth between 0 and 33 degrees, at a pair of high- and low-altitude ranges. But the rise in strikeout rate is only around 0.3%, which isn’t a noticeable change. It means that for every 333 plate appearances taking place at these sun positions, we could expect one additional strikeout. Moreover, these altitude/angle combinations often won’t push shadows across the field; the typical plate appearance with the sun at a 0–30-degree azimuth occurs at the early-afternoon time of 2:15 PM.

Only when the azimuth is at least 90 degrees past due south—typically around 8 PM—do we start to see some change in the strikeout chart. But it’s a decrease instead of the big upswing we’ve been waiting for. And down below, the walks chart is consistent in showing a faint decrease in walks. It doesn’t vary with the sun position, which splashes more cold water on the shadows theory. So even when the sun’s position is factored into the equation, it’s clear that pronounced effects of shadows on ball-tracking ability aren’t present in the data.

***

If the shadows didn’t fuel the starters’ success on Saturday, the real reasoning is obvious: it’s because these pitchers are good. Scherzer ranked among baseball’s top five pitchers in DRA- and strikeout rate in the regular season and continued his Hall-of-Fame-quality pitching in his age-34 season. Even after the shadows fully stretched from the batter box to the pitcher’s mound in the fifth inning of NLCS Game 2, Scherzer continued to dominate and didn’t allow a hit until the seventh. Wainwright also fared well after being fully surrounded by shadow, striking out five hitters in his next three frames. While the former Cardinals ace is a diminished pitcher, the 37-year-old still turned in an above-average 2019 campaign and fit the steely veteran archetype this October.

More quality pitching is on the agenda for the afternoon games to come. American League Cy Young Award frontrunner Gerrit Cole will launch his laser beams from the Yankee Stadium mound in today’s 4:08 PM game. He’ll be opposed by uber-talented (and finally healthy) Yankees starter Luis Severino. On the National League side, a Cardinals win tonight would put a 4:08 PM Game 5 onto the schedule in Washington tomorrow. That tilt would likely bring Anibal Sanchez and Miles Mikolas back for a rematch after the two above-average pitchers turned in strong performances in shadow-free NLCS Game 1, which began at 7:08 PM in St. Louis.

Beyond the pitching talent seen throughout the playoffs, offensive outages plaguing ballparks this October can also be attributed to a compositional change in the baseballs. Analysis from BP’s Rob Arthur shows that the playoff balls have much higher air resistance, causing many long flies to die out on the warning track before clearing the fence. With hitters gearing to launch but making contact with a baseball seemingly out of a different era, they’re suddenly not meeting the homer-happy standards part and parcel to the modern game.

The purported effects of the shadows lack the same tangible proof. The long-discussed shadows topic appears to be a myth, one of many that abound in the playoffs and act as explanations for disappointing losses. So if Cole and Severino dominate the ALCS lineups today, expect it to be because of their elite stuff—not some vague ability to manipulate sunlight and shade with their pitches.

Thanks to Harry Pavlidis and Martin Alonso for supplying the data used in this piece.

Thanks to Dr. David Kagan for his assistance in regards to stadium orientation.

Appendix: Model Details

For the technically inclined, here are some details on my models. The GBMs were trained on 66,491 randomly-sorted plate appearances from this season in open-air ballparks, with domed and retractable-roof stadiums entirely left out. Thirty-six versions of each of the four different models were trained with varying interaction depth, number of minimum observations per terminal node, and amount of data used in each iteration. Brier scores were produced on each of these models through a separate test data set of 44,242 observations.

The models with the lowest Brier scores were selected, but all performed similarly. The final strikeout models had Brier scores of 0.170, while the final walk models produced less error with Brier scores of 0.076.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now