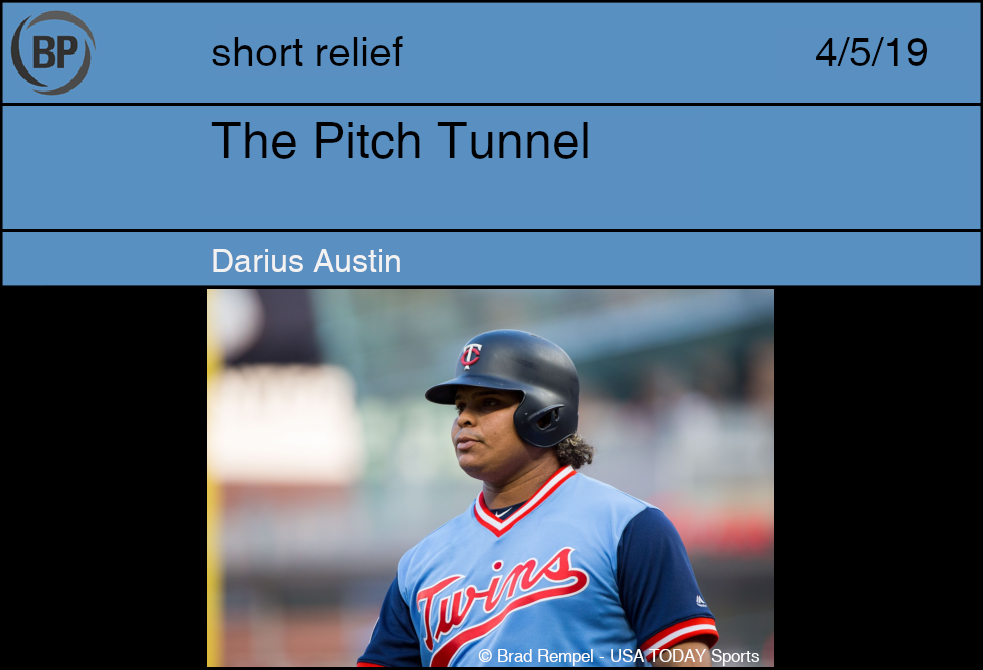

Willians Astudillo stares out at the mound. Many would say he is waiting for the pitch, but that’s not really true. It implies some agency on the part of the pitch. Now the pitch waits for Willians Astudillo.

Almost three months have passed since Astudillo last struck out. It was a bad call, a pitch at least a couple of inches below the strike zone and a little outside. A close call, perhaps, but Astudillo didn’t swing at it, and everyone knows what that means. That umpire isn’t in the major leagues any more.

Astudillo would have broken DiMaggio‘s record too, if not for the fact that teams had walked him in every plate appearance on more than one occasion. No matter; such things are no longer important. People keep asking him about if he can become the first player to hit .400 since Ted Williams, or whether the Twins will win the World Series. Fortunately, they assume his surprisingly controlled replies are humility and not disinterest.

At first he just thought that the feeling was being ‘in the zone’. He’d heard plenty of athletes talk about it. He always knew when he could hit a pitch and when to let it go. Once he was in the majors, he realized that it was something more, that he possessed something no one else had. Maybe he’d always known that wasn’t just ‘the zone’. There was something untapped, lurking in the recesses of his mind, that he had not yet reached.

He was getting close, though. Each day, the ball seems to slow a little bit more. The seams are clearer, the spin is easier to pick up, whether to swing is barely a decision.

So Astudillo stares at the ball in the pitcher’s hand. The bases are loaded – he thinks – and the scores are tied; it is unimportant beyond the fact that they believe they have to pitch to him. If they knew they would never pitch to him, but no-one knows.

The pitcher finally releases the ball to meet its fate. A curveball? The type of pitch no longer matters. Astudillo concentrates on the ball, only the ball, arcing inexorably across his field of vision and spinning slower and slower, until it’s not clear that it is spinning at all.

It isn’t spinning at all.

For several moments, he does nothing. Keeping his eyes on the ball, he’s only vaguely aware that nothing is moving around him. Astudillo lays down the bat. He can see the path of the pitch, not just the path it has taken but the path it will travel. There is a disturbance, a column, a tunnel of its past and future existence. A tunnel that ends at the plate, where it would have been met, as always, by Astudillo’s bat.

Astudillo moves round to the end of the tunnel, crouching so he can see inside. There is a shimmering in the air, like a waterfall had appeared in front of the mound. He reaches out and with one finger, breaks the surface. All becomes clear.

Can it be a slump in the first week, or is that just your limp life?

I hate pressure to act surprised by bad performances.

Let that sink in, that’s what they say when they use a number.

Smash on through with it then, show us who’s boss.

If a stagger step can be planned, could that lurch be productive?

Picking all the knits you wouldn’t pretend you’d snagged on purpose.

You can’t trip over nothing and say “I meant to do that.”

People know that’s a lie. And they have a terrific memory.

How many steps in a typical dance move, moves in a routine?

I’m saying you can go ahead and say it. The plan was otherwise.

The talk turns to makeup and lights and the traffic thins out.

Our host apologizes, explains she’s still practicing her stops.

It’s been a long day. Strike one this, ball one that. Out, safe, dust the plate. People yelling, him yelling louder back. It’s not what I imagined doing when I grew up watching the sport, Ron Kulpa thinks to himself. But it’s what I’m doing now. As he is about to rest his head on this questionable hotel pillow for the night, he knows that he can’t really do whatever he wants, but he needs everyone around him to know that. If he can’t escape the fallout from his authoritative tirade against A.J. Hinch, then he knows that he might be out of a job. It would be nice to just be able to literally do whatever he wants, even if it was for a day.

Kulpa wakes up the next morning none the wiser, moseys down to the continental breakfast. He sees the giant tray of eggs. They weren’t that good the day before. Better stay away from them. He just goes with his usual breakfast of a blueberry muffin, a yogurt with granola and 12 cups of coffee. Back up to his room, he realizes he doesn’t have his keycard. Again! He just wants to get back in the room and use the restroom. He tries his luck with the handle, and for whatever reason it opens with ease. Was it … broken? Never mind, he’ll worry about it after the emergency pit stop.

More hints emerged throughout the day. He didn’t want to wait in line for a sandwich so everyone just got out of the way for him, inexplicably. He didn’t want to pay cab fare to the stadium, so the driver let him. I really am doing whatever I want, Kulpa realized, several hours before most others would have. And of all nights, it’s not my turn to call the game from home. This one only took a few minutes before he realized he absolutely could.

He didn’t exactly get a good night’s sleep, so he didn’t quite feel like squatting for most of the game. So he pulled a lawn chair behind home plate and sat between pitches. By the third inning, he felt he was calling balls and strikes immaculately. No pitches were called incorrectly. So he simply took a nap. Anytime he heard the pop of the catcher’s mitt, he just said whichever call came across his head. For a while he alternated. Then he did seven balls in a row, for funsies. For the entire sixth inning he went with an alternating Fibonacci sequence. Meanwhile he had also ejected both managers, several assistant coaches, 60 percent of the players and the entire right field bleachers.

The game was still tied, mostly because the pitchers were simply tossing the ball six feet wide just to see what would happen. Boos intensified. Players couldn’t take it anymore. But Kulpa wasn’t such a fan of this. He suddenly stood up, with dark clouds gathering over his head. With one swift pump of his arm, he decided to eject everyone. And several minutes later, it was just him and this ballpark, lights on, the world at his fingertips. He could now do anything he wanted. But he realized, several hours into his leisurely sit, that there was no other authority to enforce. No more insubordination to quash. There was nothing left to do. Also all the doors had been locked, and his elementary school teachers started parachuting from helicopters with all the pop quizzes he had failed when he was a small boy.

Then Kulpa suddenly woke up in a cold sweat in his hotel room. He’s never having those eggs again.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now