You are about to enter another dimension, a dimension not only of sight and sound but of mind. A journey into a wondrous land of imagination. Next stop, Twilight Zone Baseball.

Submitted for your approval: The worst team ever assembled. A team so remarkably inept that history wouldn’t allow them to be forgotten. A team that compiled a record of 20-134. A team that lost 40 of their last 41 games. I’m speaking, of course, about the 1899 Cleveland Spiders. Still not sinking in? Try this one on for size: The 1899 Cleveland Spiders were so bad that there would be no 1900 Cleveland Spiders. Following the team’s 10-1 loss on Opening Day, The Plain Dealer posted a headline reading “THE FARCE HAS BEGUN.” They were not wrong.

But where most men saw ineptitude, another sought opportunity.

Meet Eddie Kolb, 18. Like many of us growing up in our backyards, Kolb had dreams of one day making it to the big leagues. By 1899, Kolb was captain of the Norwood Base Ball Club, an amateur team in Ohio, but had still yet to appear in a single professional game in his life. Despite his insistence, it appeared as if Kolb’s baseball dreams would go by the wayside, as most of ours eventually do.

That didn’t stop good ol’ Eddie, though. You see, Kolb was also working as a cigar boy at the Gibson House, a Cincinnati hotel that was often frequented by, you guessed it, the Cleveland Spiders. Over the course of Cleveland’s terrible, horrible, no good, very bad season, Kolb befriended the club’s player/manager Joe Quinn (who was sadly one of the team’s better hitters, batting .286/.312/.345 at age 36). So when it came time for the Spiders’ last series of the season, Kolb had a proposition ready: Let me pitch in the team’s final game, and I’ll give you… a box of free cigars.

Imagine yourself trying to bribe a Major League Baseball manager to let you play for his team with something that didn’t cost more than a few bucks. Just gathering up the courage to even ask something like that takes big-time guts and a hint of not-giving-a-you-know-what. But here’s the craziest part… it worked. Entering the final game of their season (and eventually franchise history), what else did the Spiders really have to lose? Nothing. But what did they have to gain? Potentially one of the greatest sports stories of their time. Also, a box of cigars.

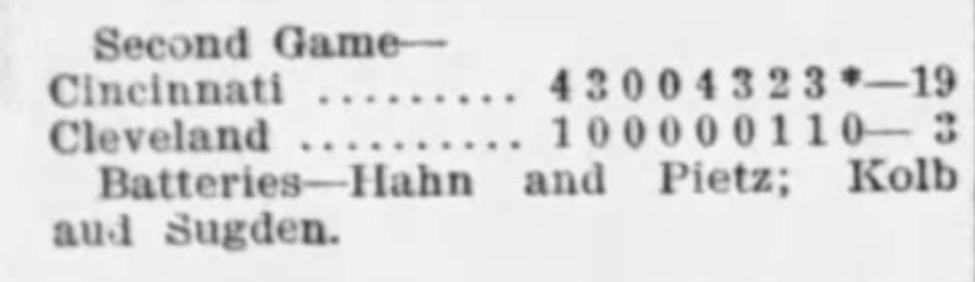

On October 16, 1899, 18-year-old Eddie Kolb stepped onto a major league mound for the first time in his life. It would also be the last time in his life. Before the days of sports talk radio, Kolb put the “I could pitch better than that guy” theory to rest as he allowed 18 hits and 19 runs (nine earned) while walking five and striking out one in eight innings.

Realistically, most of us will never live our biggest, wildest dream. Eddie Kolb did. At the end of the day, does anyone care that he got his clock cleaned? All anyone really remembered was that Kolb, just a teenager working at a cigar shop, pitched a Major League freakin’ Baseball game. It was even mentioned in his obituary, despite Kolb spending his adult life as a restaurateur and oil man in Canada.

Edward William Kolb, once known as Eddie and later “E.W.”, failed at baseball his entire life. He never made it back to the big leagues, his attempts at buying a minor league club proved unsuccessful and eventually he had to settle down and work a “real job” like many men that came before and after him. The worst moment in a baseball team’s history was quite possibly one of the greatest moments of his own life. To many, this would be a sad story. But not for him. Despite never reaching the heights of glory that he may have wished for, Eddie Kolb lived his dream. That’s something you can never take away.

And hey, he did go 1-for-4 at the plate.

It’s early Spring Training, friends, and whatever joyous adulations coursed through your soul at the sight of a 6’ 3”, 240 lb man in tights running with amusingly high knees and upright posture are surely already being replaced with a general sense of “Come on, man. Get to the good stuff.” I have been fortunate enough to attend Spring Training in Arizona many times and I am always fascinated (and a touch embarrassed) by how quickly I transition from worshipping at the warm temple of green before me to checking my phone for a good dinner spot sometime in the third inning. The charms of watching Chaz Levanesque face off against Gunner Williams-Williamson in the eighth of a 9-3 exhibition game are ruined in the digital age.

Now, I should be clear, I don’t intend for this to be another old white guy scolding a younger generation for a lack of attention span. In order to get to the loose concept I’m trying to get across in this here space we’re sharing I need to be honest: Spring Training is boring. As one of the great minds of our times likes to say, “No one denies this!”. Players and media alike spend precisely one week enjoying themselves before they grow anxious and restless for the tempo and trappings of a regular season big league schedule. That approximately one month into that experience they will begin to grow tired of it also, and the first pull towards the freedom and relaxation of the offseason will be felt, says something about the human condition and our inability to enjoy the present, but that’s a short to be relieved another day.

Today, I want to use the boredom and inanity of Spring Training as a backdrop for something I learned from Nelson Cruz in 2017. It was late March, and later in the game a 36-year old DH coming off three consecutive 40+ home run seasons should be playing a practice game. Cruz was facing some Cleveland pitcher of no consequence: Let’s call him Frank Bowowski. Bowowski threw a low and away slider on 1-2 that Cruz swung over the top of. The ball chopped off the plate and shot into the air twenty feet or so. I was close enough to the action I could hear the ball lowly humming with topspin as it arced its way between the mound and third base.

In a quiet, mostly empty ballpark in Peoria, out of zero obligation and at risk to his mid-30’s hamstrings, Nelson Cruz set off like a shot down the first baseline, setting off one of baseball’s many mini-ballets. Initially the third baseman and pitcher sprinted directly towards each other, seemingly engaged in an on-field game of chicken. Eventually a lifetime of experience and the spring’s recent deluge of PFPs led to the pitcher peeling off, leaving only the third baseman’s hard charge, clean pick up, off balance, side-armed delivery, the first baseman’s stretch (how many of us could accomplish just this simple portion of the play?), the ball hitting glove and foot striking the bag in rapid succession; “pap-pap”.

The umpire signaled out, and Nelson Cruz turned around, chest heaving and helmet lost from the exertion. He was smiling, a big, broad smile reminding me of what I know but often forget: Baseball is great, and I should enjoy it.

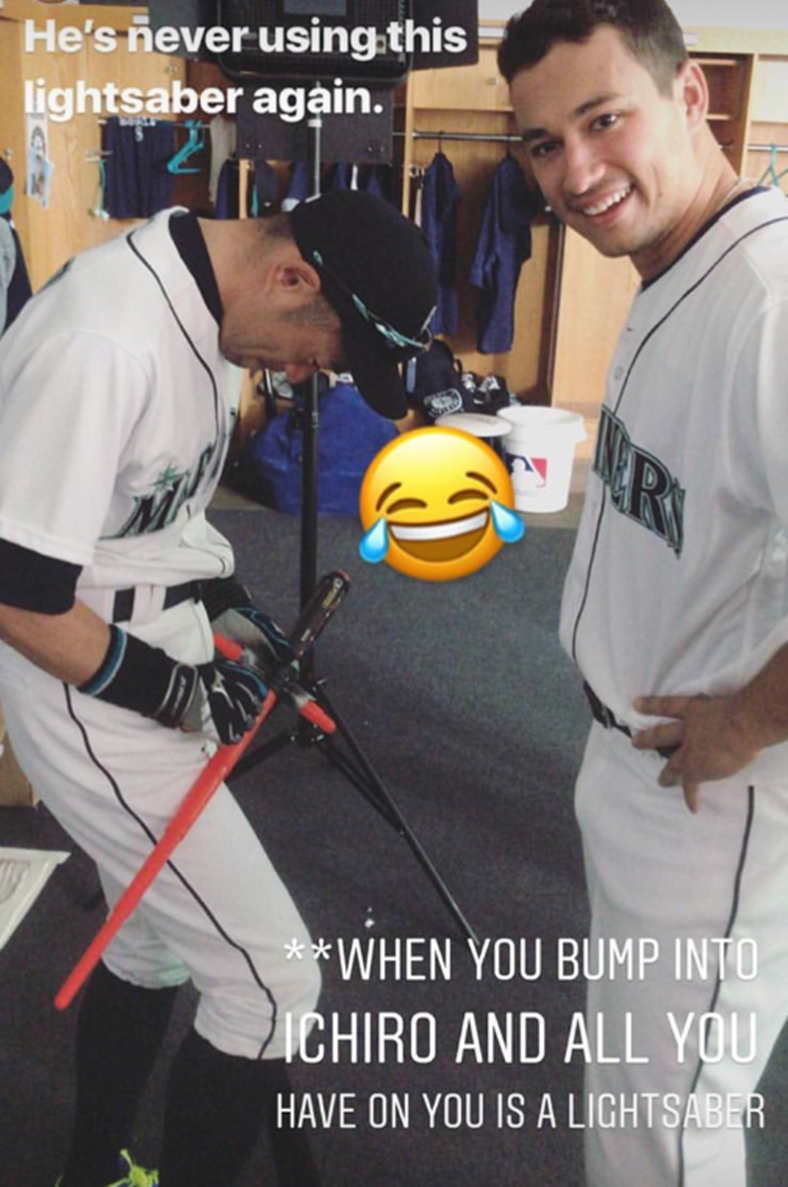

Smile. Just keep smiling, he’s a nice boy. Never mind that he’s as old as your career.

A good photo opportunity, perhaps convenient… an instance of a viral moment designed for the younger generation to post to their internet profiles: the dopamine hits arriving with each perceived ‘like,’ every slightly audible ding emerging from out the Mono speaker on the phones more powerful than our first personal computer. The vanity.

Don’t let him see it in your face. You know it’s a lie.

(Photo credit: @Cut4)

“All you have on you?”

You are a Major League baseball player, sharing space next to me in my Major League locker room. My locker room? Perhaps it is yours now, and while I appreciate the respect–I am aware of my history with this franchise, what they have meant to me–all I need is a rack upon which to hang my uniform, a spot on the bench.

What about cleats? A team-provided glove? A baseball? Hell, I could give you a hat, they have thousands of them in a huge bin hiding in the back. But it’s not about that.

A “lightsaber?” That’s what you call this thing? What’s the deal with the jet black handle?–I’ve seen the movies. A cheap commodity surely ordered from the shelves of Amazon, sent through postage drenched in the sweat of underpaid workers who have mere years before their replacement by the machine. Maybe he plans to sell it. I suppose its indexical relation to this very moment makes it superior to any old ball listed on the digital market. Or that’s perhaps what this moment means in the first place.

Smile. Just keep smiling.

You’re still writing your name wearing gloves.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now