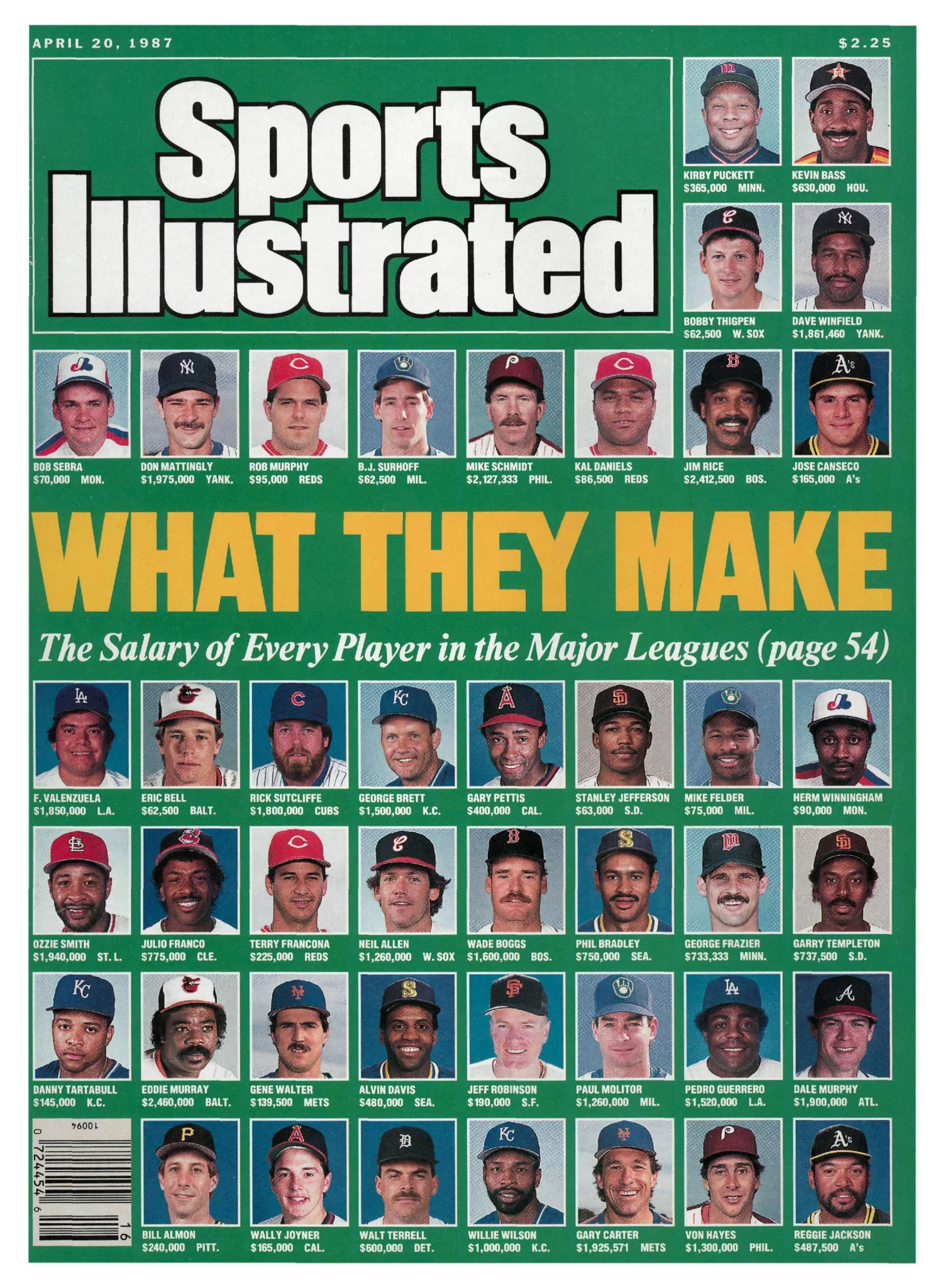

The cover of the April 20, 1987 Sports Illustrated does not feature the action photography one generally associates with the magazine. Instead, the pictures of 43 random baseball players, from Neil Allen to Herm Winningham, are lined like mugshots against a solid green background, along with their names, their team, and their 1987 salaries. The bold title, “What They Make,” has all the weight of an exposè, but the actual article begins with the barest of prefaces before devoting pages, phone book-style, to each major-league contract. Perhaps SI felt little need to editorialize, as though the evidence was damning enough.

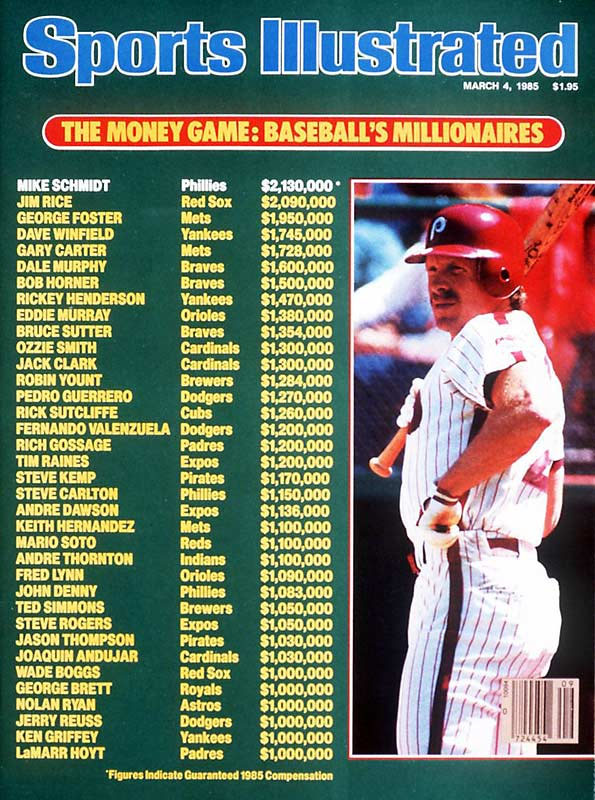

It wasn’t even the first time the venerable publication had tackled this story; two years prior, the cover itself provided a list of baseball’s millionaires, though it should be noted (as it was not at the time) that baseball player millionaires is the accurate description. The owners, naturally, were omitted. That article focused on the dramatic rise in salaries, not through free agency, 10 years old by that point, but through the secondary effect of arbitration.

The title of the 1985 article is “The Money Game,” but it may have been a last-minute amendment, because the page headers in the article are rather ironically titled “Moneyball.” It’s fitting, given that finance has been tied to modern baseball analysis since that book took hold in the public’s imagination. The path from those early days of “building a team without being able to spend” to “building a team without having to spend” to wherever we are now, the dreaded and anticipated free agency season of 2018-2019, can be plotted with a straight line.

It’s a little strange that we even know what baseball players make, given that we’re unlikely to know the salary of the man or woman who sits next to us at the office. Contract details aren’t technically official information; they’re never included in team statements, but always provided mysteriously, and reliably, by reporters moments later. But then, every aspect of a baseball player’s work life is so ruthlessly examined and reconciled—imagine how many 0-for-4 days you’ve had in your own professional life—to the degree that a salary just feels like another statistic, a talking point at the bar. “Can you believe Von Hayes makes more than Paul Molitor?”

This article existed, continues to exist through the internet and our very own Cot’s Contracts, because we want to know. When we hear that our favorite team signed a player, our first reaction tends to be: What’s the contract? Did our team get a steal? Baseball fans can’t escape the front office perspective that has been baked into us by team mouthpieces, $/WAR-based analysis, and fantasy baseball management. The money is part of the game for us, as foreign as it seems that we have to use that very same currency to buy $10 stadium beers. But because of the nature of ownership, and the arcane magic that is accounting, we’ll always be reading exactly half the story.

***

Words carry connotations. Everyone knows this. You can call a piece of writing succinct, or you can describe it as terse; each might be accurate, but each might also be telling you how to feel about the information you’ve been provided. The Greeks got up in arms about this 2,500 years ago, called it sophistry, and then spent a generation fashioning a negative connotation around the word sophistry to remind everyone how bad sophistry is.

But numbers can be just as easily weighted, and not always so easily perceived. The toddler-level deception is setting a price ending in 99 cents, or the high school version, mislabeling a graph. But figures can take on massive, sometimes unintentional collective action problems: grade inflation, or the crippling nature of a three-star review. But for our purposes, the connotation present in every contract, every transaction, is opportunity cost, the things you can’t do because of what you’ve chosen to do. If you choose the pancakes, you’re not going to have room for the huevos rancheros. If someone recommends a book, they’re essentially volunteering eight hours of your free time. And when a team signs a baseball player, they rob themselves of the opportunity to sign other baseball players.

Because Moneyball came in the era of Davids and Giants, it made sense that we accepted these constraints. And they still made sense in this decade, when applying them to the kind of mid-market clubs that enjoyed free agency as a team-building exercise. But baseball budgets can’t be used for analysis; they’re a fantasy. The dollars-per-WAR model works the way it does because we understand exactly how players make money, how the system rewards (or fails to reward) their performance, how the aging curve will likely affect their future value. We understand the system. But we can’t make those same assessments regarding opportunity cost, because those systems are closed to us. We know what teams can spend only because of what they tell us, and every once in a while (30 years, just after that Sports Illustrated article) they suddenly all say exactly the same thing. It’s weird how that happens.

The question becomes: Is a player’s salary essential information? There are all sorts of inessential baseball information out there, uniform numbers and ejections, that we keep track of, because keeping track of things is fun. But it seems that we’re unable, in the public discourse, to extricate the trivial details of player salaries from the connotations that come with them. If that’s the case, then, can we ever accept a specific and limited budget by which to apply that salary as a useful detail?

I don’t think it’s possible. The financial equation of baseball was once fairly simple: teams made money by selling tickets, and sold tickets by fielding good baseball players. Buying the rights to stars, or after 1975, signing them, was a simple investment calculation: will he be worth it? Now there are television deals, MLB Advanced Media, concessions and merchandising and jersey sales and suites and foreign markets and subsidiaries. Ticket sales are only loosely tied to revenue. Even with open books, baseball teams could lose money while still making their owners (who own the local TV network) wealthy.

It should be noted that there’s a very good reason for baseball players to know each other’s salaries: it drives them up. That was the root of the 1985 SI article: that because everyone knew what Extremely Average Pitcher Walt Terrell was worth, other players facing arbitration could suddenly compare themselves to Walt Terrell, rather than just ask for a raise from their previous salary. Having this knowledge destroys the prisoner’s dilemma that each player had going into negotiations, cut off from all the information at the owners’ disposal. But while it’s good that players know what players make, that doesn’t mean it serves them for us to know it, especially when the performance of the millionaire is so visible to the common fan, so easy to deplore, while the actions of the billionaire are cloaked behind the veil.

We know so little about the finances of MLB teams, and it’s impossible to know how much of what we’re told is true, how much teams really are struggling with payroll and the luxury tax. It’s easy enough to guess, given the rise in team valuation and the demand in public financing for new stadiums and the explosion of new revenue streams. But even if we were able to dismiss those, it doesn’t matter: the fact is that we don’t know, that we’re not allowed to know. It doesn’t get to be part of the grand game we play with other people’s money.

***

The final irony of that Sports Illustrated cover is that we all know already what baseball players make: They make baseball, the product that we consume and enjoy. They did it when the ballplayers made $5,000 each and they still do it when they make $500,000. And like then, the teams with the best players tend to win.

Recently, the Mariners signed Yusei Kikuchi. We analyzed that transaction, and also noted the financial repercussions of the deal, not so much for Seattle (whose budget reads more like an obituary) than for the Seibu Lions, who could run afoul of their own run-in with MLB’s magical accounting skills. But for the people still somehow attending T-Mobile Field next year, it doesn’t really matter how much money their new pitcher will make; all that matters is that when they arrive on Opening Day, Wade LeBlanc won’t be taking the mound. The Mariners are better than they were.

Perhaps that’s not compelling journalism to leave it at this, in the narrative age of year-round baseball. (But we might, after these last stagnant few offseasons, be departing that age anyway.) And it almost certainly wouldn’t be good customer service. People do want to know the financial side of baseball, analyze value through it they same way they do batting average and WARP. But that curiosity runs into the chasm between players and owners and our collective reaction, as media members and fans, is to mostly shrug. By nature, every baseball team has two separate goals: to win and to profit. As those drift apart from each other, it becomes increasingly important for people to find new ways to exert their will on their private corporations of choice to focus on the latter.

But I wonder, just wonder at this point, whether it’s possible to provide this fiscal information ethically, knowing that we can’t provide the rest of it. Can the media discuss player salaries without inherently diminishing player salaries and providing pro-ownership propaganda? I don’t know yet. But if your team of choice signs Bryce Harper, I would suggest that you fight that instinct to imagine what the 10th year of the deal will look like. Just be happy that you get to watch Bryce Harper play. It can be as simple as that.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now

You're right, though: It is harder for trades, because those kinds of deals allow teams to say that they're trying to set up their next window down the line, and that the savings are secondary. We as media can still ignore the salary dump and concentrate on the present vs. future dichotomy, and then maybe write separate articles on the side saying that teams shouldn't be saving as much money, because young players shouldn't be so ridiculously underpaid.