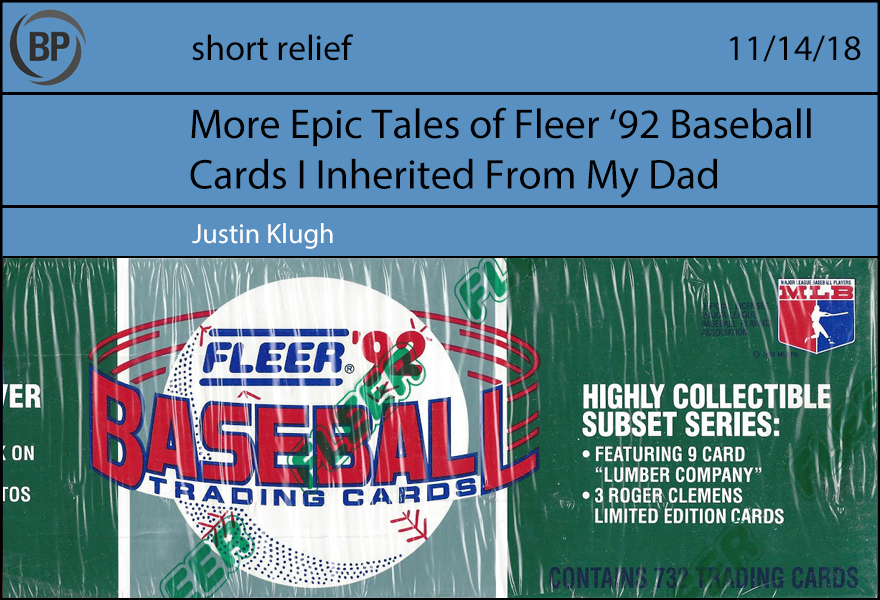

He was always in the cage or in batting practice, taking a few more cuts to get his reps in. Until one day, it hit him: Why take more swings, when he could just swing more bats?

“Old Three-Bat Thomas,” called him. “That’s not going to help,” his teammates would shout from the dugout. “If anything, it’ll make things worse.”

And it did. Opponents watched in confusion as “Three-Bat” laboriously waved at meatball after meatball, growing more and more desperate. Coaches, trainers, and specialists all tried to explain the folly of his plan, but he would just stare at them, eyes glistening with intensity, never saying a word, until they’d slink away.

Teammates began hearing him talk to all three of his bats, each in a different language, muttering at them as they leaned against his locker or rode next to him on the plane, and then nodding or laughing at their responses.

Finally, after an 0-for-6 day, Thomas left without speaking to reporters. He entered the clubhouse the following day, pale and shaken, the scent of flames lingering on his uniform and carrying only a single bat. When asked what had happened to the other two—his teammates hadn’t seen him without all three for months—Thomas responded cryptically, “They’ve gone home together.”

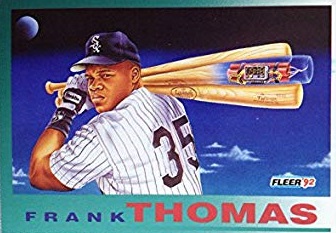

Everyone remembers the Ripken Wall, a featureless cement structure each member of the family has added to over the years. At least, that’s what the plaque says. But the other Ripkens have never publicly addressed the wall that Cal Ripken appeared in front of outside Camden Yards, leading to speculation that the plaque is wrong.

Before each Orioles game, he would appear in the lot in full uniform, and chisel an updated number for his consecutive games streak after filling in the previous day’s number.

“Isn’t the game tonight in Oakland?” passersby might ask.

Ripken would reply with simply the gentle, inquisitive smile depicted on this card, following them with his gaze until they were out of view.

And then, finally, Ripken broke Lou Gehrig’s streak. Some say he emptied the fragments of the demolished wall through holes in the pockets of his uniform pants while making his famous victory lap around Camden Yards. Others say it was carried away by a flock of orioles who appeared out of season in the dead of winter and dropped it somewhere through the ice of the frozen Chesapeake. But true fans know the real Ripken Wall was less of an actual wall and more of an idea: That man can achieve the impossible, needing only a gentle smile and an unbreakable body.

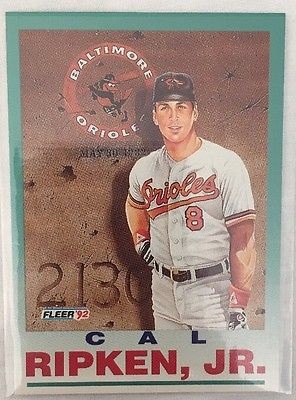

Some say the legacy of Ken Griffey Jr. was cut short by injury. But the true story, as this baseball card tells us through context clues, is that Griffey returned to his home world to be at peace.

He took back with him a relic of his years spent frolicking with the primitive humans: a wooden stick, used to smash a ball as hard as he could. While trying to explain the game to those of his species, Griffey found himself teased and antagonized.

“What a foolhardy game is this!” they would shout. “So primal! So simple! Not like our sports in this world, comprised of indecipherable algorithms and determined by metaphysical atrocities! Last year’s championship ripped a hole in the space-time continuum!”

He tried to convey the complex mathematics that make up the modern game; the focus on individual matchups, the value of OBP over BA, the methods by which baseball managers use numbers as a window into the future.

“What a boring game this is!” they would shout. “Much too slow, weighed down by lengthy evaluation and needless equations! Just let them play, as we do in our sports, the purity and gamesmanship of which are unmatched!”

And Griffey realized, as on earth, there was just no pleasing the masses, and he was called back to our planet by a love for the game, and also a lucrative marketing deal with Major League Baseball.

In much the same way you don’t realize your parents were Normal People until you hit your thirties, you never really realize that your teachers really had no idea what they were doing. I don’t mean this in the ontological sense—of course they know the content of what they were trying to squish into your brains–it’s rather that they really had no idea how anything would go once they drew up the plan, how you would take it, if it would make any sense to you at all whatsoever, if you would retain any knowledge or be excited about a new concept or simply just fall asleep at the behest of it all.

You remember that lecture. That one unit where you sat rolling your eyes drew cartoon characters on your notebook paper, or depending on your age, snuck a gander at Facebook. It’s because whatever they were jabbering on about at the front of the classroom made no sense, and you realized you were fine to bide your time until the clock ran out doing literally anything else and you hoped that nobody would notice you and that the evening sun would come to free you from your shackles like the cave Plato dreamt up thousands of years ago. But you never realized that they knew it, they knew what was happening as soon as your eyes pointed downward, with every performative no, I’m actually thinking please don’t single me out. A duel where both sides fall victim, the only one aware of it is the one who has the least to lose.

Yesterday I crafted a two-hour lecture that catastrophically failed to pique my freshman college students’ interest. I suppose the real failure wasn’t that they weren’t interested—who wants to take notes over having fun—but rather that I completely blew it. And as I saw the faces lost in confusion I realized the impasse wasn’t their fault, that I had thrown a heater over the middle of the plate.

But the fourth frame missing from this panel is the one I find most interesting. You know it—Charlie Brown sits up, picks up his clothes and re-dresses himself and starts over knowing the result is probably going to be the same. I don’t have to wonder what the impact of the ball felt like, but rather, I wonder what he saw when he squared up to try to get the next batter out.

Once, I think I was eleven, we played a baseball game. It was a Little League game, so by that definition it was “official.” There were umpires, scoreboards, lineups, coaches, bases, and uniforms. We knew the rules well enough to take first after ball four, and trudge back to the dugout after strike three. There was even a high probability most kids would remember when the third out had been recorded and change sides, although admittedly that got a bit more dodgy in the later innings.

For any child gifted with above average speed and athleticism, a key play in non-elite children’s baseball is the intentional pickle. In higher levels of the game, finding yourself stranded in between bases is almost certainly a death sentence. However, shave a few years off the players, and standing out in the base path, daring the player with the ball to either chase you or throw it to a teammate, is a viable baserunning strategy. This brings us to Anthony, who was the fastest kid on our team, and knew that fact all too well.

Anthony hit a ground ball to third, and the usual childish bumbling took place. The third baseman first kicked the ball, retrieved it, then threw low to the first baseman, who allowed it past him to the fence. Anthony, assuming all this would play out exactly as it did, sprinted to second before casually walking about ten feet off the base, intentionally marooning himself. The first baseman, mindful of his coaching, held the ball out as far as he could in front of him with his bare hand while sprinting directly at the baserunner. Anthony, unconcerned, simply stared at him.

At last, with the first baseman no more than five feet away from him our spry little Anthony shot towards third. Seven out of ten times this would be it; the player with the ball would panic, haltingly run before trying to throw and in the terror and confusion end up throwing it past the third baseman, allowing an easy and cheap run to score. This, however was one of the three in ten times, and the third baseman not only received, but cleanly caught, a chest high throw. When Anthony’s still confidence-filled, carefully planned retreat to second resulted in another successful throw and catch, to a second baseman who had managed to get in the proper location no less, things took a turn.

The one thing you never, ever expect in your typical Little League game is prolonged competence, but here they were, a group of prepubescent gibberlings hammering out a little baseball sonnet on a gray, chilly northwestern afternoon, one throw and catch at a time. Back and forth they went, Anthony’s eyes and panic growing larger with every successfully executed toss. Eventually, a stalemate resulted. No one on the other team was fast enough to catch our little speedster, and he could not force the error that had, up until today, always come so predictably. At a loss for what to do, at the exact midpoint between second and third, Anthony rose upright, turned directly to the umpire, and did what you do in sports when you need a moment to think: He asked for time.

It wasn’t granted, obviously. The umpire audibly snorted, and, his plea for sanctuary refused, Anthony sat down, right on the dirt, and waited to be tagged out, which was done in short order by a bewildered and bemused shortstop.

There are too many fumbling attempts to grasp life lessons onto sports, but that day the experience of Anthony and the Intentional Pickle taught me one nonetheless: The more you need to call time, the less chance someone is going to grant it for you.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now