“You know I’ll never see Wrigley Field anymore, before my eternal rest…” – Steve Goodman

* * *

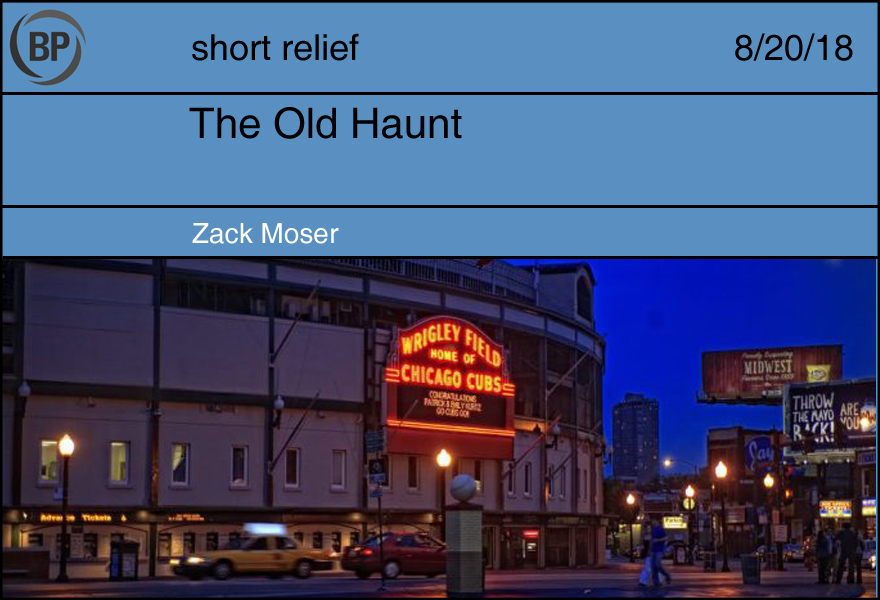

Last weekend, I returned to Wrigley Field for the first time since 2015. In the three years since, I’ve moved to Boston, cycled through several jobs, started writing for Short Relief, and entered a relationship long enough ago to be moving in with my girlfriend at the end of this month. In many ways, my life is much richer: my financial situation more stable, my depression more manageable, my career prospects slightly brighter.

Three years ago, Wrigley Field and its neighborhood looked much different than they did as I walked around the ballpark, popped into the brand new team store, and ogled the enormous office building, hotel, and apartment complex that have sprouted at Clark and Addison. Even the facade of the 104-year-old park got a facelift courtesy of the Ricketts’ enormous wealth: the pasty-cream stucco around the iconic red marquee traded for green wrought iron and (fake?) terracotta. It’s all impressive, imposing, and hollow. Wrigleyville has more DNA in common with Disneyland today than it does with the scuzzy, cheap neighborhood that, a few decades ago, attracted punks and the city’s queer population. Another piece might grapple with this in a Baudrillardian way, but as I walked through the concourse featuring all-new concessions, I simply found myself missing the incense of grilled onions that once permeated the ballpark’s innards.

* * *

My world is smaller today than it was three years ago, too, a little emptier. I wrote at the beginning of this season of my dad’s sudden death in February, two short weeks after he was diagnosed with cancer. Every day I grapple with it—some days better than others—and the acute anxiety of loss sets in once or twice a week. I’ll never be able to drive down to Wrigley Field with him and my mom and my sister, as we did almost every summer since our first game two decades ago.

The landscape of my world has been irreversibly changed, the ebbs of my days and months a little saggier and heavier without my dad. Some might reflect on the brevity of our lives, or the fleeting nature of the connections we make even with our closest family members. For me, I just miss something… the hiss of stovetops in hole-in-the-wall restaurants, the worn-in shading of old concrete, or maybe just that sweet stench of onions that my dad used to bask in as we walked the concourse, him searching for a Polish while I scoured the poorly lit concessions for a slice of pizza.

On Saturday, we watched a movie, in the theater, for full price. We don’t do this much. It was a mainstream Hollywood film, though one that has received positive notices and is regarded as genuinely important politico-culturally. It left me cold.

On Sunday, I watched a baseball game nearly live, mere minutes behind the action, and getting closer to contemporaneity every time I sped through an inning break. The contest was as important, emotionally, as an August baseball game can feel. The men in the booth said so. It left me overly anxious and ultimately disappointed.

It could be that I’m tired, nothing more. Work has been hell, after all, a deep and special kind of hell that one still can’t actually talk about because of pesky concepts like “attorney-client privilege.” But it has also occurred to me that this might be my new reality. The in-the-moment, the fresh, the live, is both too much and not enough. I can’t handle it, and I also don’t care.

I was told, after the movie, that I haven’t been liking things these days. On reflection, it’s true. Movies in my wheelhouse fail to move me; I spend more time nitpicking acclaimed TV shows than exalting them; I basically do not think about a baseball team amid an improbable run unless I’m watching last night’s game over breakfast. I don’t know if it’s age, or emotional wear and tear, or something worse and more troubling. Probably, like I said, I’m just tired, like the middle-aged seventh-inning man tends to get in the middle of August. And if I’m not? If baseball is now just a habit rather than a hobby? More obligation than object of enjoyment? I suppose there’s always retirement. I’m older than Andre Ethier.

Another ugly, smoky afternoon in August. You are lying on the floor because it’s the coolest place in the house, holding your phone precariously above your face. He sits above you on the couch, clicking through endless circles of Netflix suggestions in silence. The minutes ooze by. The ominous lines of red light sneaking under the blinds refuse to fade.

After the fifth time you drop your phone on your face, he throws the remote across the room and announces that you guys have to do something before he goes insane. You remember, as you put your phone on the floor and rub your lightly bruised nose, that there is a baseball game tonight. He’s never been. They’re in a playoff race. It might be fun.

“No,” comes the muffled reply. You sit up to see that he has rolled over and buried his face in the couch.

You venture a “why not?”

“No.”

This seems like the end of the conversation. You’ve already had similarly short conversations today, about going to a movie (all of them are stupid), or to a show (all the bands suck), or for a walk (it’s too hot, obviously). So you lie back down and look at the ceiling. You try to count all the tiny bumps. You get to 26 before he yells into the couch again. You guys have to do something before he goes insane.

You’ve been lying on the floor all day, and it’s only 5:00. There’ll be another seven hours of this before you can even think about going to sleep. You stand up, as though the suddenness of the motion will in itself cause some change in the situation, and you make your pitch to the body face-down on the couch: You’ll buy his ticket. You’ll buy him as many drinks as he wants. Minor-league baseball games aren’t that loud. You can explain everything, or, if he doesn’t want anything explained, you can say nothing. If he gets bored, you can leave. And it has to be better than this, anyway; anything would be better than this. There is enough desperation in your voice that you can sense it yourself, and you feel embarrassed.

“Okay, fine,” the body says.

Your seats are the best that were left on such short notice. Not in the grandstand, but down the right field line, where it’s still just a bit too much in the sun to be comfortable. The smoke hangs heavy in the air. You can see him frowning, an anomaly in no hat and no jersey, as you make your way back with two beers. The line was long, and the game has already started.

The batter swings and misses, and the crowd cheers. You feel an involuntary rush of excitement, and you look at his face expectantly. He takes a beer without looking at you and without saying anything, his glower fixed on the plate. Some kid behind you screams and kicks the backs of your seats. He takes a long drink. You can sense his annoyance growing, and your heart races with shame.

Your heart thinks about saying something, apologizing or defending yourself, but you know it’s too late. You’ve already been judged and found wanting. You will go to many more games that August, and you will go to all of them alone.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now