Next year will be the 100th anniversary of two events: the Treaty of Versailles, which ended World War I; and Babe Ruth being sold to the Yankees, which set in motion years of minor scuffles all across the Northeast corridor. Much of these skirmishes had to do with baseball players wearing different colored hats having varying levels of success. Red is the best! No, dark blue is superior. This went on for several years, bringing us to 2018 where the stakes have never been higher, yet disagreements have spilled over into kooky promotional events.

PawSox will host "Evil Empire Weekend" at McCoy Stadium on May 5 and 6. Any fans named Joe or Kelly will be admitted for free to the weekend's games, while any fans self-identifying as Tylers or Austins will be banned from the premises. #RivalryRenewed https://t.co/LQYnGQSzJ6 pic.twitter.com/XtllPNvgYz

— PawSox (@PawSox) April 19, 2018

Teams don’t necessarily have to like each other, but you’ll notice most other baseball teams don’t have a centralized antagonist — they just look sort of confused at all other teams, wondering why their hats look different, but ultimately move on with their day. Normally we see such deep-seated detestment in college rivalries, which means the Yankees and Red Sox are basically glorified #teens. And not the good kind of teens. Teens with hats and accents.

Before the centennial of a weird sports transaction takes place, it may be wise to broker a deal between the two teams, so they don’t destroy themselves, primarily because we don’t want to see this happen, especially not for 4½ hours on a Sunday night.

The terms, which should be enough for now:

1. Effective immediately, both cities dissolve their intricate network of sports columnists and radio hosts

2. Re-establish paths of commerce between both cities, meaning once per month, both teams voluntarily trade Mookie Betts for Aaron Judge

3. Ramiro Mendoza Appreciation Night every Thursday

4. Both teams now officially loathe the Astros, because somehow this wasn’t happening yet

5. Similar to a condition in the Treaty of Versailles, everyone gets new hats

Before mascots became anthropomorphic masses of fabric and terror and after they were live animals, they were human beings in baseball uniforms. Each mascot was supposed to bring luck to their designated team, helping imbibe the players with confidence and spiritedness, and each was jettisoned when their team performed poorly over a long stretch. There was no formula as to how mascots were chosen; some were picked because they were acquainted with a player while others may have made themselves noticed in the stands during a particularly crucial victory. Despite being the face of their team, many mascots were left nameless and without autonomy, eager to return to their lives where recognition was more personal and more fulfilling. However, some mascots, upon becoming mascot, found their mundane lives utterly unbearable and spent their years fruitlessly chasing the fame they achieved in the stands and on the field. This is one of those stories.

Albert “Pat” Reilly became the St. Paul Saints’ mascot in 1924, and though it is unclear what prompted the team to choose him, he brought the team ample luck as they finished in first place in the American Association. Reilly even managed to get into games on multiple occasions to provide the team’s stars with an opportunity to rest. In one such instance, replacing outfielder John Merritt, he doubled and scored a run. Despite the value he gave to the team, they moved on from him at the end of the season.

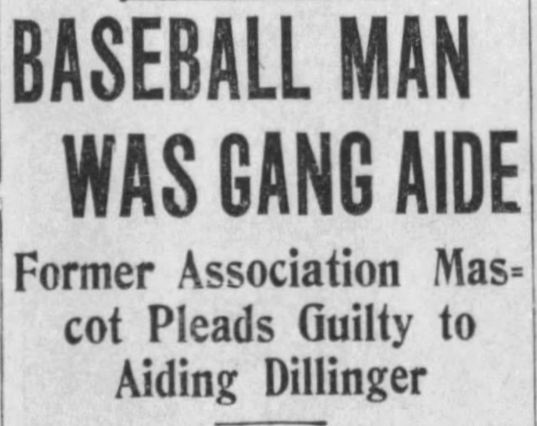

Reilly quickly moved on with his life, channeling his luck into other pursuits that garnered him headlines again a decade later, after providing another John with respite. This John, however, was of a far different nature. This John was famous Chicago gangster, John Dillinger. Reilly had been a member of Dillinger’s gang on-and-off for a number of years, but became one of Dillinger’s primary men upon the gangster’s release from prison in 1933. The pair spent much of the ensuing year hiding from police, using Reilly’s natural luck to narrowly escape arrest on a number of occasions.

However, as with the Saints, Dillinger parted ways with Reilly after a few short months. Five days after Dillinger’s death, Reilly woke to find police surrounding his bed, and he was soon charged with harboring a fugitive. Two months later, Reilly pleaded guilty and was sentenced to 21 months in prison and fined $2,500. Throughout the trial and sentencing, Reilly was characterized as a man obsessed with fame and greatness, one who would have done anything to be remembered, one who grew close to Dillinger precisely to be remembered.

Unbeknownst to him, his biggest claim to fame occurred a decade earlier.

Portland is getting a baseball team!

Or–in case you didn’t hear–haha, no they won’t.

It’s a tale that began in the early nineties, woven with free-market-expansion theology and shaped for the 21st century with bloated contracts and public-financed stadium deals. I grew up in the city watching the Seattle Mariners play on national television, heard Dave Niehaus talk on my Sony boombox through a network affiliate–and that was supposed to be good enough. I always wanted a team of my own, living there, in Rockcreek, Oregon, but instead the sport handed me SNES games with Griffey, and the television.

To be honest, I had lots of thoughts about this as I spent my early twenties in Portland proper. What do I do with the fact that I’ve invested x-amount of emotional labor into following this stupid Seattle Mariners team despite the fact that I have to drive three hours to see them lose a Tuesday night game against the A’s with 7,000 people in attendance? Instead, I turned to fantasies of opportunity: it would become a super hip thing, like the Timbers. A small stadium, and oh my god, Portland folks love to be the most of something, even if its the smallest of something.

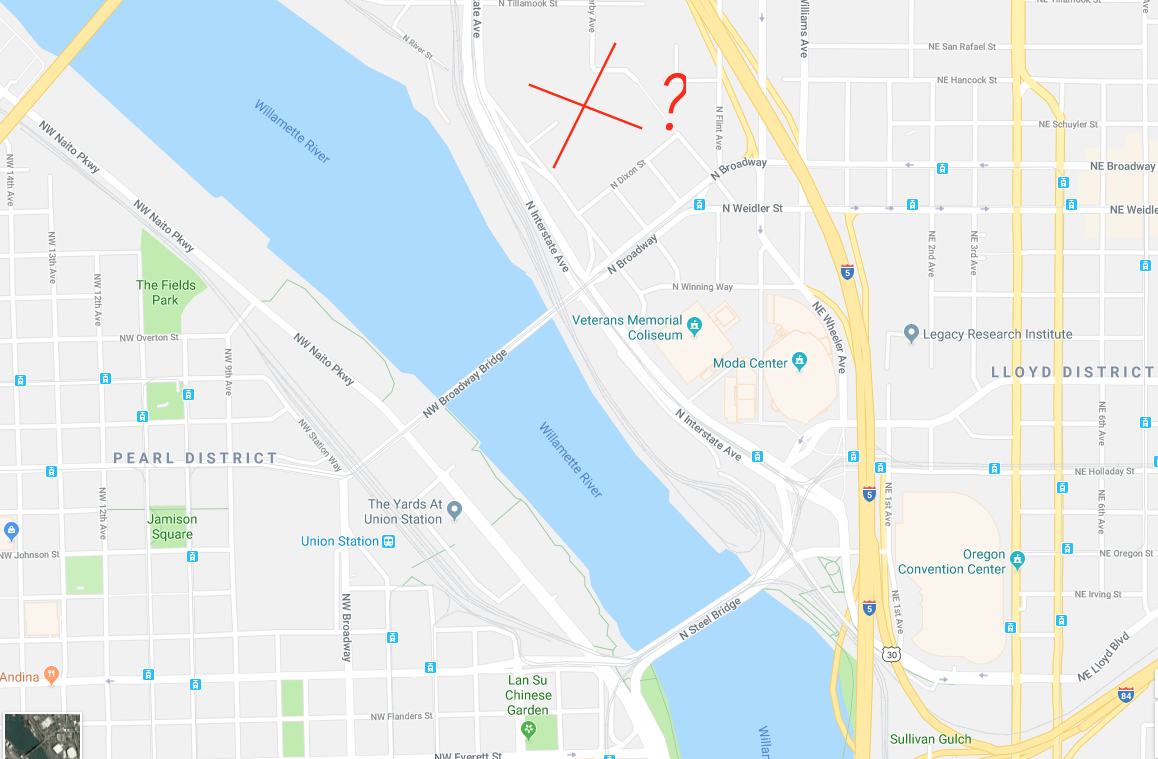

But then I looked at the possible places this new ownership group is posing for the stadium and I realised something about history, and time, that I will never be able to grasp in a meaningful sense otherwise. There are two main sites (outside a possible Lloyd Center buyout that might be happening with local Portland schools) for the new Portland baseball stadium.

The first? Well, the first is near the Portland Trailblazers’ current stadium, the Rose Garden The Moda Center:

As far as one would want to go to imagine building a twelve-block-radius of sportspubs and stadiums, this is clearly PDX’s best option for setting a small baseball stadium down, on paper. The area was mostly industrial warehouses until the middle of the 20th century, when it slowly began to follow the rest of Portland’s lead and pick up steam: spendy brewpubs, the convention center, etc. It’s easy to level parking lots when you don’t quite realize the neighborhood right above you might suffer, but at the very least how great would it be to walk around rooftop pubs going from playoff basketball to spring baseball at your leisure? Enter: Portland’s baseball history.

The second site posed for the expansion is, eerily, near where the Portland Beavers’ original park stood for the first half of the 20th century until their relocation south, across downtown. In fact, as Kip Carlson points out in his book on the Beavers, this stadium is in part responsible for the neighborhood in Northwest Portland as well as the tracks stitched into the concrete streets that eventually gave way to the above-ground subway system–the MAX–that first existed to bring people to see a minor-league team when the PCL could very well compete with the American League before television and radio.

But today, this neighborhood is filled with high-rise condos and warehouse brew pubs. The history of a city like Portland is the history of a city that in one sense slept through two phases of urban development, and woke up before the last. By putting this stadium in the latter neighborhood, one demands an allegiance to simulacral history, while the former begs for a future which sees no contradiction in financializing lower-income minority neighborhoods to suit the needs of a growing city that doesn’t yet know the limits of where its britches end. And in the interim, the Seattle Mariners will continue to purchase billboards advertising for their televised product on ROOT Sports, and the population will ignore them, as they always have. The choice is theirs–or is it?

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now