This past weekend I found myself at a Goodwill, as one does when one has children who somehow go through pajamas faster than they go through meals. While sustaining the basic needs of said offspring, I discovered one of my favorite things: a monster box of baseball cards for seven dollars, filled with the usual assortment of junk wax pyrite. I rarely keep many of the cards, but I enjoy the exploration; it’s like reading an unwieldy old magazine, or a shoddy, hastily made time capsule.

I did not make back my investment, but I did uncover something sadder: 187 Mike Greenwell baseball cards, organized by year, make, and brand. Mike Greenwell is not the worst-looking man in America, but he also does not at first appear to require nearly two hundred photographs. Most focus on the same two archetypes. There is the stiff follow-through, head often searching groundward, bat held in various expressions of confidence. And then there is the Greenwell at ease, tense even when trapped within history and cardboard, lips pursed in various attempts at smile. In both examples the eyes are the same, regardless of age, regardless of fortune. They must have known what the child hoarding these baseball cards could not imagine.

That child believed in Mike Greenwell, went out of their way to collect duplicates, gather as much of the man into their own life as they could. 187 Greenwells out of hundreds of thousands, but 187 times more powerful than one. One can see the crest of hope: one rookie card, at a dollar too expensive for a child in 1989. One card from 1997, probably picked up as an afterthought, as Greenwell’s back and the card collecting hobby both faltered. Many in betewen, the symbol of a limitless expanse of childhood, quickly punctuated.

But the mystery! Whoever it was, they kept these cards for twenty years, long after his career was forgotten, consigned to some dark closet corner, or worse still, preserved by some well-meaning, devoted mother. Until finally the time had gotten to be too great, and to Goodwill they went, to make room for some new, untarnished dream.

And now they are here. I do not care for this man, who once drove in 9 runs in a single game, long ago. But I care for the care that went into these cards, the pathetic and beautiful idolatry. I do not want to destroy the evidence of love that went into their order. But my closets are also full. This is the way of the world; that it is not just people who die, but dreams, and these mustachioed photographs of Mike Greenwell are the sparrow that has struck my window. I must bury them, just as I hope someone will bury the last copy of these words.

VANCOUVER, BC — In a world where takes of all temperatures flow like so much water over the eyes and nostrils of the logged-on sports fan, one “baseball writer” has made a bold decision that threatens to upend the status quo of “baseball writing” forever.

Rachael McDaniel, whose work can primarily be found crumpled in recycling bins across the University of British Columbia and, like, at least eight pages deep in a Google search, has announced a shocking new direction for the upcoming season: McDaniel’s baseball writing will never again feature any opinions on baseball.

“I feel around my neck, even in dreams, the cold grip of anxiety choking me slowly, to the point where it seems like if I try to scream only the barest whisper will emerge,” McDaniel, communicating from under a mountain of Blue Jays branded blankets via notes scrawled on torn-up McDonalds napkins, says of the unprecedented choice to avoid expressing anything resembling a take on the sport.

You might think it would be difficult for someone who gets paid to write commentary about a thing to avoid injecting their writing with even a hint of opinion about said thing. But McDaniel is confident. “Any time I get tempted to express myself, I look at what people on the internet say to other people who express themselves,” McDaniel says through a series of increasingly hard-to-read napkin shreds. “I personally don’t need some rando online to accuse me of being a triggered [expletive] pushing an agenda for having an entirely uncontroversial opinion about the sport with the big men throwing the ball really fast. I have enough real problems as it is.”

But doesn’t the world need a fresh, challenging perspective on America’s Pastime? McDaniel, who is now writing on napkin shreds less than a centimeter wide, doesn’t seem to think so. “There are a million other people sharing their baseball opinions out there. No one’s going to miss mine. I’ve got a laptop and an MLB.tv subscription and I’m going to sit in here and enjoy my goddamn baseball in peace. Leave me alone.”

When asked whether there is any concern that the move away from having a take on any baseball topic ever again might limit a hypothetical audience, the towering pile of Jays blankets under which McDaniel apparently resides shifts slightly, and a muffled voice can be heard. “I don’t know. I’ve already said too much. You have to leave now, or else I’m going to get excited and start talking to you about women in baseball again, or about the Jays signing Oh, and this all will have been for nothing.”

photo credit: © Gary A. Vasquez-USA TODAY Sports

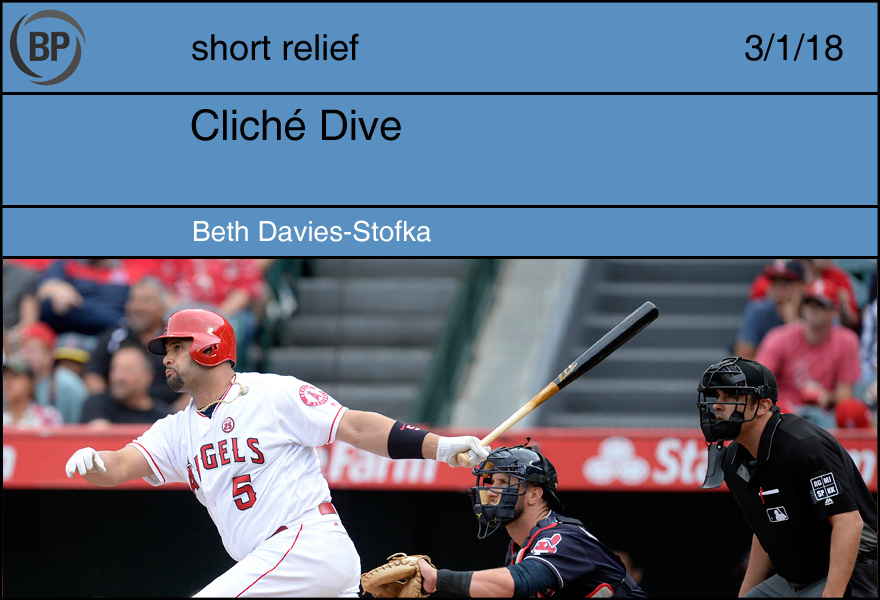

I was late to my first ever spring training game. It was on a hot Sunday and I’d gone to see the Angels play. Just as I stepped onto the concourse, I heard the crack of an Albert Pujols home run; he hit it just before I reached the railing. I could see his regular season face, focused and determined and worn for a practice game. The infielders rotated into position as he began his sprint, and the two guys in center and right raced to catch a ball that we all knew was leaving.

Above the action I saw the ball, arcing gracefully towards the parking lot.

Frozen in place, I savored it. I knew it was a home run like a million others. I knew it was spring training and the home run didn’t matter, not really, not in the way it would to an 11-year-old kid on a sandlot or a 28-year-old kid in the World Series. But it was an impossible coincidence. The very first moment of my very first spring training game, and I saw Albert Pujols hit a home run. It intensified everything for me. The sun was hotter, the grass was greener, and the sky was wider and bluer than it had ever been. It wasn’t, of course. But it was.

“No standing on the concourse!” The abrupt voice snapped my concentration. I turned in surprise and a grouchy usher herded me toward the stairs; I had to look down to keep from stumbling. He didn’t let me finish the moment. It’s forever incomplete.

Sometimes I’ve heard people say that baseball is like life. Back home, my football-obsessed friends enjoy the phrase. When they find out I love baseball, they nod sagely and say, “Yes, baseball is just like life.” They say it as if they were the first to say it, as if it explains why I don’t bleed orange and blue. I’m not normally open to their homespun philosophy because it’s only half true. Baseball is also not like life. It’s a relief from life. Baseball has rules. It’s mostly fair. It’s graceful and fun and there’s always tomorrow.

But on that day in Arizona, baseball really was just like life. Beautiful moments are brief and made more special because we pay attention to them. Sometimes we get interrupted. Sometimes, like a home run already hit, we just have to let it go.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now