(photo: © Kenny Karst-USA TODAY Sports)

The job doesn’t sound bad. It sounds pretty good, even—certainly better than the ice cream parlor where he’d had to sing for tips, and probably better than the telemarketing gig.

“Don’t tell anyone, but I actually think being the mascot’s assistant is more fun than being the mascot,” a cheery woman tells him with a conspiratorial giggle on his first day, handing him the scratchy polo shirt that will be his uniform. “Getting to have a good time out in the crowd and meet people, but without sweating in that heavy suit!”

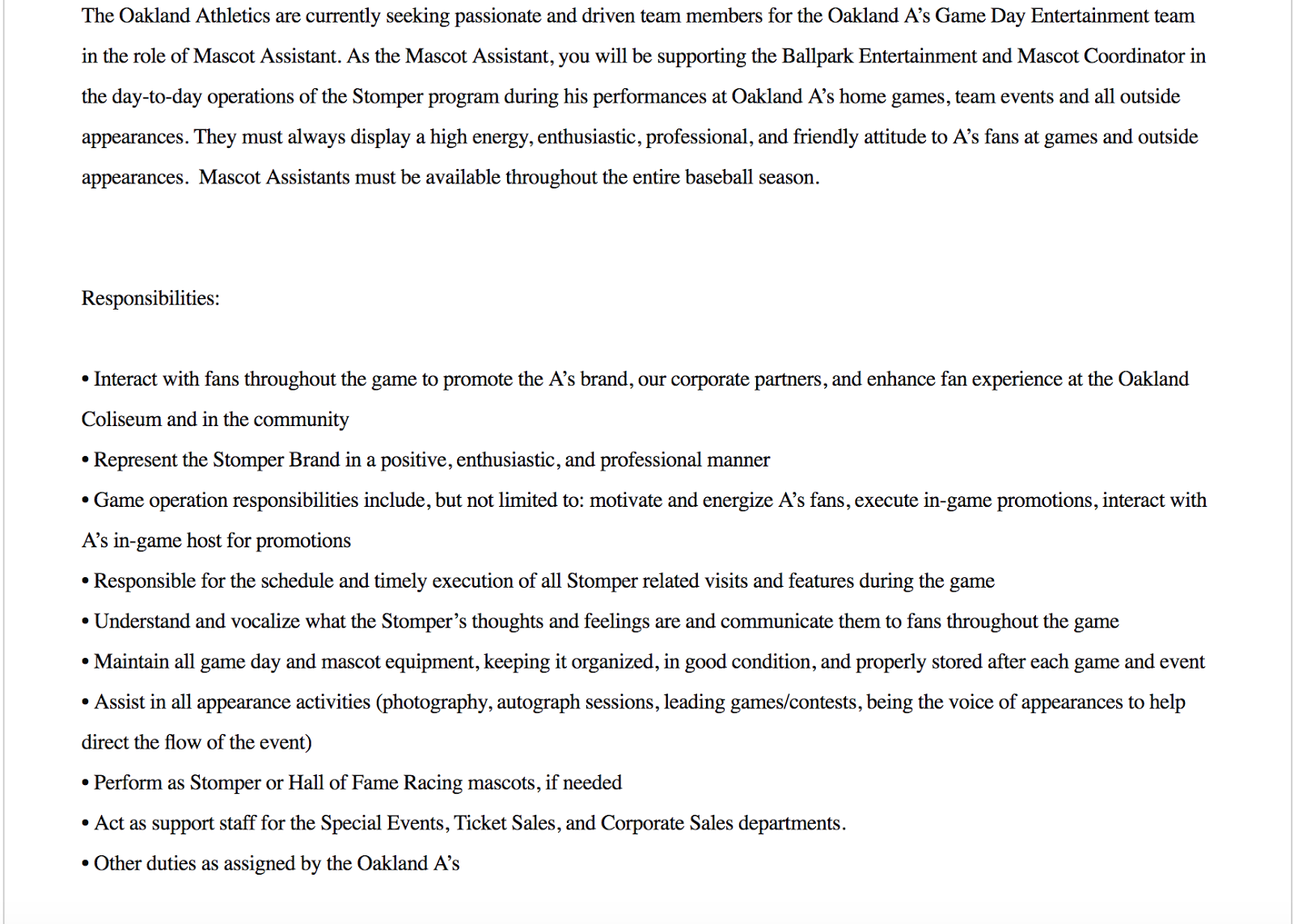

For the first few weeks, he thinks she was right. The job is usually simple and it’s often fun, or something like it. He guides Stomper around, encourages small children not to be scared of Stomper, does a bunch of minor clerical and logistical tasks that are boring but not soul-crushingly so. There is just one thing that is neither simple nor fun, and increasingly a problem. He wonders how it can possibly be a requirement of the job, but he checks and checks again and there it is, in the paperwork he signed on his first day and even in the job listing that he first saw weeks before that. Under “responsibilities,” sandwiched between the mundane stuff—scheduling Stomper’s visits around the stadium and putting away Stomper’s weird unwieldy head each night—is the task that kills him:

Understand and vocalize what the Stomper’s thoughts and feelings are and communicate them to fans throughout the game.

He hadn’t really thought about that line when he first read it; to the extent that he had—if he had, it’s getting hard to remember now—it was only to imagine communicating thoughts like “Go A’s!” and understanding feelings like “pass me a water bottle, please.” Maybe it was like that, when he first started. But now he has spent so much time looking into the plastic whites of those artificial eyes, and giving directions to those too-big ears that cannot hear, and clumsily feeling the outline of the human hand inside the bulky elephant paw while guiding Stomper down the stadium steps. Those eyes! From a distance, they look stupidly and maniacally happy, all wide and cartoonish. But when he gets closer—really close, too close?—he can make out the shadow of the other set of eyes, beyond the thick black mesh of the synthetic pupils.

Understand Stomper’s thoughts and feelings. He tries to look into the eyes behind the eyes, which he hates, but it is always better to look into that eerie dead-alive set than it is to stare at the mouth—permanent grin, steady glimpse of the same small section of felted pink tongue, no throat, no voice box. What does Stomper feel? The question always makes him too aware of his own body and all the ways it is not like Stomper’s. It shouldn’t be a question for him, anyway, he tries to tell himself. A therapist. A scientist. A mind-reader, maybe.

But it is a question for him, for the mascot’s assistant, and increasingly it is the only question. Yet no one else seems to ask it. The children squeal when they see Stomper and the drunk bros call him by name and everyone, everyone, smiles. They love him. They are not bothered by the hollow eyes with another set of less hollow ones behind them or the empty space between human and elephant—is there any?—in the furry suit or the mouth that cannot speak. They do not want to know what Stomper feels, or they do not care, or maybe they think they know already. It all makes him desperately jealous. He wants, badly, not to care. The question runs on a loop, through his mind and down his body, growing tighter and pushing out everything else and still there are no answers. What does Stomper feel. He stops trying to look Stomper in the eye and instead focuses on the little green hat that’s permanently attached to his head, neatly sewn on between the perfectly symmetric ears with smooth pink insides that do not open into anything. This is somehow worse.

Everything is worse. He whispers the question to the head one night as he places it back in storage—what do you feel—and stares at the eyes until he can see the shadow-eyes behind them and then he pushes the head all the way against the wall and leaves without shutting the door. He starts asking out loud all the time. What do you feel, what do you feel, what do you feel. He whispers it as he walks into the stadium each day, as he falls asleep each night, as he stands just out of frame while the crowd cheers for Stomper’s appearance video screen. What do you feel. Stomper falls down while running the bases, like he does every game. What do you feel. Stomper poses for a photograph with a sticky-fingered five-year old. What do you feel. Stomper smiles. Always; the elephant has no choice. What do you feel. He stops whispering. He says it out loud. His desperate panic melts into something so raw that it bleeds and he bursts forward up the stadium stairs and pulls at the elephant’s ears. He wrests the head off and forces himself inside. What do you feel. What do you feel. What do you feel

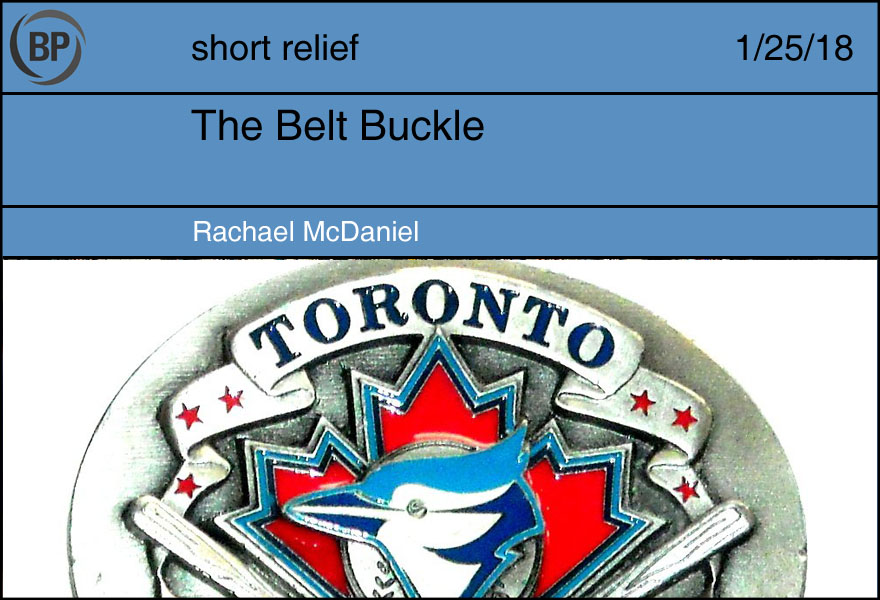

Some time last year my younger brother acquired a belt buckle. Not an ordinary belt buckle, mind you. This belt buckle is large—almost as big as my hand. It is a sort of an ovoid shape, like a sideways egg, and made out of some kind of metal that is both shiny and weirdly dark. Embossed on it is a huge, colorful Toronto Blue Jays logo. I don’t have the thing in front of me right now, so I can’t say for sure, but I think it’s probably late-90s era. It’s certainly not one of their better logos, but it does make a statement.

My brother found this treasure at a liquidation store, or maybe a thrift store—he was bored, rooting around in old stuff while my dad was looking for some less important object. When he got home he did some research on it, found that it was part of a limited run of 10,000. He was extraordinarily pleased with his find.

The only problem was that he has very limited opportunity to wear this belt buckle. He’s 11 years old, and 11-year-olds aren’t commonly seen wearing large, loud belt accessories. He also goes to Catholic school, and the sheer size of the thing probably qualifies it as a uniform infraction. So the belt buckle has stayed on his desk: prominently displayed, of course, but displayed in isolation, with only himself as an audience for how cool it is.

A few weeks ago, he and I went to an autograph session that the Blue Jays hosted in Vancouver. He was thrilled—he’d never had a chance to actually meet any of his favorite players before, and might not have another one for a long time in the future. I was less excited for the event than I had been a few months ago. I was feeling exhausted and sad, and bummed about the state of baseball in general. I didn’t feel like waking up to go stand in line just for a chance to exchange pleasantries with players who probably didn’t really want to see me and didn’t really care.

I tried not to let this color my brother’s experience, though. He was buzzing, and he had also decided that this was finally the perfect time for the belt buckle to make its debut in the wide world. On the way there, he peppered me with questions about what it would be like that I struggled to find the energy to answer. He kept asking me if I thought Marco Estrada and Justin Smoak would like his belt buckle. He really hoped they would. I didn’t want him to be disappointed, so I said that they would definitely think it was cool. But they might not say that, I warned. They were probably tired, and they had hundreds of autographs to sign. They probably wouldn’t feel like talking much.

We got to the place, and we stood in the line, and eventually we got to the table. By this point I was almost asleep on my feet. My brother went ahead of me. I stood behind him as he shyly said hi to Estrada. Estrada looked up from the thing he had been signing. He broke into this big grin.

“Hey, that’s a sweet belt buckle!” he told my brother.

And when he was done signing my brother’s jersey, and we moved along to Smoak, the South Carolina native smiled even bigger than Estrada had. He and my brother had an entire conversation about belts and buckles and that specific belt buckle that he was wearing. I couldn’t even catch much of what they were saying because they were saying so much. I suddenly felt less ready to pass out than I did before. I realized that I was enjoying myself.

As we walked away from the autograph table, my brother turned to me, beaming. “They liked my belt buckle!” he said.

“They did!” I replied, and this time it wasn’t a struggle to match his energy. We went out for sandwiches, wearing our new Jays hats, and talked excitedly about the season ahead.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now