My Troy Tulowitzki Jersey

By: Rachael McDaniel

I own one baseball jersey. It’s a Troy Tulowitzki jersey in the Jays’ alternate blues. I don’t wear it often—I don’t want it to get worn down. But I don’t want to hide it away or frame it either. So it hangs on my chair, the name and number facing outwards. It’s always in the same place, and I can see it from pretty much everywhere in the room. Big letters, big number. TULOWITZKI 2.

I’d coveted a Tulo jersey ever since I set eyes on him in September 2007. I wasted valuable minutes as a kid on library computers looking for used jerseys on Ebay, preferably ones that weren’t the weird black vests the Rockies wear. Sometimes I would find one that was pretty cheap, and I would try to plot out how long it would take me to save up enough to buy it, which, as a ten-year-old with no job, always ended up being a much longer period of time than I could conceptualize. So I tried to assess the value of my coin collection, a shiny tin box of special quarters that I’d been putting aside for as long as I could remember. There were a lot of coins, but certainly not enough to pay for jersey plus shipping. My humble dream of jersey ownership remained but a dream, and eventually, as I stopped caring about baseball, faded entirely.

By the time the Tulo trade precipitated my return to baseball fandom, all of my special coins were gone. I had spent them all on the bus in high school, after the third time I asked my parents for the $2.75 fare and they’d told me they couldn’t spare that much.

I had a job in the summer of 2015, but I still had no disposable income. It was minimum wage, and it wasn’t enough to afford two meals a day. When I started watching baseball again, because Tulo was on the Blue Jays, I watched it on choppy illegal streams with incessant popup ads and ten-second lags. I appreciated that I could get so much joy from something that didn’t cost me any money. I appreciated even more that it wasted so much time. That it made my days feel so much less empty, that it made me forget that I was trapped, unable to go anywhere or do anything, with no reason to believe that it would ever end. I skipped meals to put aside money for an MLB.tv subscription.

Tulo hit a homer in his first game with the Blue Jays, and I started looking at jerseys again. It was an exercise in self-hatred. I thought about how pathetic it was that I would never be able to afford even something as stupid and frivolous as my favorite player’s jersey. I thought about how pathetic it was that I still wanted it that badly. It became a symbol of all fears about my future. If I couldn’t even get such a small thing to make myself happy, what was I going to do for the rest of my life? I thought I already knew for sure. Bare walls and hunger, trapped and alone. Never able to do anything I wanted to do, no matter how insignificant.

Two years later, Tulo hasn’t set foot on a major league field since he mangled his ankle on July 28th. He is old and injured and not very good anymore. But I keep that jersey there, facing outward, and it makes me happy every time I see it.

Please Don’t Call It A Comeback

By: Patrick Dubuque

In 2016, Tim Lincecum arrived in a new town, wearing short hair and strange colors. It was a resurrection half-complete, a body brought back to life only to die again, drowning in the water in its own lungs. Then he disappeared, or so the narrative dictated: off to travel the path of Siddhartha, or sleep on the floor of Robert Swift’s dilapidated mansion, or whichever fate the Plinko board of life had decided to hurl him. Whatever happened, it would be the way it was supposed to be; the power of narrative clings to certain heroes, processes their lives into stories.

Yesterday, a new chapter began:

A new man, shorn and humbled, post-apocalyptic. Older and wiser. The stories will crash and recede like waves, reactions to reactions to reactions; that picture alone is a thing of promises, and by that one photograph he will come to owe everyone who sees him and places their hope in him. There will be setbacks read as betrayals, gallows humor, perhaps even a one-run, three-strikeout, seven-inning start in May. All of them dependent not on his will, or even his wit, but on the cells in his hip and arm, the ones that respond or fail when given the brain’s instructions. The story is already written and completed there, wrapped in double-helix; we just have to wait for the release date.

The story isn’t Lincecum’s to control, or even ours; it belongs to the maddened crowd, the thoughtless organism spun out of the invisible hand of Twitter accounts and radio call-in shows. It will demand tribute. But the story, whatever shape it takes, will be false: this will not be a comeback, or a failed comeback. There is nothing to come back from. Tim Lincecum was a fantastic pitcher, the best of his time, a champion. He may want to pitch again, but he does not need to pitch again. He owes nothing. We hold certain stereotypes of greatness, what it looks like, how long it needs to be sustained.

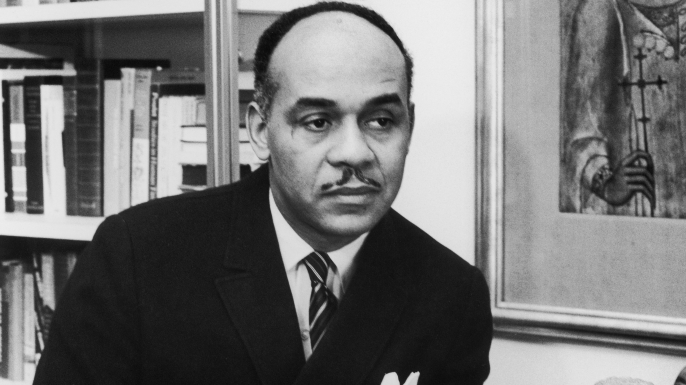

It’s not just for baseball; we do it for one-hit wonders in music, look upon authors like Joseph Heller and Ralph Ellison as pathetic creatures, unable to replicate their work, live up to themselves. It’s the wrong way to think. Imagine winning the Cy Young award once, imagine writing Invisible Man and pulling the page out of the typewriter and putting it into the world.

Ellison lost his second manuscript, not complete but hundreds of pages in a fire. It devastated him. He mourned it for a year, or five depending on who you ask, and then returned, only to find those years of work ripped out of him, like a torn labrum. He couldn’t go back. But he also didn’t quit, or die. He wrote essays, met with people, became a tremendous influence on the Civil Rights movement. His story didn’t end the way it was supposed to, but the path he did choose was no less a success. For Lincecum, it will be the same, even if it turns out that there are no more novels left in his arm.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now