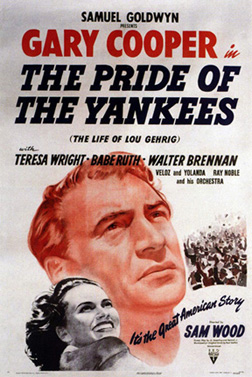

Pride of the Yankees (1942)

Genre: Inspirational biopic.

Logline: By virtue of a humility and an unrelenting work ethic, Lou Gehrig rises from a humble upbringing to be one of the greatest ballplayers of all time and find love, only to be cut down in his prime.

Starring: A trio of multiple-Academy Award winners, including Gary Cooper as Gehrig, Theresa Wright as Eleanor Twitchell Gehrig, and Walter Brennan as sportswriter Sam Blake (based on Baseball Writers Association cofounder Fred Lieb).

Also: Elsa Janssen and Ludwig Stössel as Mom and Pop Gehrig, Dan Duryea as Gehrig-skeptical sportswriter Hank Hanneman (a stand-in for Ruth ghost/future commissioner Ford Frick), and Babe Ruth, Bill Dickey (and Mrs. Violet Dickey), Bob Meusel, and Mark Koenig as themselves. Douglas Croft, who plays young Lou also played young Ronald Reagan in King’s Row and young James Cagney in Yankee Doodle Dandy that same year. The script was cowritten by Herman J. Mankiewicz of Citizen Kane fame.

Director: Sam Wood. He made several baseball films in his career, including They Learned About Women and The Stratton Story, before succumbing to paranoia and rabid anti-Communism. He was thrice nominated for the Academy Award for best director, receiving nods for Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1940), Kitty Foyle (1941), and King’s Row (1942).

How Realistic is the Depiction of Baseball? Not as bad as Cooper’s reputation for clumsy play would suggest, but not as good as you might wish. There isn’t a great deal of baseball in the film and that’s probably for the best as this isn’t a story about a ballplayer who happened to be a great man but rather a great man who happened to be a ballplayer. That necessitated trading baseball experience (Montanan Cooper had done a great deal of horseback riding but had never touched a bat or glove) for acting ability. From the moment the picture was made it was popularly understood that in order to compensate for Cooper’s inability to hit left-handed he wore a backwards uniform (“SEEKNAY”) and ran to third, then the film was flipped. Tom Shieber of the Hall of Fame has debunked that story. In actuality, former major leaguers and Pacific Coast League stars Babe Herman and Lefty O’Doul coached Cooper and got his left-handed hitting up to a passable level, with Herman occasionally doubling for him in long shots. His true deficiency was in throwing, where he was hampered by a chronically-injured arm. Cooper does look ungainly in most of his baseball scenes, but he’s also been directed to be ungainly as a matter of character. This is a strange choice given that however awkward Gehrig could be socially (and sometimes on defense) he was an incredible multi-sport athlete. But more problematic than Cooper’s play is his age; the film takes Gehrig from his college years through his age-36 retirement. Cooper was 41 and looked 50. Wright was 23 and could pass for younger, so the gap between them is stark. In actuality, when Lou and Eleanor began seeing each other he was 30 and she was 29.

All game footage was shot at Los Angeles’s Little Wrigley Field, then home of the PCL Los Angeles Angels. For shots looking out from home plate the screen is often divided horizontally at the midline, with Little Wrigley below and a matte of some other park backdrop above. This can be confusing because the backgrounds don’t always match their purported environs. Similarly, there are a number newsreel-type montages supposedly showing Gehrig playing with the Yankees. These are a hash of disconnected images spliced together from disconnected game footage—the film will suggest the Yankees are in St. Louis to play the Browns, then fade into footage of Billy Herman running the bases during the 1936 All-Star Game. (In fairness to the filmmakers, Herman does breeze past a ghostly actual-Lou Gehrig as he hustles into second.) Maybe the most egregious depiction of baseball comes in the film’s first few minutes when a young Lou is shown elbowing his way into a sandlot game. When the boy homers, the ball clearly comes not off his bat but from somewhere well offscreen.

Late in the film there is a nice touch of verisimilitude: The real Lou Gehrig had a number of small trophies he had been given over the years—watch fobs and the like—linked together as a bracelet for his wife. Eleanor Gehrig allowed Wright to borrow the jewelry (which is now part of the collection at Cooperstown). When Cooper bestows the gift in the film it is not a prop but the actual item that went from Gehrig’s hand to Eleanor’s.

Gehrig’s Gift in Pride of the Yankees

Real-Life Baseball Cameos: Ruth and Dickey have lines and get to participate in the story to a small extent. Getting to see them up close and hear them speak gives Pride historical value that goes beyond its qualities as a film. It’s a shame, though, that the filmmakers only included the ups and downs of the Ruth-Gehrig relationship in the most oblique of fashions and didn’t give Ruth a chance at a one-on-one scene with Cooper.

Bill Dickey and Gary Cooper.

Typical Baseball-Movie Cliché: Echoing the true Ruth-Johnny Sylvester story, Gehrig promises a sick child that he will hit not one but two home runs for him. “There isn’t anything you can’t do if you try hard enough,” Gehrig tells the boy and makes him promise that he’ll walk again. What’s intriguing about the scene is that it—aided by Ruth himself—suggests the Babe was showboating rather than sincerely trying to inspire the child. In reality, both Ruth and Gehrig were very generous in making themselves available to children, and a scene later in the film in which Gehrig is late coming home from the ballpark because he’s stopped to umpire a sandlot game probably isn’t the pure hokum it seems to be. The parallel isn’t literal—a Gehrig who avoided married life so he could spend his spare time with young children would have been (whether in truth or fiction) a very different character, and perhaps a disturbingly troubled one. Rather the scene suggests in exaggerated fashion a truth about the man and one of the things he and Ruth, for all their differences, had in common: Both took their obligations as role models very seriously.

Over 80 years since his passing, Lou Gehrig remains one of the greatest ballplayers of all time, someone who was almost indescribably good. Try looking at his statistics with fresh eyes, see pictures of him in his prime, and you can only just begin to imagine his power, speed, and dedication. Pride of the Yankees isn’t about that, but rather about Gehrig the tragic moral exemplar, a humble man who worked extremely hard, suffered a terrible fate, and bore it with almost Christ-like resolve. This is no doubt an eternal story, but although the appeal of the tale never changes, over time reactions to it might; the lesson the filmmakers intended for 1942 audiences might not be the same one audiences received by later audiences. Watching Pride in 2022 forces us to ask what Lou Gehrig means to us now.

It is impossible to miss that this is a wartime picture with a wartime message about doing your job without grousing and, if necessary, dying with dignity. The film begins with a written introduction by the New York sportswriter (and great chronicler of the Broadway demimonde) Damon Runyon:

“THIS IS THE STORY OF A HERO OF THE PEACEFUL PATHS OF EVERYDAY LIFE… A LESSON IN SIMPLICITY AND MODESTY TO THE YOUTH OF AMERICA. HE FACED DEATH WITH THAT SAME VALOR AND FORTITUDE THAT HAS BEEN DISPLAYED BY THOUSANDS OF YOUNG AMERICANS ON FAR-FLUNG FIELDS OF BATTLE.”

Later, Walter Brennan tells Dan Duryea why Gehrig was “better” than Ruth: “Let me tell you about heroes, Hank. I’ve covered a lot of ’em, and I’m saying Gehrig is the best of ’em. No front-page scandals, no daffy excitements, no horn-piping in the spotlight but a guy who does his job and nothing else. He lives for his job.” The great Gehrig was greatly self-effacing, displaying great humility as a player and great humility in death. These are all values necessary to men who might be asked to die for their country. Does Gehrig still speak to us if he can’t do so in quite the same way he did then?

Without the war we have one man’s tragedy instead of a lesson about how great suffering might be borne by a people under threat. In that sense the film becomes something akin to one of the “great man” series of pictures that Warner Bros. was chunking out around this time, biographies of forward-thinking fin de siècle figures like Louis Pasteur, Emile Zola, and Paul Ehrlich. They must have felt remote and dumbed down even then. Similarly, in compressing and simplifying Gehrig’s life the film makes a hash of his biography and of the Yankees/baseball chronology during his life; to fact-check the film would be to destroy it. It even bollixes the end of Gehrig’s consecutive-games streak; Babe Dahlgren is shown replacing Gehrig midgame, which would not have precluded him from starting the next day and tacking another game onto the total.

The picture does hit all the expected stations of the legend: The German-immigrant parents, especially the controlling mother and weak father, who didn’t want their only surviving child to sacrifice his education to a game; the friction between that mother and Gehrig’s wife; the broken friendship with Ruth; the physical toll of a consecutive games streak; the moment that Gehrig was forced to sit down. The film treats them all as discrete episodes, problems to be solved and dispensed with. As with all of our lives, Gehrig’s was not so neatly organized. Eleanor Gehrig never did reconcile with her in-laws, who sued her over Lou’s will after he had passed, and Lou never did wholly place his wife ahead of his parents, excluding her from family conversations by conducting them in German despite the fact that she did not sprechen sie Deutsch.

The fictional Gehrig is sober, chaste (his relationship with Eleanor is puppyish and only a few kisses past brother-sister territory), and almost saintly. While the real Gehrig was sober and chaste—or at least more so than the typical ballplayer of his day and much more so than Ruth—the Cooper version comes across as neutered and unreal, a kind of Parson Weems’ Washington of baseball. Cooper had a famously omnivorous sex life but you wouldn’t know he had ever experienced lust from his performance here. Similarly, rather than the appealing but unthreatening Wright, Eleanor Gehrig thought she should be played by Barbara Stanwyck or Jean Arthur, actresses closer to her in age who had portrayed mature women with, among other things, active sexual imaginations. Eleanor had led a full (in every sense of the word) life before marrying Gehrig. To portray her as something more than an ingenue would have forced a similar change in the depiction of Gehrig, one that would have tacked the film away from boys’ film cliches. As charming as Wright is in the role, that’s a loss.

Another strange choice by the filmmakers in deviating from the actual Lou and Eleanor story blunts the impact of the tragedy they shared and perhaps mutes its poignance for viewers today. The future Mr. and Mrs. Gehrig met in 1931, first dated in May 1933, and married in September of that year. The movie has them meeting in 1925, getting engaged right after the 1926 World Series (which the Yankees are depicted as winning, though in reality they lost), and marrying in 1933. The film Lou and Eleanor had a 15-year relationship. The real couple’s experience was far more compressed, comprising what Eleanor later referred to as, “six years of towering joy followed by… two years of ruin.” The alteration doesn’t make Gehrig’s passing any less painful to observe, but it changes the dimensions of what the couple suffered. Eleanor later said, “I would not have traded two minutes of the joy and grief with that man for two decades of anything with another,” but her on-screen doppelganger had twice as many installments of two minutes.

Cooper’s performance suffers not only due to his age and awkwardness on the ballfield but due to the filmmakers’ decision to play up Gehrig’s famous reticence and social anxiety. He becomes a gangling Jimmy Stewart character, Mr. Smith Goes to Yankee Stadium. Cooper does not wear this well; for two-thirds of the picture he looks deeply uncomfortable. In 1971, Pauline Kael wrote, “Frank Capra destroyed Gary Cooper’s early sex appeal when he made him childish in Mr. Deeds [populist farce Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936)]; Cooper, one devastatingly lean and charming, the man Tallulah and Marline had swooned over, began to act like an old woman and went on to a long sexless career—fumbling, homey, mealymouthed.” While Kael’s assessment is overbroad—Cooper did have some good performances in the second half of his career—his Gehrig would make a great exhibit for the prosecution. It’s only in the film’s homestretch, when Gehrig becomes ill and he must focus his life down to one final gesture, that Cooper becomes unified with the part. It’s then that one can then easily grasp how a different leading man, one who was a greater ballplayer but a lesser actor, would have torpedoed the film.

We presently living in the United States are enjoying a protracted period of peace, and even when the country has been at war, as was the case with our 20-year adventure in Afghanistan, combat was overseas, limited to the members of a volunteer army (versus the civilian draftees of the Second World War), and for too many out of sight and out of mind. It is only of late that the Americans of this generation have had any real brush with the concept of self-sacrifice. We haven’t exactly passed that test easily, if we have passed it at all. No American society ever has; even the “Greatest Generation” to whom Pride was speaking was far from uniform in its greatness. We are not a people for whom pulling together comes easily. We have to be reminded, exhorted, goaded to get our heads out of our private, parochial sandboxes.

All of the film’s weaknesses fall away in its last few minutes, as Gehrig’s life options rapidly narrow and all that remains is one last chance at on-field greatness, July 4, 1939. The film boils away many of the words Gehrig extemporized that day and rearranges their order so that his most famous words are last. On this one occasion that infidelity to the truth is welcome because it brings intentionality to the moral of Gehrig’s story, one that the actual Gehrig, in his fallible humanity, might have only arrived at accidentally. The truth of Gehrig’s diagnosis was withheld from him and he never fully accepted his fate, whereas the filmic Gehrig knows exactly where he’s headed:

Lou: Go ahead, doc. I’m a man who likes to know his batting average. …Give it to me straight, doc. Am I through with baseball?

Doctor: I’m afraid so.

Lou: Any worse than that? …Is it three strikes, doc?

Doctor: You want it straight?

Lou: Sure, I do. Straight.

Doctor: It’s three strikes.

Lou: Doc, I’ve learned one thing. All the arguing in the world can’t change the decision of the umpire. How much time have I got?

And so to July 4. In Lou Gehrig’s final words we have at least reached the point that Pride of the Yankees is still for us and shows and says things that we still need to hear. The message is one that’s very appropriate for the man who holds the American League record for RBIs in a season: He tells us that even now, on “Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day,” this moment is not about me. It is about how I might affect the people around me. That is a message that transcends baseball and makes a film from 1942 relevant to 2022. All of Cooper’s folksy clumsiness, feigned and unfeigned, doesn’t detract a bit from that sentiment.

This Movie’s WAR: Like Lou Gehrig’s 1936 season, it’s a 9.7.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now