I didn’t want to write this article. As I type this, I’m on vacation. I wanted to sleep in and relax, with my laptop shut down. But John Smoltz won’t let me.

In Friday’s NLCS game, Ranger Suárez allowed two singles over five innings. He hit Juan Soto and didn’t walk anybody. He was charged with two runs, but one was unearned. He faced 20 Padres and retired all but five of them, with two of the five reaching on errors. He struck out three batters. And he threw only 68 pitches, 44 of them for strikes. None of the four batters who reached base on batted balls hit the ball harder than 90.5 mph. He was doing well and showed no sign of fatigue.

Yet he was on the bench for the start of the sixth, relieved by Zach Eflin. It seemed a hasty hook even though the Padres due to lead off the inning, Manny Machado and Brandon Drury, were right-handed hitters against the lefty Suárez. Eflin, followed by José Alvarado and Seranthony Domínguez, closed out the win.

Ken Rosenthal interviewed Phillies manager Rob Thomson about the move. I didn’t hear the interview. (I like Joe Davis, but when he’s got the call, I mute the TV and listen to the ESPN Radio feed when I can. This has nothing to do with Joe Davis.) But I saw it blow up on Twitter, so I pulled up the replay and listened to it. Thomson cited the third-time-through-the-order penalty: The observation that starting pitchers generally do notably worse when facing the opposing lineup a third time.

It prompted this outburst from John Smoltz:

I hate talking about third time through because it’s a moot point. Nobody ever does it. So you can tell me all the numbers you want, third time through. If you’re not trained to know how to pitch, then you’re showing the hitter everything you’ve got in the first two times so you’ve got nothing to give the third time. So elite pitching, take Musgrove, will figure it out. He trains well, he’s big, he’s strong. There should be no issues. But we just don’t give guys the opportunity to do it. So that stat, to me, means absolutely nothing. Because there’s just not enough opportunities to gauge it right.

(The fact that he said this during the bottom of the sixth, when Musgrove was pulled after allowing back-to-back hard-hit doubles [101 and 105 mph exit velocity] while facing the order a third time, is irony lost on him, I’m sure.)

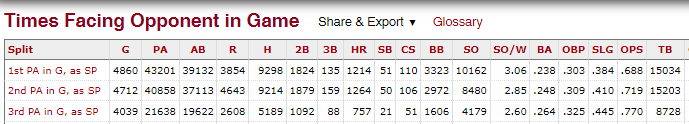

Well, John, sorry, but I’m going to “tell you all the numbers I want.” I’ve written a lot about the third-time-through-the-order (henceforth TTTO) penalty. The way it’s usually portrayed, e.g. on Baseball-Reference, is like this:

Those figures are from this season. As you can see, starting pitchers’ batting average, on-base percentage, and slugging percentage allowed increased each time through the order. Their OPS allowed increased by 31 points the second time through the order and another 51 points the third time. By OPS, it’s like facing 2022 Jesse Winker the first time, 2022 Austin Hays the second time, and 2022 Mark Canha the third time.

However—and this is no knock on Baseball-Reference—there are two important limitations to this representation.

- The first- and second-time-through buckets include all pitchers, not just those who face the order a third time. On June 15, Tyson Miller started for the Rangers against the Astros, faced nine batters, and got only two outs, allowing six runs. That outing appears only in the first-time bucket; his struggles didn’t bring down the second- and third-time figures. Ineffective outings pollute the first- and second-time-through numbers relative to the third, possibly understating the third-time-through penalty.

- Most pitchers don’t make it through the entire opposing lineup a third time. Take Musgrove Friday night. He was pulled after facing the first six batters in the Phillies lineup a third time. That’s a tougher assignment than what he faced the order the first two times, when he got to face the 7-8-9 hitters as well. Failing to isolate lineup position—seeing how pitchers do against exclusively leadoff hitters the first, second, and third times, and no. 2 hitters, no. 3 hitters, etc.—may overstate the third-time-through penalty.

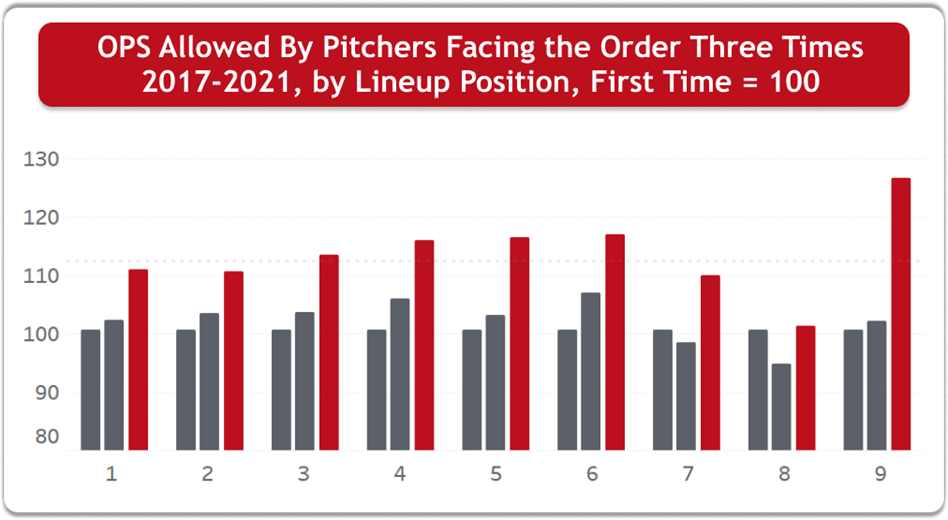

Last year I wrote about this, comparing how starting pitchers do the first, second, and third time through the order, limiting the analysis to only pitchers who faced the opposing lineup three times, and dividing things up by batting order position. Here is a chart from my presentation at this year’s SABR Analytics Conference.

In the five years from 2017 to 2021, starting pitchers who faced leadoff hitters three times allowed a .730 OPS the first time, .742 the second time, and .806 the third time. If you scale the first time through to 100, you get 102 the second time and 110 the third. For number 2 hitters, the progression is .743-.763-.817, which works out to 100-103-110. You get the idea. Every lineup position has a similar pattern. For no. 9 hitters, the third-time penalty is much more severe, because of pinch-hitters for pitchers in National League parks, so take that one with a grain of salt.

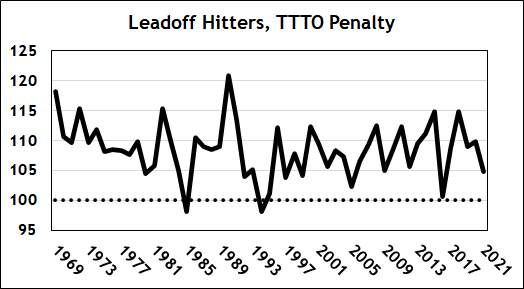

The thing is, this is the modern analytics-driven baseball that Smoltz abhors. So I looked back to see how things have changed over the course of the Divisional Era, starting in 1969. This graph displays the OPS allowed to leadoff hitters the third time through the order, relative to the average of the first two times. Let’s see how much the third-time-through-the-order penalty has exploded since the nerds who never played the game took over front offices.

In 1969, starting pitchers who faced the opposing leadoff hitter three times allowed a .633 OPS the first time, .618 the second time, and .740 the third time. The OPS they allowed the third time—the TTTO penalty—was 18% higher than they allowed the first two times. It was only 5% higher in 2021. If the TTTO penalty is a modern invention, a function of modern players “not trained to know how to pitch,” as Smoltz suggests, we would expect that graph to be upward-sloping, because pitchers today would be less successful facing the opposition a third time than they were decades ago. That’s simply not the case.

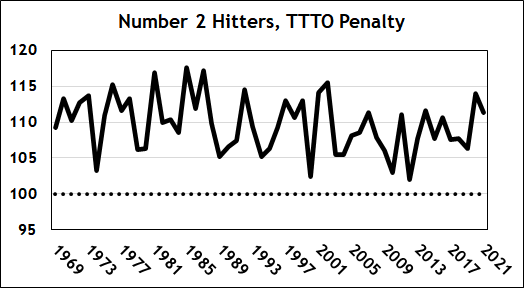

But that’s leadoff hitters. Maybe they’re unusual. Here are no. 2 hitters.

Nope. Nothing to suggest that the TTTO penalty is any worse today than it was 10, 20, 30, 40, or 50 years ago.

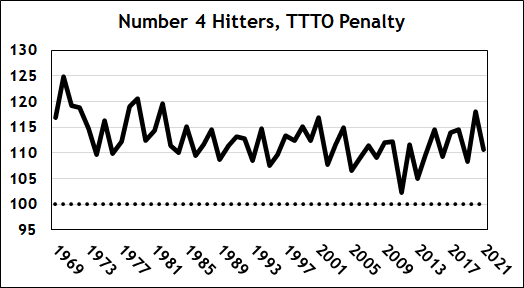

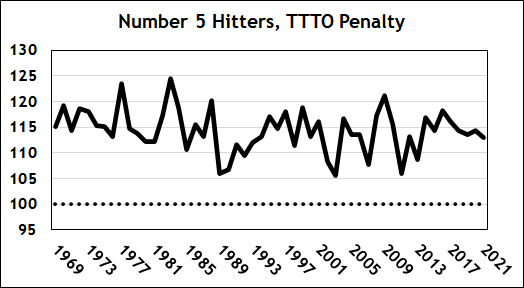

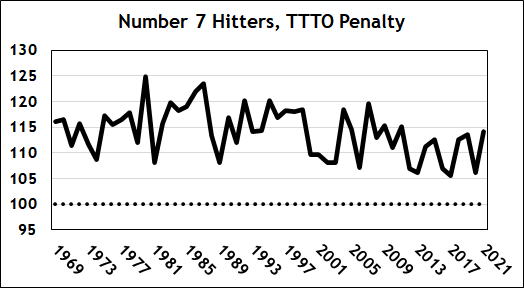

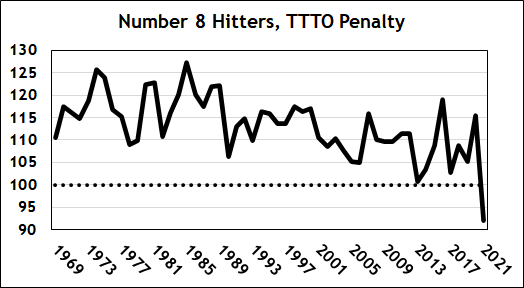

I’m going to present the next six (I’m skipping no. 9 hitters, for the reason cited above) without commentary. The same conclusion holds. The TTTO penalty has existed in its present form, unchanged, for over a half-century. If you’re tired of graphs, scroll past them for the best part of this analysis.

There is no indication that the TTTO penalty is any different now than it was when Smoltz was pitching, or before he was pitching. Pitchers have always done considerably worse the third time through the order than the first two. What’s different—the reason starting pitchers get pulled now—isn’t because they’re less effective or “not trained to know how to pitch.” It’s because, as my BP colleague Russell Carleton has written, relief pitchers are much better now than they were in the past. Not long ago, a fading starting pitcher was better than the available options in the bullpen. That’s not the case anymore.

Now, the best part of this analysis. You could guess where I’m going with this, right?

| John Smoltz, Career OPS Allowed | MLB Average | |||||

| Lineup | # | First | Second | Third | TTTO Penalty | Penalty 2017-21 |

| 1 | 381 | .574 | .667 | .690 | 11.2% | 9.5% |

| 2 | 376 | .682 | .676 | .664 | -2.2% | 8.5% |

| 3 | 370 | .751 | .675 | .867 | 21.5% | 11.1% |

| 4 | 357 | .657 | .708 | .812 | 19.0% | 12.4% |

| 5 | 346 | .641 | .653 | .600 | -7.2% | 14.4% |

| 6 | 337 | .639 | .624 | .675 | 6.9% | 12.7% |

| 7 | 321 | .580 | .552 | .693 | 22.4% | 10.5% |

| 8 | 302 | .427 | .578 | .664 | 32.1% | 3.7% |

These figures are for every game John Smoltz started in which he faced at least one batter the third time through the order: Leadoff hitters 381 times, cleanup hitters 357 times, etc. The TTTO Penalty here is the difference between the OPS allowed the third time compared to the average of the first two times. I bolded the larger Smoltz vs. contemporary TTTO penalty. As you can see, Smoltz was, more often than not, relatively worse facing batters the third time through the order than the pitchers now whom he decries.

Conclusions:

- The TTTO Penalty is not a modern construct. It’s been with us for generations. It’s no worse now than it was in the past.

- That stat, to John Smoltz, may “mean absolutely nothing.” But if he thinks “there aren’t enough opportunities to gauge it right” today, they were when he was pitching. And he was penalized just as much, arguably more, than pitchers today.

- John Smoltz is becoming the Joe Morgan of this generation: Hall of Famer to one generation, caricature to the next. He’s trashing his legacy by becoming the grumpy old man who spouts factually incorrect nonsense regarding concepts and strategies about which he is willfully ignorant. But look at those numbers above. Dude held all but no. 3 and 4 hitters to a sub-.700 OPS all three times he faced them over his career, during one of the top offensive environments in MLB history. He was a hell of a pitcher.

Thanks to Shawn Brody for retrieving millions of lines of data—one line for each plate appearance against every starting pitcher since 1969—for research assistance. Thanks to Derek Rhoads for the cool 2017-21 graph and advice on presenting the data.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now