Baseball is more than just the game played on the field. It can also be the game played on the virtual field. So, Baseball Prospectus is going to write about, review, discuss, whatever the many, many baseball video games released in the last half-century that the genre has even existed.

Baseball Adventure

Developer: Samuel Chiang, Donna K. Woody

Publisher: Loadstar

Platform(s): Commodore 64

Genre: Interactive Fiction

Release Year: 1984

Current Availability: digitally free online, or physically as part of the Loadstar Collection for $15

Why this game?: Well, here’s one you’ve never played before. Hell, here’s one you never even heard of before, because it was included in volume six of Lodestar Magazine, a home computing journal that came packaged with a floppy disk full of free Commodore 64 games. It’s so obscure that Wikipedia doesn’t even include it in its list of baseball video games. This is as deep as the well goes.

How does it play?: As with previous Make-Up Games entry Zork II, Baseball Adventure is an entry in everyone’s favorite genre of video game, the interactive fiction game (or, as they were commonly called at the time, text adventures). The game types out words. You read the words. You type in some words. The computer misunderstands your words. You type the words in again. Think of it like playing Dungeons and Dragons except the DM is a large, fairly intelligent golden retriever.

The structure of the game is to move from one area to the next. You can pick up things, talk to people and give them things, you can wear things. That’s pretty much it. The parser isn’t all that terrible because the gameplay is so rudimentary that there’s no opportunity to confuse it.

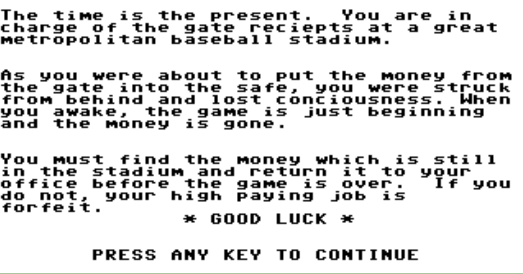

As with most games of the era, the introduction gives you the majority of the story. The goal is to find your stolen money, because you, a very important team employee with your own office, have gone around collecting all the cash from every single gate and walked around with it all before returning to the one safe, where you are mugged. You need that money back. In this baseball game you’re not an athlete or coach. You’re more than that. You’re a middle manager. This is why they make video games, to create worlds to live in.

As a player the game essentially assigns you two tasks. The first: you’ve got to create a map. Even though this is your own workplace, you as the player have to wander around aimlessly; perhaps it was just a really big bump on the head. Admirably, the game does provide the full range of locales: the broadcast booth, the stands, the locker room. You even, if you solve a couple of puzzles, get to wander out into the field itself, mid-game. So that’s neat.

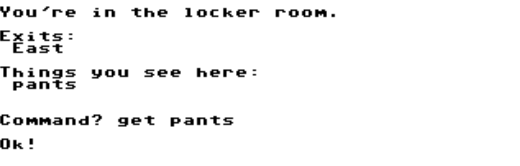

The second task is solving the aforementioned puzzles. The big task is to dress up like a ballplayer so that you can get on the field. The pants and cleats are just lying around, but you also need a cap and a jersey. The cap is being given away by a girl for a contest, which you need a coupon (lying randomly in the bleachers) to win.

The jersey is tougher: You need to sell a spare ticket to a guy outside the stadium, since the game is sold out, so that you can use the money to buy a Coke, who you can give to the Giants’ manager (Frank Robinson) because he’s “always wanted to feel like Joe Greene.” (This is a puzzle that would have landed much better in 1984.)

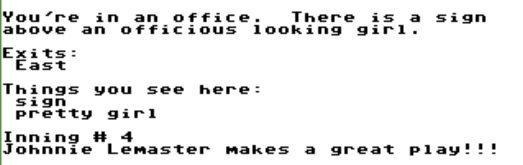

You have to do all this while the game is going on. Every so many turns the game will announce a play from an inning, using real players from the 1983 Giants, clearly the designer’s favorite team. (Howard Cosell, calling the game, comments on how badly they’re beating the hated Dodgers.) Fail to find the money before the ninth inning is over, and you get this screen:

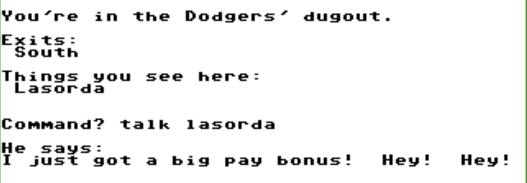

The way you win is to cross the field into the Dodgers dugout and meet beloved manager Tommy Lasorda.

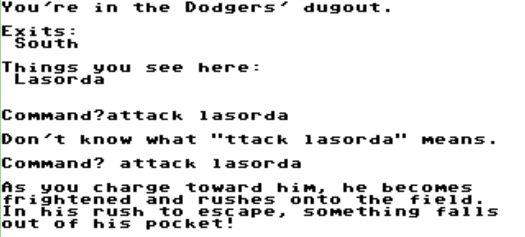

I’m going to confess: I got stuck here. Lasorda’s comment is supposed to be a clue, I suppose, to your missing money, but instead I just felt happy for the guy for having a good turn of luck. Thank god that even though no one has ever played this game, someone has created a walkthrough, because I never would have imagined what the game actually wants you to do:

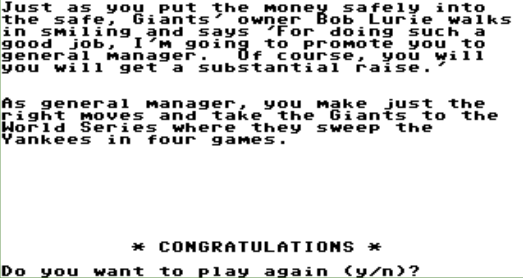

Having attempted assault on an old man with a baseball bat, you pick up the lost ticket money, return to your office, deposit into the safe and win the game.

You do not want to play again.

What this game does better than the rest: We can laugh at how primitive this game is, but there is something legitimately delightful about the interactive fiction genre, even this example, that modern games lack. When you fire up MLB The Show, you can feel that everything it has to offer is laid out. Every possible outcome is planned, calculated in the infinite depths of its code. Hell, it wants you to know exactly what you can do; why go to all the work of making a game and then have a player not know what to do with it? Video games are largely straightforward, honest affairs, giving you exactly what you pay for.

Meanwhile, a text adventure is so incredibly limited in comparison, in terms of what you can do and especially what you can see. Baseball Adventure is painfully barebones, with one-sentence descriptions and few extra details (you can’t even examine the objects you can interact with), and to that extent, it’s disappointing. This is clearly a rushed, free game, a first effort; it is no Zork.

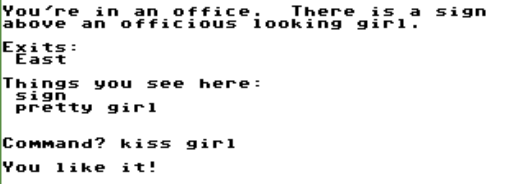

But even so, every text adventures always seem a little greater than they are. There’s no way to tell what the game might let you do, or at least be programmed to respond to. Type in “kill self” in the parser and the game gives you a generic negation: “You can’t do that now.” But then try this:

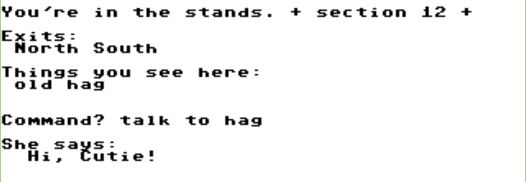

It’s not much—in fact, it’s almost the literal minimum—but the designer thought of you doing this and gives a unique response. The idea of hidden content, always possibly floating just beyond the player’s imagination, makes the world feel full in a way that a graphic depiction of a man in a batter’s box can’t duplicate. In the stands is an old hag. She serves no purpose to the game whatsoever, provides no hints, solves no puzzles. You cannot, alas, kiss her. All she does is this:

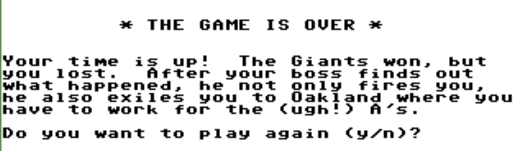

Games are better when they have useless details like this in them, just like baseball is. Something in this dumb game, with its ridiculous premise and random Johnnie LeMaster highlights, feels more lived in, more real than sports games a million times more technologically advanced. Video games are usually better when they’re cheap enough to afford to be weird.

Its industrial impact: One child, one single child, played this game and decided that he, too, was going to work in baseball one day. He made it his life’s goal, drove him through late nights at community college, the first in his family to ever go. And finally, one day, he fulfilled his dream, and became an Accounts Payable Specialist for the California Angels. Dreams do come true.

Baseball Adventure’s Wins Above Replacement: 0.0. This game, for all practical purposes, barely exists. I’m glad it does. The world would be worth less without worthless things.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now