In the Spring of 1947, Jackie Robinson was set to re-break the color barrier in Major League Baseball. Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier reported from Havana, Cuba where Robinson, Roy Campanella, Donald Newcombe, and Roy Partlow were participating in Spring Training that he had learned from an “unimpeachable source”[1] that Jackie would be elevated to the Brooklyn Dodgers from the Montreal Royals before the major league season started. When that moment finally arrived, William G. Nunn, managing editor of the Courier, wrote, “The ‘Iron Curtain’ which has prevented Negroes from participation in major league baseball has been lifted!”[2]

By the end of 1950, Smith, who had been a major voice in the push for integration in major league baseball, was reporting on the declining status of the Negro Leagues. A once-exciting industry in Black communities across the country, many of the remaining teams were folding. “The novelty of seeing Negro players in the majors sent the fans surrying to big league parks in droves and, consequently, Negro baseball suffered to the extreme.” He reported that the Negro National League had folded due to lack of patronage and that practically every Negro team had lost money. It was the worst season in the history of Negro baseball. Major League Baseball had, essentially, killed the only league for everyone they had deemed unworthy. Smith’s assessment of the situation was, “The entire operating pattern of Negro baseball has changed within the past five years. Before the major league doors opened, Negro baseball was strictly on its own and doing fine. There was no competition from organized baseball for Negro players, and there was no competition from the majors for its fans. But up pops Jackie Robinson in a Brooklyn uniform and the entire picture changed. Now Negro baseball must develop talent and sell it to the majors to survive.” [3] The Iron Curtain had not only been lifted, but it had been dropped directly onto the fate of the landscape of Black baseball in America. Though the Negro American League remained, rumors of its funeral grew stronger.

***

“Is Frank Robinson still the first Black manager in Major League Baseball?”

Recently, Major League Baseball made headlines with its announcement that it was recognizing and “elevating” the stats and records of a few Negro Leagues. This announcement was met with applause by a certain segment of the baseball population, and a mix of anger and skepticism by another. The idea that MLB gets to “elevate” anything that is not of itself is a problem that’s been discussed at great length, but a thing that has caught my attention is what this means for existing history, for existing records. I’ve noticed some seem to think that this integration of records will allow MLB to absorb, so to speak, the legacy of the Negro Leagues and re-write history.

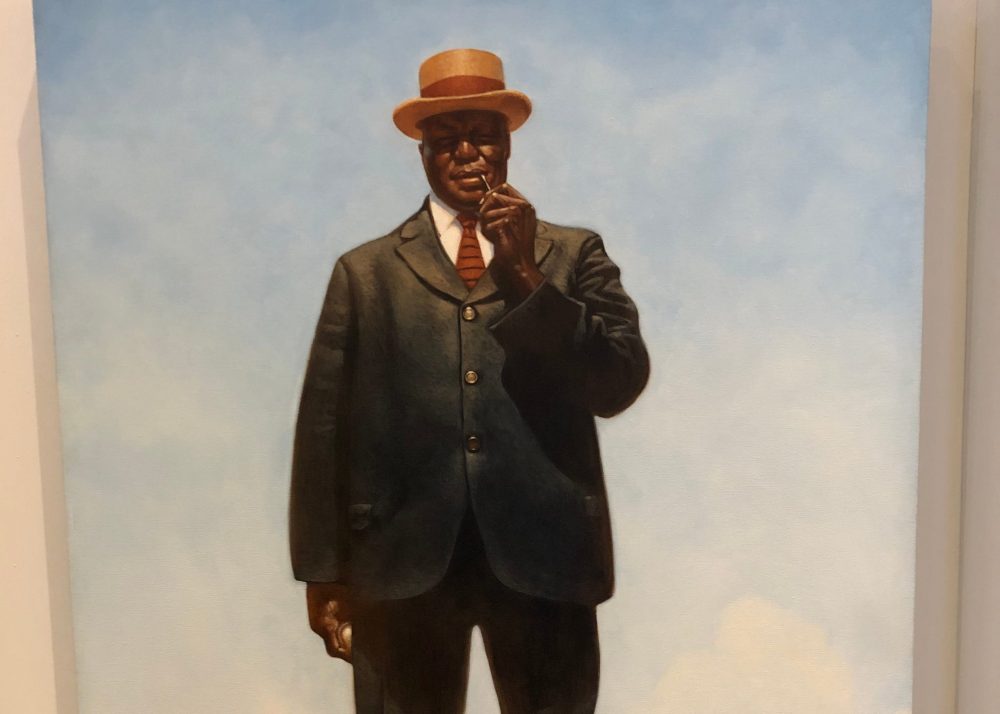

In 1920 when the Negro National League was formed, Black Americans could fight and die for this country but they had very few freedoms, could not vote, were not considered worthy of playing what was deemed professional baseball. When Andrew “Rube” Foster had the idea to organize Black baseball, he wanted to do so for the benefit of not only the players, but the sport itself. Black Americans had been playing the sport since its inception. Octavius Catto used baseball as a way to fight for civil rights; he was murdered while on his way to defend Black American men and their right to vote in 1871. It’s important to remember the circumstances under which the Negro National League was formed. Negro league baseball capitalized off the segregation and discrimination of not only society, but more specifically the majors. It’s important that, despite all of their acknowledgement and recognition—or perhaps through it—MLB has sidestepped the fact that they created the environment that necessitated that which they’ve now subjugated.

The Negro Leagues and their history has been relegated to the margins for a century. Separate and unequal for 100 years. An intentional and deliberate action on the part of traditional media and, by extension MLB. Their statistics and records didn’t matter much to anyone outside of it, but particularly anyone affiliated with “organized baseball”. They were seen as amateur, as a sideshow, as less than. That’s not something that should be forgotten.

Today, Branch Rickey’s “great experiment” is no longer an experiment. The last major league team integrated in 1959. There’s no agreement as to whether the phrasing was intentional or accidental. We don’t yet know what the plan is to “elevate” the records, but the cutoff for inclusion is 1950. I once read that history is the lies of the victors. With one press release, MLB was once again positioning itself to drop their iron curtain on the Negro leagues.

The merging of records brings about the possibility of continuing a longstanding tradition of sanitizing the past. From Martin Luther King, Jr. to Jackie Robinson, and any other Black baseball icon who has passed away, the blemishes of racism are often painted over with a kind of warped nostalgia. Instead of attempting to reshape history, now is the perfect opportunity to understand the Negro leagues were a response to not being included, not a request to be included.

While it is my hope that the idea is keeping them separate, but acknowledging they’re equal, history shows us that, in most cases, no one actually learns from it.

Yes, Frank Robinson is still the first Black manager in Major League Baseball.

[1] Wendell Smith, The Sports Beat, Pittsburgh Courier, p. 14, April 05, 1947. [Print]

[2] William G. Nunn, “Let’s Take In Stride: Courier Managing Editor Urges Negro Fans to Sponsor Good Conduct,” Pittsburgh Courier, p. 18, April 19, 1947. [Print]

[3] Wendell Smith, The Sports Beat, Pittsburgh Courier, p. 14, December 16, 1950. [Print]

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now